Posts Tagged → land

Trump Great American Outdoors Act hits Conservation Home Run

Conservation is where I have spent my entire career, and it is where my heart resides day in and day out. So it is with great happiness that I see President Trump sign into law the Great American Outdoor Act, which will do the nuts and bolts environmental protection America needs, without the regulation that America does not need.

The fact that so many political appointees within the Trump Administration were cheerleaders for the GAOA says a lot about the political tenor there. So many people accuse the Trump Administration of being some kind of radical “right wing” blah blah, and the fact is that the entire administration is loaded with middle-of-the-road professionals, who hold a mix of political, philosophical, and ideological views. In past Republican administrations, there were plenty of appointees who would have blocked GAOA, or held it up. GAOA is a signature achievement for President Donald Trump, and it is a huge win for Americans.

GAOA fully funds the Land and Water Conservation Fund for the first time in a zillion years. It provides adequate funding for federal and state parks infrastructure updates, operations, and maintenance costs. These are the costs that are always deferred in every administration. It is a subject I wrote my master’s thesis on at Vanderbilt University, and it is a subject that has never gone away, until now: Federal recreational infrastructure has been woefully underfunded for decades. Many state parks across America are in even worse shape than that National Parks.

For example, in 2016 my teenage daughter and I hiked half of the Northville Placid Trail, which runs through the Adirondacks. At the end of our ninth day, as we waited out a looming thunderstorm in a rustic but comfortable lean-to deep inside designated wilderness, on a hike in which we had encountered only a few other people, my daughter sat looking at her dead iPhone. Like Gollum looking at The One Ring, only my daughter looked more disgusted and glum than happily mesmerized.

“I have to get out of here. I want to talk to my friends. I want to know what is happening in the world. We need to go,” she said, and picked up her backpack, jumped down onto the grass, then shouldered her backpack.

Oh, I tried to persuade her to spend the night and stay out of that coming downpour. But she would have nothing of it, and she set off by her own teenage self, going somewhere, maybe anywhere, and I was standing there watching her pick her way into the forest.

Hours later we emerged at Moose River Plains, what maps describe as a rustic New York State recreational area tucked away deep in the Adirondack wilderness. What we found was a boarded up main building, boarded up out buildings, no gate, and no official staff. Instead, a bunch of locals who regularly camp there had taken over the official duties of park rangers. Even the land line phone system was not working. It was a very kind local who drove us, each drenched to the bone and with sodden packs, to the closest village, where we could contact our driver and get back to our own vehicle parked at a Baptist church in Northville, so my daughter could get home and talk with a zillion friends simultaneously.

Turned out that Moose River Plains was victim to a New York State budget that prioritized funding illegal aliens, but not state parks.

The Moose River Plains experience was worse than our visit the year before to Saratoga National Battlefield, by far. But seeing Saratoga National Battlefield, where the brave fight for American freedom and independence was won, in such terrible disrepair and threadbare means, was frankly shocking. One expects the National Park Service to do so much better. And when we spoke with a park ranger there, she was clearly hurt, personally, as she explained the money constraints that park faced. NPS just could not get the job done.

All of this is to say that finally, money floweth in the right direction. The need out there for public infrastructure is almost beyond compute. It is about time that America invested in our national parks and forests, state parks and forests, local and county parks, and the myriad other adjunct little recreational areas, like Moose River Plains, so that Americans might enjoy our public outdoors.

And about that public outdoors thing: Public land is a public good. Public land is one of the very few things that government does pretty well. And even when government land managers fail, the outcome is almost always simple neglect; the land always remains, the wildlife habitat remains. Which means the opportunity for recreation, hunting, fishing, hiking, camping etc remains. It is not a real material loss when land managers screw up or there isn’t enough money to operate the park entrance gate house; just missed opportunities, and putting a frowny face on a public symbol.

Congratulations to President Trump for pushing hard for GAOA, for hiring the right kind of land management staff and public lands leaders, and for caring about our public lands at all levels – local, state, and federal. Trump understands Americans, and he knows how much we care about our public lands, our state parks. And he knows how important it is to constantly invest in those places, so that they don’t fall into disreputable disrepair, like Moose River Plains had fallen.

One of the parts of GAOA that is so very appealing to me is the public land acquisition funding. As development never sleeps, what were nice public spots to hunt or hike in suddenly find themselves cut off or surrounded or overrun by development. It is nice that states and local governments will finally be able to buy that ‘Mabel’s Farm’ the community always wanted, and could not afford.

There is going to be a lot of Mabel’s Farms bought with GAOA money in the next few years, a lot of Nature conserved, and a lot of communities and hunting places protected, as a result. Thank you, President Trump, conservationists everywhere appreciate your leadership on this important policy area.

With special people at Yosemite. Can we imagine America without Yosemite? It takes money to protect these special places.

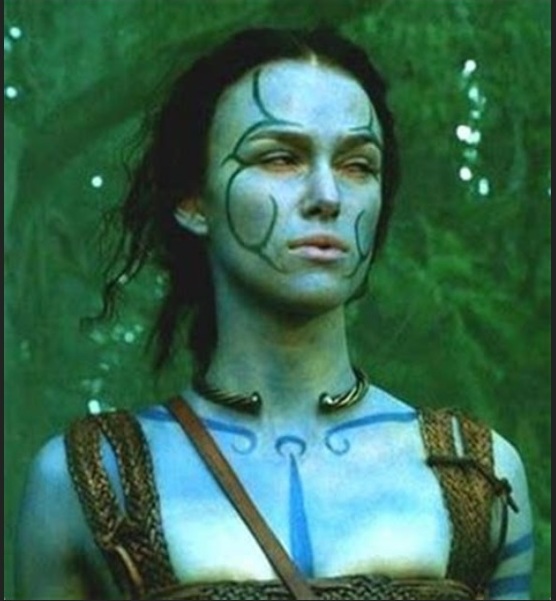

My daughter at the unhappy lean-to. But still, it was a functional, dry lean-to next to clean water in the middle of ADKs wilderness

Our friends Mark and Amanda at Leonard Harrison State Park, overlooking the Pennsylvania Grand Canyon

My daughter at Cedar Lakes, a special moment that spurred her on to teach wilderness backpacking to kids. Now she can’t wait to reach the area of no cell reception

Purple woad. Or why hunting leases

Leasing land to hunt on is a big thing these days, and there is no sign of the phenomenon decreasing. Most of it is about deer and turkey hunting.

Hunting leases have been popular for a long time in states with little public land, like Texas, but the practice is now spreading to remote areas like suburban farms around Philadelphia and Maryland. So high is the demand for quality hunting land, and for just finding a place to hunt without being bothered, and so limited is the resource becoming, that leasing is a natural step for many landowners who want to get some extra income to pay their rent or fief to the government (property taxes aka build-a-union-teacher’s-public-pension-fund).

Having been approached about leasing land I own and manage, it is something I considered and then rejected. If a landowner at all personally enjoys their own land themselves, enjoys their privacy there, enjoys the health of their land, then leasing is not for you. Bear in mind that leasing also carries some legal liability risk, and so you have to carry sufficient insurance to cover any lawsuits that might begin on your land.

Nonetheless, some private land is being leased, having been posted before that. And the reason that so many land owners are overcoming the same hurdles that I myself went through when considering land leasing, is that in some cases the money is high enough. Enough people want badly enough to have their own place that they can hunt on exclusively, that they are willing to pay real money.

Makes you wonder what kind of population pressures and open land decreases America has seen over the past fifty years to lead to this kind of change in land use. Makes me think of one anecdotal experience.

On the Sunday of Memorial Day Weekend of 2007, I drove up to Pine Creek to dig the footers for our barn. All the way up I shared the road, in both directions, with two motorcyclists headed in my same direction. That is it. In addition to my pickup, a grand total of two vehicles out for a Sunday drive in the country were on Route 44 and Rt 414.

Fast forward 13 years and my gosh, Pine Creek Valley has nonstop traffic in both directions at all hours. It does not matter what the time of day or night is, there are vehicles going in both directions. And not just oversize pickup trucks possibly associated with the gas drilling occurring around the area. Little tiny dinky tin can cars are going up and down the valley, too. There are literally people everywhere here now, in what had been the most remote, undeveloped, quietest corner of rural Pennsylvania. Even if you go bear hunting on some sidehill in the middle of nowhere up in Pine Creek Valley, you will encounter another hunting gang or two. Which for bear hunting is actually a good thing, but the point being that there are people everywhere everywhere everywhere in rural Pennsylvania.

OK, here is another brief anecdote. Ladies, skip ahead to the next paragraph. About ten years ago I was fishing on the north end of the Chesapeake Bay. When I was finished for the day, I drove back north toward home. At one point I had an urge to pee, so I began looking for a place I could pull off and pull out, without offending anyone. Yes, I have my modest moments. And you know what? The entire region between The Chesapeake Bay’s northern shores and the Pennsylvania Mason-Dixon Line, is completely developed. Like wall-to-wall one-two-three-acre residential lots on every inch of land surface. At the one place that finally looked like I was finally going to get some relief, I stepped out of the car and was immediately met with a parade of Mini Coopers and Priuses driving by on the gravel road to their wooded home lots. There was literally people everywhere, in every corner, in every place.

So what happened here?

There are more people and there is more land development, both of which leading to less nice land to hunt, fewer big private spaces for people to call their own, and so that which does exist is in much higher demand.

Enter Pennsylvania’s new No Trespassing law. AKA the “purple paint” law.

Why was this new law even needed? Because the disenfranchised, enslaved Scots-Irish refugees who originally settled the Pennsylvania frontier by dint of gumption, bravery, and hard work had a natural opposition to the notions and forms of European aristocracy that had driven them here. Such as large pieces of private land being closed off to hunting and fishing. And so these Scots-Irish settlers developed an Indian-like culture of openly flouting the marked boundaries of private properties. Especially when they hunted.

And this culture of ignoring No Trespassing signs carries forth to this very day.

Except that now it is 2020, not 1820, and there are more damned people on the landscape and a hell of a lot less land for those people to roam about on. Nice large pieces of truly private land are becoming something of a rarity in a lot of places. Heck, even the once-rural Poconos is now just an aluminum siding and brick suburb of Joizy.

So in response to our collision of frontier culture with ever more valuable privacy rights, Pennsylvania now has a new purple paint law. If you see purple paint on a tree, it is the equivalent of a No Trespassing sign. And if you do trespass and you get caught, the penalties are much tougher and more expensive than they were just a few months ago.

And you know what the real irony is of this purple paint stay-the-hell-out boundary thing? It is a lot like the blue woad that the Celtic ancestors of the Scots and Irish used to paint their bodies with before entering into battle. Except it is now the landowner who has painted himself in war paint.

Isn’t life funny.

Conservation vs Environmentalism

After decades of environmentalism, many Americans are burnt out on the movement’s constant sky-is-falling hype and never-ending Defcon 5 emergency messaging. Environmentalists’ craving for full control of our every motion and breath understandably scares the daylights out of normal Americans.

Though environmentalism is sold as a take-it-or-leave-it proposition by its proponents, the truth is that it represents an unnecessarily confrontational and expensive approach to environmental and public health, with misplaced priorities and unmeasurable outcomes.

Simply put, Environmentalism is the over-reliance upon government coercive force, command-and-control, one-size-fits-all sledgehammer policies to problems that might require a screwdriver, if needing anything at all.

The premise behind environmentalism is that mere daily acts of human existence are pitted against a static natural environment that must be defended at all costs, in the face of change being this planet’s biggest constant. Un-anointed humans are vermin in environmentalism.

Oh, sure, pollution and environmental destruction from human activity do exist: Over-fishing of the shared oceans is resulting in catastrophic population reductions of the most valuable fish (tuna, sharks, some salmon). Low-density residential development and warehousing goes up on our flattest, best, most fertile farmlands while national food security is an ever growing concern. Where will we grow our own clean food, if not on our best farmland closest to our largest population centers? Preventing water pollution is a constant effort. And certain chemicals were not vetted properly, with the burden of proof placed on the hapless citizenry before they were discovered to pose unacceptable health risks.

Republican President Richard Nixon said it best: “What a strange creature is man, that he fouls his own nest.” This is just being honest, though the very people most radicalized about environmental issues are also and equally fouling our collective nest with their own reliance on cars, iPhones, and hip clothing. They aren’t special. In fact the most “special” among them have their own personal jets and huge cars and boats with daily carbon footprints the size of small towns. Hypocrisy has a way of passively degrading and delegitimizing people, and that has happened with environmentalism’s biggest messengers, like Al Gore, Leon DiCaprio, et al.

Each of the real environmental health issues we face can and will be tackled with all of our best Yankee ingenuity. Not every day needs to be the summer of 1968, and not every environmental issue is Love Canal or will result in Planet Earth’s extinction if we don’t implement drastic policies right now. At its worst, environmentalism is virtue signaling and fake moral outrage.

A more measured, more adult approach is needed.

America is hopefully about to see a blossoming of conservation. Aldo Leopold called it a “conservation ethic,” where a sense of stewardship results in concrete steps to protect natural resources for future generations of Americans.

Yet, conservation is mostly boring as hell. It lacks the screaming and yelling, the gnashing of teeth, the drama of environmentalism. It lacks the big demands for dramatic lifestyle changes and income redistribution that falsely substitute for self-examination, introspection, personal change.

By relying on market forces and free choices by people inside those markets, conservation empowers the very people environmentalists despise. Conservation involves a lot of actual heavy lifting among and by people who care: Raising private money and judiciously spending public taxpayer money on carefully ranked projects that are of both great symbolic and tangible meaning to the citizens.

It involves natural resource management and planning, which environmentalists decry while using more than their fair share of those same resources.

While land conservation is the best example of conservation, there are plenty of successful, subtle, fish and wildlife management models and even agricultural management models (with pesticides, insecticides, herbicides, fertilizer inputs). Back in 2002, I co-founded the Conestoga River Nutrient Management Project in Lancaster County, to use market forces to address waterway sedimentation finding its way to the Chesapeake Bay.

These are definitely not sexy policies. Conservation does not involve the glitzy rock star concerts, Hollywood celebrity interventions, and spectacular claims of imminent world-end that environmentalism has going for it.

Conservation is for adults, and now the adults are in charge. Hopefully the adults can teach the children to eat their vegetables, so to speak.

The Sad Situation in Standing Rock

A person must be cold blooded to not at least feel sad for the Standing Rock folks.

This is a group of ancient people who have watched their culture, lifestyle, property, and land heritage melt away under the weight of newer tribes. They really don’t have much left, and now a pipeline threatens to take away even more.

The Dakota Access pipeline is important, heck, all the new pipelines are important because energy independence is critical to American political independence. The more America can rely on domestic energy, the less we need foreign sources of energy. The less we depend on those foreign sources, the freer we are to make tough but necessary decisions about domestic and foreign policy.

What saddens me is the win-lose situation in Standing Rock. The pipeline is presented as a take-it-or-leave-it outcome. Surely there is some other way to resolve this, other than ramming it through. After all, that has been a hallmark of the failed Obama administration and their legislative allies on so many other policy fronts, ramming decisions down everyone’s throats. It is a negative way to run government. It unnecessarily creates winners and losers.

Creating winners and losers is a recipe for serious problems down the road. Resentment runs deep. Grudges are created. Losses are forever mourned.

I know from experience that the Standing Rock situation presents us with an opportunity to create winners and winners.

How well do I recall sitting in a conference room at my office in downtown Harrisburg in 2001. Gathered around the table were representatives from Audubon, Sierra Club, recreational ATV riders, hunters, trail hikers, and the timber industry.

I had successfully negotiated the purchase of a privately owned 12,500-acre inholding in the huge Sproul State Forest from the Litke family. Donna Litke was a neat Pennsylvanian who loved her family’s rugged wilderness land in the northcentral country, but who also had a fiduciary commitment to her family to get the best financial results possible from any purchase. Her private land would become public land after we acquired it.

But Everyone wanted the whole property for their own interests. Or they wanted to block their political opponents from getting something out of it.

After hearing all the crabbing from all sides, left and right, environmental groups and industry, I decided that we would not acquire the property unless everyone got something out of the deal. Everyone needed to share in the success, or else we were not going to see the deal close.

So the day we sat down with a map of the Litke land, and began to discuss where certain activities could or would best take place, was the day we began to get to a win-win outcome. In the end every interest group got something out of the acquisition. Audubon and Sierra Club saw certain sensitive lands there set aside as natural and wild areas, where logging, road building, and gas drilling would not occur. We created a 1,400-acre ATV riding area on reclaimed and unreclaimed coal mining land there, too, the first one on public land in Pennsylvania, which today has generated substantial economic activity in ultra-rural Beech Creek.

Much of the Litke forest was set aside as “plain vanilla” State Forest, where people can walk, hike, camp, hunt, trap, fish, and cut timber. The streamside railway that came with it became an important rail-trail, drawing tourists (and their dollars) from far and wide.

And I did not learn how to do this cold. Rather, in 1995 to 1996, I had successfully used the same approach in the Middle East Peace Process agricultural projects in Jordan, Israel, and the West Bank when I was at US EPA, representing our agency in the diplomatic process.

Boy, you talk about competing interests! There was no shortage there, but in the end I was dubbed “Little Kissinger” for the sidebar negotiations I created, which got the overall projects back on track. Winners and winners.

My hope is Standing Rock will provoke the best in us. Barack Hussein Obama did nothing to help the folks there, until two weeks ago he made a purely political and symbolic decision against the pipeline. Obama has always been about winners and losers, heck he enjoys creating losers, so who can be surprised by his action here. Like everywhere else over his eight-year tenure, Obama squandered an opportunity to facilitate competing interests find common ground.

And that is what needs to happen at Standing Rock: Common ground.

Aren’t there potential solutions to this standoff that are win-win? I can think of three or four potential solutions that would probably be acceptable to the main parties.

We have a new president who understands the concept and importance of win-win outcomes. Hopefully President Trump appoints a solid and good-faith negotiator to resolve the head-on collision at Standing Rock, for everyone’s benefit.

Winners and winners.

Our dear friend, Don Heckman

Don Heckman needs little introduction in the sporting circles of Pennsylvania and the East Coast.

A founding member and long time leader of the Pennsylvania chapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation, Don’s cheerful, generous and kind personality and locomotive work ethic helped re-establish wild turkeys to Pennsylvania in the 1970s, when the conventional wisdom said it was impossible.

Don was also a powerful advocate for the Pennsylvania Federation of Sportsman’s Clubs, the National Rifle Association, and many other similar groups to which he was a devoted life member.

He was a persuasive advocate for the continued success of the Pennsylvania Game Commission on the whole, and its land acquisition and science-based habitat management programs in particular.

Don was both an incredibly good hunter, and at times also exasperating to hunt with. This is because of his own unique standards: He refused to shoot a gobbler (male turkey), unless it was both strutting and gobbling at the same time. Sneaking toms, peeping toms, cautious toms, running or flying toms he would not shoot, no matter how close or in range of his gun. None of those were sporting birds, in his estimation. Only a completely unaware longbeard was worthy.

Don and I turkey hunted together a number of times over the years, mostly in the central Pennsylvania farmland we both love. While it would be easy to regale Don’s skill as a caller and hunter, two instances come to mind that sum up the attraction of having Don as your hunting partner.

First was his wry humor. He meant it with love, of course.

“Mmmmmm, uh huh. That sounds like a turkey,” was a frequent back handed compliment from Don as I was scratching away on a friction call, mostly slates.

He wouldn’t care that my calling had actually lured in a nice longbeard to within range. That was no inoculation against the compliment. For Don, it was important to remind me that my calling could always improve, whenever he had the chance. And he was right, of course, as much as I do not like to admit it. That’s what good teachers are about. He was, after all, a many time champion caller whose skill I could only marvel at and never hope to replicate.

And just to prove his point by spiking the ball, Don might decide to stand up and switch locations even as the gobbler was determinedly marching across a cut corn field directly to us.

Watching the alarmed bird take wing and sail to the other side of the valley, the now standing Don said to my sitting figure, “Yeah, he must’ve seen you move.”

Movement is the biggest no-no of all in turkey hunting, and rookies move a lot. Even veterans get caught moving their eyeballs by wary gobblers fifty yards out. To attribute the alarmed and rushed exit of a wild turkey to a hunter’s movement is a gentle way of saying “Your hunting skill needs some work.” Even if it didn’t at that very moment.

And then there was that truly exasperating standard of his, the one where he would only shoot a gobbler in full strut AND gobbling. That performance is like looking up in the sky and seeing the sun and moon align, because a longbeard gobbler that is both strutting and gobbling is completely in the moment. He feels no fear or wariness that usually accompanies most alluring hen calls by hunters.

As I am not ever going to approach Don’s skill as a turkey hunter (he has racked up more annual grand slam turkey hunts species-wise and across multiple states than anyone else I know), I feel fortunate to shoot any gobbler, strutting or not.

And it is a fact that my poor skill as a turkey caller usually results in birds sneaking in, peering in, or darting in for a quick look before running like hell to get out of Dodge, or “putting” (turkeys make a putt-putt alarm call when they are suspicious enough to flee) from 40 yards out, so that most of the gobblers I have killed were shot mid-stride to the next county.

Not in full strut AND gobbling, like Don would have.

One morning in Dauphin County about four or five years ago, Don and I were lying in a field while I called to turkeys below us. They came well within range, but the lead gobbler, a huge bruiser boss bird, stopped gobbling and was “only” fanned out and puffed up, strutting. Such an impressive performance was insufficient to move Don’s trigger finger backwards, despite my harsh whispers of expletive-laced encouragement.

Nope. Instead, Don stood up in plain view of the flock, maybe thirty yards away, with his shotgun trained on the head of the strutting gobbler, and he began simultaneously calling with his mouth diaphragm call.

Wild turkey hunters know that at the sight of a man standing up within two hundred yards, let alone thirty, wild turkeys scatter like dust in a hurricane. They are gone in the blink of an eye.

Not these birds. Don’s calling was so good, so realistic, so enticing that the entire flock turned to look at us with concern for the grossly misshapen hen addressing them, and then they calmly walked away.

Don never shot, though he would have easily bagged any of the gobblers there. He just said “Oh, well, let’s go try another spot.”

Don is now in another spot, a turkey chaser’s dream spot, I am sure. He was diagnosed with an incurable brain tumor in late January this year, and he rode it out with the help of his devoted wife, Sandy, for the next few months, until he died on the night of May 17th, in the central Pennsylvania region he loved so much.

Like all of his friends and acquaintances, I will miss Don Heckman enormously. Sitting in a turkey blind I cried yesterday, thinking about his loss. Don died way too young, barely into his retirement, and not in time for me to prove to him that really, I can get a gobbler to strut AND gobble in range. But that is what I will continue to do, to aspire to, in Don’s memory, as representative as it was of one of the last great generational wildlife conservation leaders in Pennsylvania and in America.

Bye, old friend, boy do I miss you.

I am a happy PA Game Commission partner

For the past ten years, we have enrolled 350 acres in Centre County with the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s public access program.

We pay the taxes on the land, the PGC patrols the land, and the public hunts and traps on the land. From personal items left lying on the ground, like underpants and beer cans, it is clear that some members of the public are using it in more creative recreational ways.

Cleaning up these things is part of the burden we bear to provide the public with nice places to hunt and…”picnic.”

Because our land is surrounded by State Game Lands, it made sense to open it to the public. We were approached to lease it as a private hunting club, and we have resisted that for all these years. We recently sold 100 acres to PGC, and we wanted it to be a seamless experience for the public, used to walking in on a gated road and immediately hunting.

Overall our experience has been positive. Yes, we get frustrated by people leaving trash behind, when they could easily put it in the vehicle they brought it in with. But we take great satisfaction knowing that the majority of visitors are exhilarated to be there, and they use the land respectfully.

Our family is proud to help other Pennsylvanians have a beautiful place to hunt and trap, so that these ancient skills can be passed on to younger generations. We are proud and pleased to partner with the Pennsylvania Game Commission.

Tom Wolf & Republican legislature should agree on this, if nothing else

A version of the following essay was published by the Patriot News at the following URL: http://www.pennlive.com/opinion/2014/12/if_they_can_agree_on_nothing_e.html#incart_river

Conservation: An Area Where Democrat Tom Wolf and the Republican Legislature Should Agree

By Josh First

Land and water conservation are not luxuries, they are necessities in a world of growing demand for natural resources. As America’s population grows, the natural resources that sustain us, feed, us, cloth us, nurture us, warm us, and yes, even make toilet paper (and who can do without that), must be produced in ever greater supply.

Some of these resources are at static levels, like clean water, while others, like trees, are renewable. All are gifts that God commands us to manage wisely in Genesis.

Pennsylvania is facing some challenges in this regard, however, as the Susquehanna River shows serious signs of strain, and our world-famous forests face a devastating onslaught of invasive pests and diseases.

John Arway, executive director of the Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission, has been advocating for officially declaring the Susquehanna River an “impaired waterway” for years. The data Arway draws upon support his concerns: Dissolved oxygen so low that few animals can live in the water, one of three inter-sex (hermaphroditic) smallmouth bass populations in the country, a bass population with insufficient young to keep the species alive, the remaining bass covered in tumors and pfiesteria lesions, invasive rusty crayfish pushing out the tastier native crayfish, among many other factors. Once-abundant mayfly hatches are now non-existent.

Fishermen used to travel to Harrisburg from around the country to fish for smallmouth bass; not any more.

This past September a friend and I hunted geese out in the river, wading in our shorts. We saw none of the usual turtles, water snakes, birds, or fish that once teemed there, and the water smelled…odd. One day later, a small scratch on my leg had became infected with MRSA, and I spent four days hooked up to increasingly stronger antibiotics at Osteopathic Hospital.

In November, we canoed out to islands and hunted ducks flying south. Except that over the past ten years there are fewer and fewer ducks now flying south along the Susquehanna River. We speculate that there is nothing in it for them to feed upon, and migrating ducks must have turned their attention to more sustaining routes.

The river almost seems….dead.

Feeding the waterways are Pennsylvania’s forests, the envy of forest products producers around the world. Our state’s award-winning public lands and their surrounding mature private forestlands sustainably and renewably produce a greater volume of the widest variety of valuable hardwoods than any other state in America.

Our forest economy isn’t just about timber production, however, as hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation themselves represent large economic sectors. Our robust black bear and wild turkey populations draw hunters from around the world, but these popular species depend almost entirely on acorns from oak trees; without acorns, they would hardly exist.

The oak forests at the core of our world-famous hunting and valuable timber were once considered under the gun from overabundant deer herds, but with that problem now resolved they face an adversary that could turn them into the 21st century version of the American chestnut – sudden oak death disease.

Recall that the American chestnut, like the now-extinct passenger pigeon, once carpeted the entire east coast with unimaginably abundant white flowers and nutritious nuts that fed wildlife and humans alike, and its wood was a more available version of cypress – strong, rot-resistant, straight grained, easy to work. And then, like the once unimaginably vast swarms of passenger pigeons that had blackened the day sky until they also suddenly disappeared, the mighty chestnut was wiped out in a few short years, 100 years ago, by an imported disease.

Our oaks, ash trees, and walnut trees seem to be facing a similar doomsday right now.

Thousand cankers, emerald ash borer, lanternfly, ailanthus, mile-a-minute weed, Japanese honeysuckle, Asian bittersweet vine, and many, many other non-native invasive plants, bugs, and diseases now threaten our valuable native forests on a scale unimagined just a few years ago.

Ironically, the edges of our state and federal highways appear to be the greatest means of spreading these pests.

Today, Pennsylvania has a true balance of power between Democrat governor-elect Tom Wolf, and an overwhelmingly Republican legislature. There isn’t much policy that these two equal forces are going to agree on. But if there is one area that they should easily find common ground, it is land and water conservation.

Something is seriously wrong with the Susquehanna River, and something is about to be seriously wrong with our forests.

Whether a crushing regulatory response is the appropriate way to address these issues, or not, let’s hope that Pennsylvania state government can help fix these problems before they become catastrophes future history books write about.

Josh First is a businessman in Harrisburg

Fifty years of designated wilderness

Two weeks ago marked the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Wilderness Act.

It applies to federal designation of remote areas, not to states. States can create their own wild areas, and some do. States closest to human populations and land development seem to also be most assertive about setting aside large areas for people and animals to enjoy.

I enjoy wilderness a lot. Hunting, camping, hiking, fishing, and exploring are all activities I do in designated wilderness.

Every year I hunt Upstate New York’s Adirondack Mountains, in a large designated wilderness area. Pitching a tent miles in from the trail head, the only person I see is a hunting partner. Serenity like that is tough to find unless you already live in northern Vermont, Maine, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming or Alaska. It’s a valuable thing, that tranquility.

This summer my young son sat in my lap late at night, watching shooting stars against an already unbelievably starry sky. Loons cried out all around us. A gentle breeze rustled the leaves on the birch trees above us and caused the lake to lap against our rocky shore.

Only by driving a long way north, and then canoeing on a designated wilderness lake, and camping on a designated wilderness island in that lake, were we able to find such peace and quiet. No one else was anywhere around us. We were totally alone, with our camp fires, firewood chores, fishing rods, and deep sleeps in the cold tent.

These are memories likely to make my son smile even as he ages and grapples with responsibilities and challenges of adulthood. We couldn’t do it without wilderness.

Wilderness is a touchstone for a frontier nation like America. Wilderness equals freedom of movement, freedom of action. The same sort of freedoms that instigated insurrection against the British monarchy. American frontiersmen became accustomed to individual liberty unlike anything seen in Western Civilization. They enshrined those liberties in our Constitution.

Sure, there are some frustrations associated with managing wilderness.

Out West, wilderness designation has become a politicized fight over access to valuable minerals under the ground. Access usually involves roads, and roads are the antithesis of a wild experience.

Given the large amount of publicly owned land in the West, I cannot help but wonder if there isn’t some bartering that could go on to resolve these fights. Take multiple use public land and designate it as wilderness, so other areas can responsibly yield their valuable minerals. Plenty of present day public land was once heavily logged, farmed, ranched, and mined, but those scars are long gone.

You can hike all day in a Gold Mine Creek basin and find one tiny miner’s shack from 1902. All other signs have washed away, been covered up by new layers of soil, etc. So there is precedent for taking once-used land and letting it heal to the point where we visitors would swear it is pristine.

Out East, where we have large hardwood forests, occasionally, huge valuable timber falls over in wilderness areas, and the financially hard-pressed locals could surely use the income from retrieving, milling, and selling lumber from those trees. But wilderness rules usually require such behemoths to stay where they lay, symbols of an old forest rarely seen anywhere today. They can be seen as profligate waste, I understand that. I also understand that some now-rare salamanders might only make their homes under these rotting giant logs, and nowhere else.

Seeing the yellow-on-black body of the salamander makes me think of the starry night sky filled with shooting stars. A rare thing of beauty in a world full of bustle, noise, voices, and concrete. For me, I’ll take the salamander.

When the government just takes your land

About four years ago, Pennsylvania state government created a new regulation setting aside 150-foot buffers on waterways classified as High Quality and Exceptional Value.

This means that 150 feet from the edge of the waterway up into the private property, it’s designated as off-limits to most types of disturbances.

The purpose was to protect these waterways from the effects of development.

The end result is an obviously uncompensated taking of private property by the government. When the government takes a tape measure and marks off your own private land and says you can’t do anything with this huge area, or a road is going through, you’re simply taken advantage of. You’re robbed. It’s Un-American. It’s unconstitutional.

Pennsylvania is a great state. I love living here. It’s saddening to see such top-down, command and control, clunky, one-size-fits-all regulations in this day and age. We can do so much better than this approach.

To start, create incentives for landowners to go along. Give tax credits and write-offs for land taken by government.

Do we all want clean air, soil, and water? Sure. Breathing, eating, and drinking clean air, food, and water are necessary to surviving. But that’s not the question.

The question is HOW we pursue those goals.

Requiring American citizens to simply give up their investments, with no compensation, creates losers in a system that was originally designed to make everyone a winner.

Instead of pitting government against the citizens, we need policies and laws that help and serve citizens, that are fair to citizens. That is by definition good government.

This current 150-foot buffer regulation is by definition bad government.