November 9th, 2025

Confession time: I have a hell of a collection of back hair, belly hair, chest hair, even butt hair and ear hair. Fo’ real.

I know, I know, a man of my age does not age well, as “things” begin to grow from every orifice and heretofore unknown location, but so why then do we have to write about it…sorry, my apologies. There is an honest purpose here.

You, the lone, long-suffering sole reader of this blog, are probably already thinking to yourself “Good Lord, this guy has finally gone off the deep end with this TMI shock jock shtick. ” And were we actually talking about real body hair from my own voluptuous, idyllic form, you would be correct. However, as racy or as disgusting as this may sound, the fact is that I do have a pretty cool record-setting collection of all the aforementioned clumps of hair, but they are not from my own body.

Again and now even more so, whoever is left reading here at this point is gagging, and wondering what happened to the erudite intellectual who used to occupy this lonely outpost of fascination. Well, the bad news is I yet remain under the mal-influence of one Bill Heavey, the also-lonely humor writer of the once-wonderful magazine known as Field & Stream, now digitally un-dead and unknown to Americans under the age of sixty.

The good news is that I am not talking about human hair here, but rather the hair, or fur, of the many deer I have shot arrows at over the past five decades. This is true. I am not lying.

See, I fancied myself an archer at a young age, and so I got somewhere (probably at the kind of now-gone country auction that elderly collectors dream about and salivate over) a cheap recurve bow and a motley assortment of mis-matched arrows and dull broadheads, and set out to bag a deer.

Yes, I practiced, for years, as only the uninitiated and un-groomed and un-mentored can practice. Which meant that on Tuesdays and Fridays my archery “form” aligned well enough that I could hit the broad side of a barn, which were plenty, large, bright red, and quite broad where I grew up. And on all other days of the week my arrows sailed off into the wild blue yonder, to sit hidden in the fallow weeds and maybe puncture a neighbor’s tractor tire the following spring. Or maybe eventually catch my eye and be re-purposed as an arrow, more defunct stick than game-getter at that late point, but available and at-hand, and so useful nonetheless.

As a young man, I shot at deer from the ground and from neighbor’s hillbilly blinds, AKA rickety wooden death traps in today’s more refined hunting circles. My woodcraft was then and remains now unbeatable, and I am not lying or exaggerating when I tell you that I could stalk within feet of a dumbfounded deer, and let fly. Only to watch my arrow clip hair from the aforementioned areas and parts of the deer’s external anatomy, time and time again.

Bill Heavey would tell you, had he been as cool as me as a kid himself, that the deer died of laughter from the ridiculousness of the experience. But no, my deer did not die of anything. Not from shock, not from surprise, not from overwhelming mockery of the incompetent human mere feet away, and not an arrow in the heart. No, my deer stood stock still, with grass or acorns or corn hanging out of their slack jaw, staring at me in disbelief. Some even provided me with two shots.

I could have died from the shame of it all.

This routine of Bad-Indian-Sucky-Bow went on for decades, even as I graduated to used but working Fred Bear Kodiak recurves and then to custom “stick” bows. My prize and pride is a beautiful reflex-deflex longbow made by none other than Mike Fedora, the dean of modern traditional archery in America. Back in 2000, Jack Keith and I traveled from Harrisburg to the Eastern Traditional Archery Rendezvous, then at Denton Hill in Potter County (home of many more bears than people), where we connected with Jack’s dear friend John Harding, and where I was introduced to Mike Fedora.

At ETAR, Fedora traced my bow-holding hand, did some phrenology-like measurements of my various body parts, and pronounced that the bow of my dreams would be ready within a few months. And no sh*t, Mike Fedora did produce a beautiful bow that was like an extension of my soul. I could then and still can shoot that thing into bullseyes all day long. At archery targets, me and that custom bow are deadly.

At deer, I still drop the ball. No can hit. Must be nerves, which are steely when I am hunting with a rifle. And so my arrows continue to clip bits of hair from all over deer bodies all over Upstate New York and Upstate Pennsylvania.

I am telling you, my collection of these bits and clumps of hair is large and legendary. If nothing else, no human being alive has missed so many deer at so short a distance for so long as I have. A living, walking, malfunctioning Guiness Book of World Records I may be in this regard, around these parts it is nothing to brag about. Rather, I inspire pity from even little kids dressed in camo who have already arrowed several Pope & Young bucks by the age of seven.

In the not too distant past, someone with my pathetic archery hunting skill would have perished from starvation long before amassing even the beginning of such a fine and rare collection.

And yet, I have discovered hope, salvation for my pathetic-ness and hopeless skill-less-ness. As much as I hate to admit it, I, a traditional archery snob who mocked bows with “training wheels” (compound bows) and belittled “bow-guns” (crossbows) as un-sporting arms that no worthy deer would allow itself to be taken by, I have finally fallen to the siren song of the modern crossbow. Or, to be honest, the cross-gun that shoots a short arrow like some kind of James Bond super-weapon.

Despairing of my ineffectiveness at archery hunting, and desiring to finally carve some notches in something to prove my prowess as a traditional hunter before I expire, I went and bought a Ravin R10X crossbow. It came highly recommended by contractor Ken Pick of Renovo, PA, whose son aced a very nice mountain ten point with one two weeks ago at the distance of 87 yards.

I can barely hit a deer with a modern centerfire rifle at 87 yards, so when I saw the photos of the young chap and his buck and his James Bond cross-bow-gun, I decided if I could not beat them, I had to join them. And join them I did, by buying said Ravin R10X at Baker’s Archery in Halifax, PA. Vindication and verification and all related cations came at me real fast as soon as I took that scary-ass contraption afield.

This is no lie and no exaggeration: Ten minutes after I took a little mosey to a spot where I had not hunted before, but where I thought deer had to be (this is the woodcrafty Josh), I had whacked an anterlessless deer. I had only put the scope reticle on the spot where I thought the arrow would hit the deer, and before I even pulled the trigger a loud THWACK resounded in the woods.

The deer ran twenty yards and died of fright, with a gigantic hole coursing through its body where I must have aimed but do not remember doing so, due to my own shock at having actually killed something with a stick and a string.

Life is full of surprises. Don’t deprive yourself of these dangerous-as-hell you’ll-shoot-yer-eye-out-kid bow-gun contraptions. Dude, they are cool and totally worth it.

Take my experienced word for it.

The trophy of my dreams: A yearling button buck taken with a James Bond super weapon on a ground stalk

A young man who was mentored in traditional archery, with good form, at ETAR 2020 at Ski Sawmill

People’s trail cameras are literally everywhere. This was sent to me as I was preparing to ask this kind young man to help me drag the deer fifty feet to the gravel road

No joke about it, my friend and archery and life mentor, Jack Keith, was the real deal in everything, and I miss him every day.

People who subsist on archery can’t afford to write silly essays about sucking at archery

Traditional archery legend Fred Asbell showing how to correctly hold the bow while hunting. Fred took all kinds of animals all around the world with traditional archery tackle

A young man with even better archery form at ETAR 2022

January 2nd, 2024

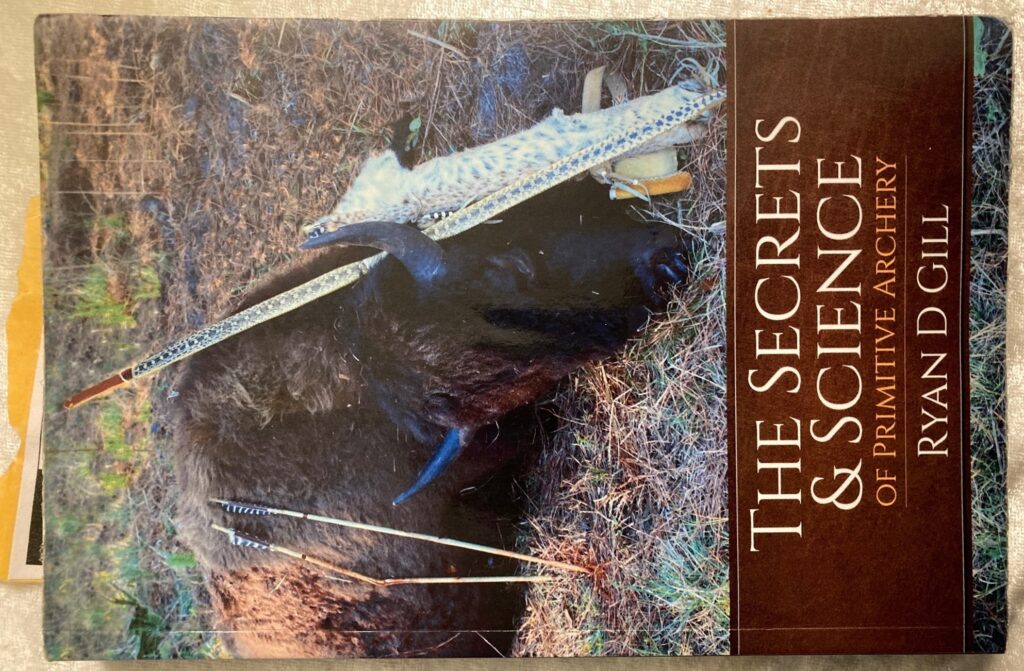

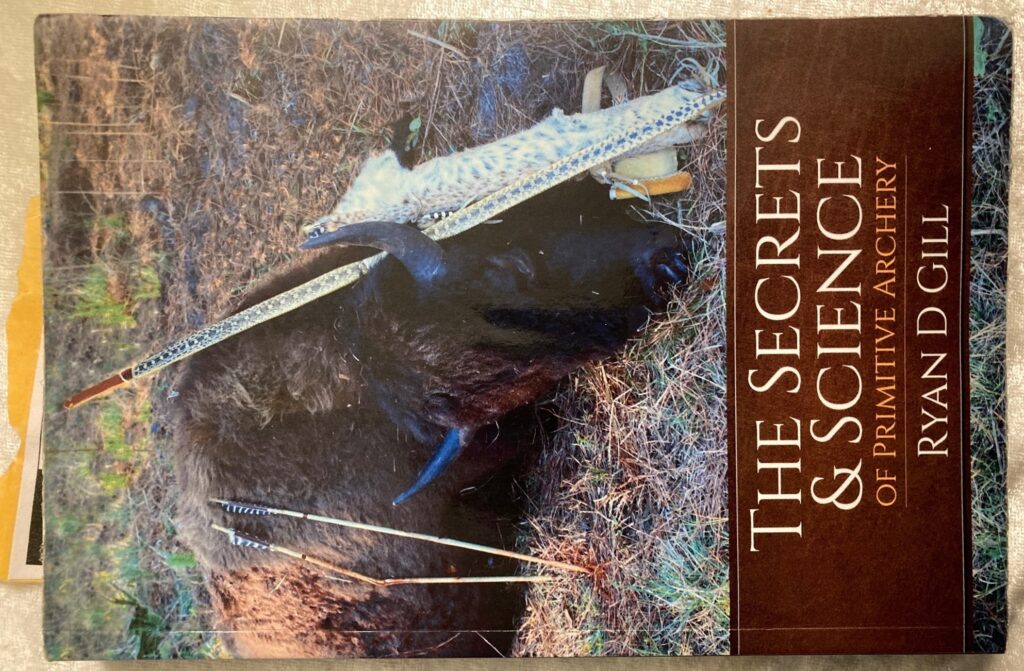

Ryan Gill’s book, The Secrets & Science of Primitive Archery, is a must-have for all stick bow hunters. You cannot find your way in the dark without a light, and this book is the illumination every traditional and self-bow hunter needs. I don’t care how long you have been hunting with your Osage orange self-bow or even a traditional bow by a small maker. If you hunt with something that does not have training wheels, then you need this book.

I must admit that I am almost ashamed it has taken me over a YEAR to review this book. Actually almost two years. Author Ryan Gill deserves much better treatment for all the hard work he put into this book. What can I say, Ryan. America has had a lot of ups and downs since 2021, and for political watchers and commenters like me, practically every day has felt like an all-hands-on-deck. All the political stuff has taken up the blog space. I am sorry, buddy. Hopefully I finally give you and the excellent book your due here.

As a traditional archery hunter since I was about fourteen, I have been enamored of bows made of a simple stick and a string. When us kids made our own bows out of saplings we cut in our woods (fifty years ago…), we would tie on a piece of baling twine and shoot arrows made of tree branches, goldenrod, whatever we could get our hands on, and practice with what we had. As the years went past, some of us were gifted compound bows, and others got simple recurves. I got a recurve, and some pretty sorry secondhand Easton aluminum arrows, to which I attached basic Bear broadheads.

If I had a nickel for every deer I collected hair from, I would have enough to buy a malted milkshake at the Lewisburg Freeze, which was fifty cents way back when, and costs five bucks now. That is to say, I never killed a deer with a bow, but missing didn’t stop me from trying.

Fast forward and I had my own kids, all of whom enjoyed shooting little fiberglass kid bows. When the boy attained the age of about seven, he demanded a “real bow,” and so off to the Eastern Traditional Archery Rendezvous we went. There we located a nice faux curly maple kid recurve with about 20 pounds of pull. Enough to skewer a squirrel or ball up a bunny in the back yard, which the boy kept after. Many years later we would go back to ETAR to get his real Big Boy bow, a reflex-deflex by the Kilted Bowyer. At 43 pounds pull weight at 26 inches, this is a true hunting machine, pretty, yes, but in all the clean simplicity a true bow should have.

But in between the little boy bows and the last big boy bow there were a lot of experiments over the years. Saplings cut, strings attached, arrows made, trials run. Like I did when I was a kid fascinated with the basic but powerful physics of archery. And this is where Ryan Gill’s fascinating book enters the picture.

Ryan Gill came to our attention by his YouTube videos. Because we were naturally looking for information about what we were doing right and doing wrong. Ryan doesn’t just cut saplings, attach a string, and shoot some crappy home made arrows. Au contraire! Ryan makes all kinds of powerful self-bows from all kinds of different woods, including Osage orange, hickory, black locust, and others, that will kill deer, bear, wild hogs, and even huge bison. And then Ryan strings the bows with real animal gut. And then he makes real cane arrows, tipped with real flint and chert heads that he himself knapped. Talking the real deal here. And through it all in his videos and his book, Ryan explains how primitive archery really worked tens of thousands of years ago, and how it can work really well for us today.

I learned a lot from this book.

Because I am a numbers guy, Ryan’s statistical analysis of his different bows, using different strings (animal and plant fiber), using different arrow shafts (river cane, wood) etc, really speaks to me. He does a great job of tabulating his data, which, when all his testing is said and done, tells us exactly where to go: Osage orange bow stave that is dried daily, using either a modern bow string or an animal gut string, and shooting properly made river cane shafts fletched with goose feathers and tipped with the proper and surprisingly small stone arrowhead, that go at least 130 feet per second, with 150 fps or better being the best and most likely to catch an unaware deer standing flat-footed.

If you are at all a traditional or aspiring primitive archery person, you need this book. This is a must-have resource that you will find nowhere else. It has an incredible amount of fascinating and directly applicable how-to information to every step and facet of primitive and traditional archery, as well as the historic and anthropological background to how primitive archery evolved. I read it twice before I felt qualified to write about it here, and I highly recommend it.