Posts Tagged → fish

A thousand overnight tragedies

Normally, the smell of rotting fish is a signal to clean out the fridge or to leave the area you are in. It’s a universally bad smell, and no one normal wants to be around it. But it was a pervasive good sign where I happened to be standing, because it was associated with the freshly dead salmon heads and remains at my feet that had not been here the previous afternoon. A thousand individual tragedies had occurred along this stream bank overnight, as bears had picked muddy bank spots to grab spawning salmon and take them uphill where they could eat them without the fear of being ambushed by humans, or bigger bears.

We had hunted and fished along a roughly seventy mile vertical stretch of southeastern Alaska for over a week, and in addition to beginning to smell a little fishy myself, I had also saturated and possibly satiated a cavernous need inside me. It is an ever-present deep, clawing need that most wilderness seekers share, be they bikers, hikers, canoers, campers, photographers, fishers or hunters. Sorry, I am not going to quote Thoreau or Muir or Roosevelt on the tonics, joys, highs, or benefits of directly experiencing wilderness. My own wilderness pleasure is gained from simply not seeing a single other human being (except my hunting/fishing partner, when I have one) anywhere near where I am hunting or fishing. That unusual moment results in me feeling like I have better than average odds of achieving my goal, because I have the whole landscape to play without intervention.

On this trip, my “public” goal was a wolf, a blacktail deer, and/or a big black bear better than 300 pounds. Hides and skulls alone were going to come home with me. Edible meat was going directly into my buddy’s freezer. All of the many salmon I caught on the trip went into either my buddy’s smoke house, into his freezer, or into my stomach. It pleases me to report back that chum (dog) salmon directly out of the ocean taste damned good. It is also a fact that chum salmon do not keep well overnight, and that even halibut turn up their noses at it. I suppose freshly caught chum can be immediately canned, but given that there are usually better alternative salmon species to eat and can, I don’t see why a person would make this choice.

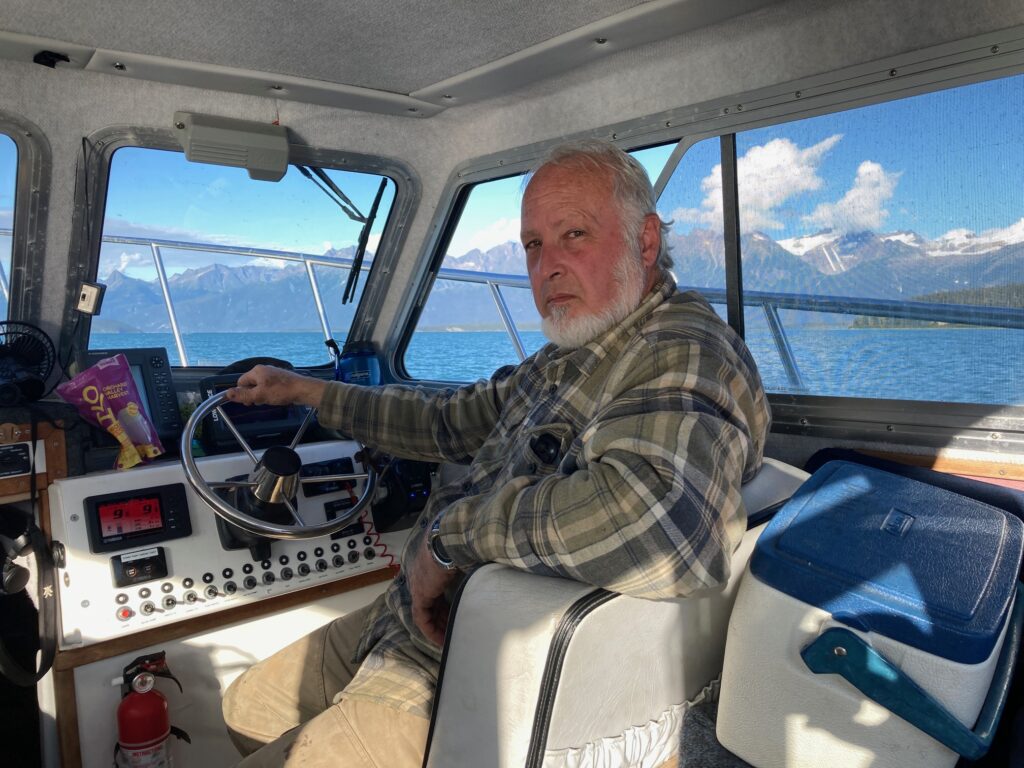

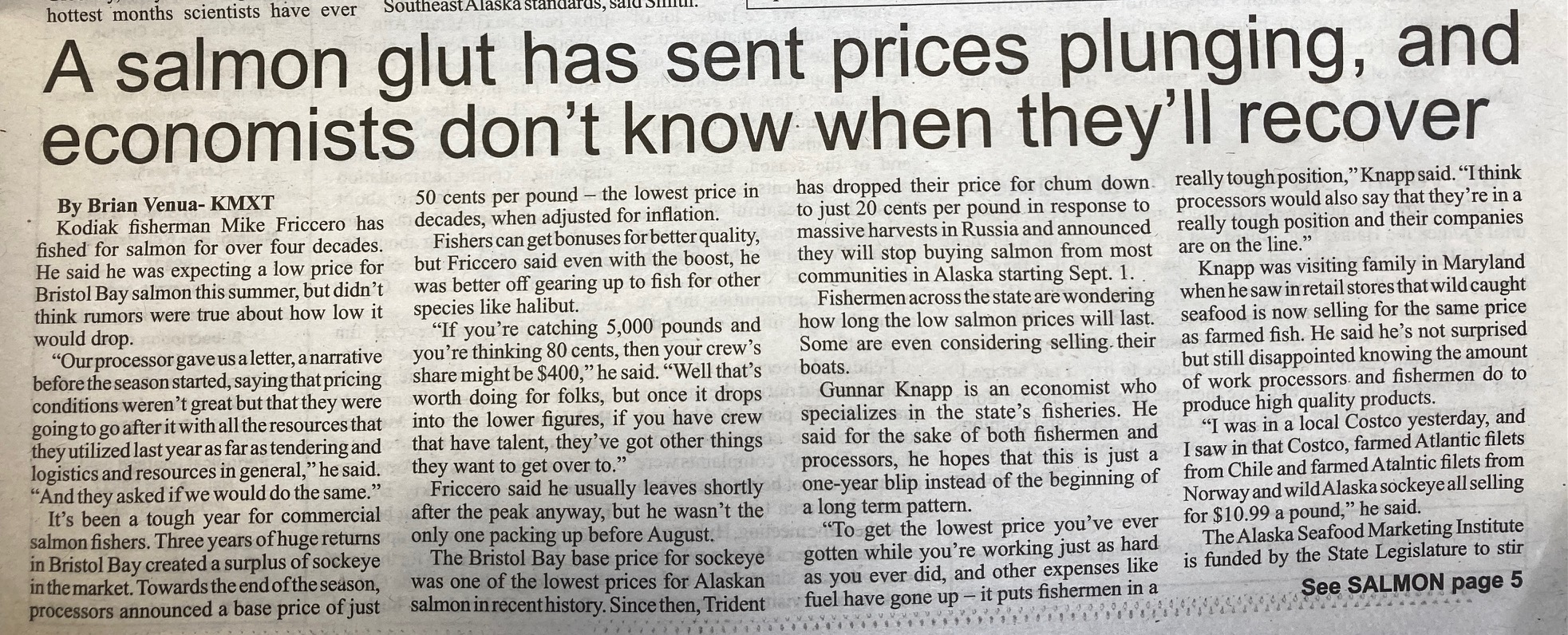

Incidentally, about those salmon: Alaska’s management of its salmon runs has been so good, so professional, so scientific, and so successful, that there is actually a glut of salmon in the streams and on the American market. Therefore, wild caught salmon prices are way down. A lot of commercial salmon boats were out netting, and the cannery we visited was in business, but with diesel fuel at about eight bucks a gallon there and salmon at eighty cents a pound, it’s hard to see how the netters will survive. But thanks to the Alaska Department of Fish & Game, the bears have plenty to eat before denning and hibernating for the long, cold Alaskan winter.

Goals are critical on a wilderness trip. Even stupidly simple ones. You have to have goals before you set out on a trip like this, or else you will wonder what the heck you were doing out there when you get back to civilization. My actual personal goal was simple: To fish and to hunt as much as I could, and this goal was easily met. On this trip, I was often able to do both hunting and fishing simultaneously: We slowly trolled salmon spoons behind the boat while glassing the shorelines for critters. A rubber dinghy towed in the backwash provided us the ship-to-shore transportation we needed. See a salmon stream that is calling your name? Go ashore and hunt it, and look for salmon-eating black bears to fill some tags; and look out for the griz. We saw a lot of griz.

Only saw wolf tracks in one very remote spot, and I passed up the one black bear I had a shot at. Only twenty feet across the salmon stream from me, he was either a genetic runt, an ancient-looking yearling, or maybe a female. Whatever kind of black bear he was, he was crabby enough to growl at me before shambling off to less crowded fishing spots. I wouldn’t shoot a bear that small in Pennsylvania, and I sure wasn’t going to fill my Alaska tag with it. Maybe I will go back for the spring bear hunt in 2024.

Despite fighting our way up into the interior of an island known to have blacktail deer, we saw none and feared the griz there more than we were willing to keep going after deer. Signs of griz were everywhere. I picked and popped high bush cranberry and high bush huckleberry while noting the increasing deer browse the farther in and higher I got. But it was a veritable jungle, and surprising a griz up here would mean my certain mauling, possibly my death, and so I decided to nicely frame my deer locking tag when I got home instead of risking life and limb to fill it. I headed back out and found Merlin asleep in the sunshine on the beach.

A loud thud on the bottom of the boat awakened me from my cramped sleeping position, and I rolled out of my sleeping bag onto the cabin floor, which was cluttered with gear and guns. Walking out onto the deck to look for the source of the thump, I saw a sea lion, a seal, and a pod of porpoises chasing salmon all around us in the early morning dimness. Mist rose from the water, and then the rosy tint of dawn’s first sunbeams lit up a nameless glacier high up in the crags across the water. I felt stoned on all this Mother Nature. Like I said, I was there just to hunt and fish, and whether or not I went home with the physically tangible results was not nearly as important as absorbing and sucking up the magic around me and filling that big, hungry, empty cavern in my soul. You just can’t have this magical experience without public lands, and some of that designated as wilderness. This, these, we had.

Alaskan salmon management has been so good that there are actually “too many” salmon, if there is such a thing

Reflected is the Chilkoot River, where we fished with the bears and a gaggle of international tourists following them up and down the river

Trolling spoons for salmon, towing our dinghy, and glassing the shoreline for critters. This is hunting and fishing at the same time

My hunting kit. A Henry 45-70 lever rifle (not crazy about the cheesy rear sight), a JRJ knife, rugged Leupold binoculars, home made dried fruit and jerky

Grizzly sow and cub eating salmon as they spawn upstream from the Chilkat River. I saw a lifetime supply of griz on this trip.

There is hope: Dinosaurs on the river

One of the reasons I object so strenuously to the fake climate alarmism nonsense is that it not only takes away attention and energy from real, measurable environmental problems, it also is so transparently fake and ridiculous that more and more Americans are beginning to doubt the entire environmental quality cause with which “climate change” is unjustifiably included.

When the public is lied to for five decades, told that the climate sky is falling, and that we have only five more years until… pick your fake end-of-times flooding, crop failure, too hot, too cold, end of oil, end of natural gas etc… and those predictions do not play out, then that public becomes weary and suspicious about everything the climate alarmists say, including the very real problems like loss of farmland, forest fragmentation, invasive bugs and plants, loss of wildlife habitat, loss of wild places. And that is bad, because Americans do need to maintain environmental quality, and improve it where needed. If we lose public support for true environmental problems that have real world solutions, then we will truly and needlessly suffer in the end.

Aside from being wrong about literally everything they claim and then demand, one of the other problems with climate alarmists is that they assume and promote a view of nature as steady state. That is, Nature never changes, it is always a Garden of Eden, except for human intervention. And when humans make mistakes or act greedily, climate alarmists say massive government intervention is needed, to the point where Western Civilization must be turned on its head, democracy must be canceled (for our own good, of course), and government bureaucrats must be in charge of every choice and decision we now make (we can’t be trusted to make “the right” choice). This is yet more nonsense, for the simple reason that Nature heals itself naturally.

How else does Nature recover from natural catastrophes like explosive and polluting volcanoes, floods, huge fires, meteor strikes, tornados etc? Well, Nature abhors a vacuum, and where a gap exists in Nature, some animal and some plant will adapt to exploit it and make room to live and grow in it. Even if the prior plant or animal can no longer live there.

In 2006 something very bad and mysterious was suddenly happening to the Susquehanna River. A hard-fighting smallmouth bass fishery so good (100-200 fish per day per fisherman) that fishermen came from all around the world to fish (and spend the night and spend their money locally) from Sunbury down to the Conowingo Dam in Maryland, was suddenly gone. Vanished. And gone along with the vanished smallmouth bass were the big predacious muskellunge, brown trout from the feeder stream mouths, largemouth bass, fallfish, sunfish, redeye, and shad.

Within just a few years a highly tangible and visible environmental catastrophe had revealed itself as a long stretch of the Susquehanna River literally went belly up and died. Native aquatic insects, the backbone of all life in the water there, disappeared. Up until 2005, you could stand on a late summer afternoon in Harrisburg along the Front Street Greenbelt walk and watch as the entire river surface practically boiled with dimples from rising fish eating hatching mayflies, caddis flies, and stone flies. In 2006 that whole activity ceased. Literally everything in the river died, and it still has not come back.

Long story short, what caused the demise of the Susquehanna River was a perfect storm of every bad thing that could happen to any waterway anywhere. If it could go wrong for the Susquehanna, it did go wrong in just a few short years, and the sum total was a total unmitigated shock and detonation of the waterway.

Several years of drought and unusually warm summers led to unusually low water flows, which left fish exposed and with no where to hide from predators. The over-heated water then developed algae blooms that robbed the water of its oxygen, suffocating fish and prey crustaceans like crayfish. When large summer thunderstorms happened, they overwhelmed and drowned the many community sewage treatment plants along the river, resulting in “Combined Sewage Overflows” up and down the river. These huge torrents of raw, untreated, undecomposed human filth blasted into the low, warm river water. There was no dilution of the mess, because the river was too low and too slow. One can only imagine that the conditions then were ripe for that human excrement to sit in still waters and become a feast for bacteria, which attacked the few surviving fish and left them with open wound lesions. Then viruses appeared, apparently rejoicing in the poor conditions, further attacking the remaining fish. Finally, when Pennsylvania’s shale gas boom started in 2006, there were some documented and suspected incidents of “midnight dumping”, where large tanker trucks filled with well brine or frack water were illegally unloaded into waterways that, of course, went into the Susquehanna River.

With the demise of the river’s fish, native grasses and watercress, the birds that migrated to, lived on, and migrated down the river, had nothing to eat. They also disappeared. Hundreds of egrets and herons, and huge rafts of ducks and geese used to grace the shores and skies above the river around Harrisburg on any given summer or Fall day. Not any more.

In 2005 one of America’s largest Great Egret rookeries flourished on the islands in the Harrisburg Archipelago across from Harrisburg City. My fishing buddy Ed Weintraub and I used to wade half a mile out to fish among the archipelago’s islands, and marvel at the hundreds of these gigantic pterodactyl-looking birds and their enormous nests. The place sounded like what a Jurassic jungle must have been like, with loud screams, cries, grunts, groans, and other weird sounds from the huge birds and their babies assembled in that relatively small place. All the boulders jutting out of the river were coated in bright white bird dookie, as were the trees. The entire place stank to high heaven of rotting fish. It was a natural marvel of human-Mother Nature coexistence that reflected the incredible environmental diversity and health of the waterway, despite it being surrounded by huge train yards and human communities. This all was also eventually lost to whatever was ailing the river.

In 2011, while kayaking and wading the unnaturally smelly river in Harrisburg, I contracted MRSA in a tiny scratch on my leg, and then spent four days on a drip IV in a hospital, successfully avoiding the loss of my leg. The river was deader than a doornail and I almost joined it.

Last week two of us took a nice long canoe trip down river, my first in years, to see how the river has changed. We see a few bass fishermen now, local catfish guides brag about sixty-pounders, and walleye boats are out every day. Something in the river must be improved. It seems to be healing, but it is nowhere near where it was twenty years ago. I know that the West Branch of the Susquehanna is greatly improved from twenty years ago, when acid mine drainage turned its waters an unnatural turquoise blue. Now those old mines are washed out by the subterranean springs that first unleashed the mines’ acid, and the cold water is now clean and actually improving the West Branch.

Large bass and catfish -a more rugged critter filling the void left by the formerly numerous smallmouth bass- scurried out of our shadow, and as we approached the Harrisburg Archipelago, we began to see Great Egrets wading around the upstream islands. Lots of them. A juvenile bald eagle patrolled above. We paddled around and through the Archipelago and were surrounded by cormorants (a federally protected pest), mallards, wood ducks, turtles, a snake, and lots of nesting Great Egrets.

The dinosaurs were back on the islands and so were my hopes for a comeback by the river. No metaphysical cataclysmic environmental or political catastrophes were required for Mother Nature to bounce back. She always does, and she always will, despite what the Al Gore type fakirs predict.

The Rockville Bridge is the longest stone arch bridge still in use in the world. I think it is longer than the Glenfinnan Viaduct in Fort William, Scotland, which I have ridden over in a train. The Susquehanna River is slowly recovering from the many things that ailed her, and is now a delight to experience.

Trump Great American Outdoors Act hits Conservation Home Run

Conservation is where I have spent my entire career, and it is where my heart resides day in and day out. So it is with great happiness that I see President Trump sign into law the Great American Outdoor Act, which will do the nuts and bolts environmental protection America needs, without the regulation that America does not need.

The fact that so many political appointees within the Trump Administration were cheerleaders for the GAOA says a lot about the political tenor there. So many people accuse the Trump Administration of being some kind of radical “right wing” blah blah, and the fact is that the entire administration is loaded with middle-of-the-road professionals, who hold a mix of political, philosophical, and ideological views. In past Republican administrations, there were plenty of appointees who would have blocked GAOA, or held it up. GAOA is a signature achievement for President Donald Trump, and it is a huge win for Americans.

GAOA fully funds the Land and Water Conservation Fund for the first time in a zillion years. It provides adequate funding for federal and state parks infrastructure updates, operations, and maintenance costs. These are the costs that are always deferred in every administration. It is a subject I wrote my master’s thesis on at Vanderbilt University, and it is a subject that has never gone away, until now: Federal recreational infrastructure has been woefully underfunded for decades. Many state parks across America are in even worse shape than that National Parks.

For example, in 2016 my teenage daughter and I hiked half of the Northville Placid Trail, which runs through the Adirondacks. At the end of our ninth day, as we waited out a looming thunderstorm in a rustic but comfortable lean-to deep inside designated wilderness, on a hike in which we had encountered only a few other people, my daughter sat looking at her dead iPhone. Like Gollum looking at The One Ring, only my daughter looked more disgusted and glum than happily mesmerized.

“I have to get out of here. I want to talk to my friends. I want to know what is happening in the world. We need to go,” she said, and picked up her backpack, jumped down onto the grass, then shouldered her backpack.

Oh, I tried to persuade her to spend the night and stay out of that coming downpour. But she would have nothing of it, and she set off by her own teenage self, going somewhere, maybe anywhere, and I was standing there watching her pick her way into the forest.

Hours later we emerged at Moose River Plains, what maps describe as a rustic New York State recreational area tucked away deep in the Adirondack wilderness. What we found was a boarded up main building, boarded up out buildings, no gate, and no official staff. Instead, a bunch of locals who regularly camp there had taken over the official duties of park rangers. Even the land line phone system was not working. It was a very kind local who drove us, each drenched to the bone and with sodden packs, to the closest village, where we could contact our driver and get back to our own vehicle parked at a Baptist church in Northville, so my daughter could get home and talk with a zillion friends simultaneously.

Turned out that Moose River Plains was victim to a New York State budget that prioritized funding illegal aliens, but not state parks.

The Moose River Plains experience was worse than our visit the year before to Saratoga National Battlefield, by far. But seeing Saratoga National Battlefield, where the brave fight for American freedom and independence was won, in such terrible disrepair and threadbare means, was frankly shocking. One expects the National Park Service to do so much better. And when we spoke with a park ranger there, she was clearly hurt, personally, as she explained the money constraints that park faced. NPS just could not get the job done.

All of this is to say that finally, money floweth in the right direction. The need out there for public infrastructure is almost beyond compute. It is about time that America invested in our national parks and forests, state parks and forests, local and county parks, and the myriad other adjunct little recreational areas, like Moose River Plains, so that Americans might enjoy our public outdoors.

And about that public outdoors thing: Public land is a public good. Public land is one of the very few things that government does pretty well. And even when government land managers fail, the outcome is almost always simple neglect; the land always remains, the wildlife habitat remains. Which means the opportunity for recreation, hunting, fishing, hiking, camping etc remains. It is not a real material loss when land managers screw up or there isn’t enough money to operate the park entrance gate house; just missed opportunities, and putting a frowny face on a public symbol.

Congratulations to President Trump for pushing hard for GAOA, for hiring the right kind of land management staff and public lands leaders, and for caring about our public lands at all levels – local, state, and federal. Trump understands Americans, and he knows how much we care about our public lands, our state parks. And he knows how important it is to constantly invest in those places, so that they don’t fall into disreputable disrepair, like Moose River Plains had fallen.

One of the parts of GAOA that is so very appealing to me is the public land acquisition funding. As development never sleeps, what were nice public spots to hunt or hike in suddenly find themselves cut off or surrounded or overrun by development. It is nice that states and local governments will finally be able to buy that ‘Mabel’s Farm’ the community always wanted, and could not afford.

There is going to be a lot of Mabel’s Farms bought with GAOA money in the next few years, a lot of Nature conserved, and a lot of communities and hunting places protected, as a result. Thank you, President Trump, conservationists everywhere appreciate your leadership on this important policy area.

With special people at Yosemite. Can we imagine America without Yosemite? It takes money to protect these special places.

My daughter at the unhappy lean-to. But still, it was a functional, dry lean-to next to clean water in the middle of ADKs wilderness

Our friends Mark and Amanda at Leonard Harrison State Park, overlooking the Pennsylvania Grand Canyon

My daughter at Cedar Lakes, a special moment that spurred her on to teach wilderness backpacking to kids. Now she can’t wait to reach the area of no cell reception

It’s that time of year again

Plenty of things have gone to hell in a hand basket over the course of the last four or five decades, and I would only be living up my highest and bestest reputation as a grouchy curmudgeon if I ticked them all off here as a laundry list of petty grievances. But other writers and commenters have already done all that, much better than I can, so I am going to mention just one frustration. And it must be credited to that mild mannered conservationist Aldo Leopold, who first put his finger on this, on the very beginning of what ails us Americans today.

If I read one more time the overused phrase “In a Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold writes…” I am going to scream. You are there and I am here on the other side of the screen, and we cannot actually hear one another, so it will sound like a silent scream, but rest assured, it drives me nuts and right now I am doing my best silent scream imitation about this. Sure, it is a testament to how inspiring Leopold was and still is that so (so) many people begin all kinds of talks and writings and poems with this opener, citing some comment or observation Leopold made back in the crusty 1940s Dark Ages that yet, surprisingly, has so much application and salience today, eighty years later. But it is so very much overused to the point where it is almost maudlin to hear it used yet one more time.

And then, when I think of those intervening eighty years, well, they have been both a blessing and a curse, haven’t they, and so I find myself in that recognizably similar frame of mind…

So what the hell.

In Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, he talks about cutting down a large oak tree with a crosscut saw, and how much history is gliding by as the saw blade traverses across the tree stem. For every few growth rings that are sawn, Leopold lists various wars and human milestones, scientific achievements as well as natural science moments, as the blade cuts deeper. Just that description alone is a pretty cool writing achievement by Leopold. It is a symbol and image that so many people have trouble forgetting.

But then at the end of the essay, just when the reader thinks “Yeah, I suppose cutting fire wood is more symbolic and meaningful than I thought it was, guess there’s a lotta history in those old oaks at Grandpa’s farm,” Leopold suddenly gets to the whole raison d’être of his history lesson (and I am closely paraphrasing here):

“I knew Americans were eventually doomed to cultural rot and failure when we discovered that heat came from a small switch on the wall, and not from cutting our own firewood every year.”

Here in the middle of his gentle outdoor lullaby, Leopold lamented the ease of life that had arrived with then-modern conveniences and services. He saw them as a two-edged sword, cutting both ways, for and against, because working hard for something, especially for your own ambient heat in the dead of winter, is an important lesson about how all humans are in truth part of the natural cycles around us all the time. Participating in these cycles humbles us, brings us into the actual healthy swing of things around us, helps integrate us with the earth’s natural vibe, tune, and wavelength, each of which we ride every moment of every day, even if we are unaware of it. And thus, it helps us thereby appreciate the natural world that sustains us every day. Even if we are unaware of it.

Leopold was advocating for Americans living newly cushy lives devoid of physical challenges to get the hell off their asses and live in the real world, to take responsibility for their own needs and not outsource everything (like the Romans did at their end). Cut their own firewood, grow a garden, shoot a grouse for dinner or a catch a fish for lunch. The ability to be self-reliant is not only an American trait from our frontier days, it is innately tied to all successful human cultures at all times.

Mind if we switch here to someone on the other side of the spectrum from our mild naturalist and wildlife biologist Aldo Leopold, who nonetheless expresses much the same sentiment?

“I hate luxury. I exercise moderation…it will be easy to forget your vision and purpose once you have fine clothes, fast horses, and beautiful women. [All of which will result in] you being no better than a slave, and you will surely lose everything.” — Genghis Khan (brutal conqueror of the entire known world in his time).

As that completely successful “mad butcher” said it, luxuries make humans soft and weak. Hard work makes us strong and successful. If there is a hallmark of modern America, it is that we are awash in luxuries and conveniences, to the point where the younger generations have no idea how we arrived here at this point, how much sacrifice was required to give them these fancy phones and coffees. Our younger people think that luxuries and easy comforts just fall like manna from Heaven.

So, to be the truest, best American you can be, why not cut some firewood?

Here in central Pennsylvania it is that time of year again, the time of year where if you have not yet stacked the last of your firewood in the woodshed, you damned well better get on with it. Ain’t no time to lose. Any week now Mother Nature can show up with a big old cold surprise, a major dose of early Winter, knock out the electricity to your town, and leave you at the mercy of serious cold temperatures. It’ll be nice if we have all of October to enjoy mild Fall weather, with no need to light the wood stove, but you never know what the future brings. Better to be prepared, right?

Funny how something so insignificant as cutting one’s own firewood can be synonymous with an entire culture’s success or failure.

Wildlife biologist Aldo Leopold smoked tobacco, owned guns, ate what he hunted, planted a garden every year, and cut his own firewood. If you have not read A Sand County Almanac, then get it, because a world of special delight awaits you there, and it will change your life.

This season’s supply of split firewood stashed in the old woodshed, which is due to be replaced in 2020

Public Lands: Public good, public love

Someone named this September “Public Lands Month,” and while I have no idea who did this, or why they did it, I’ll take it nonetheless. Because like the vast majority of Americans, I totally, completely, absolutely love public land. Our public parks, forests, monuments, recreation areas, and wildlife management areas are one of the greatest acts of government in the history of human governments.

As a wilderness hunter, trapper, and fisherman, I truly love the idea of public land, and I love the land itself. No other place provides the lonesome opportunities to solo hunt for a huge bear or buck, either of which may have never seen a man before, or to take a fisher and a pine marten in a bodygripper or on a crossing log drowning rig, than public land.

If you want a representation of what is best and most symbolic of America, look to our public lands. They best capture the grandeur of America’s open frontier, the anvil upon which our tough national character was hammered and wrought. It was on the American frontier that Yankee ingenuity, self-reliance, and an indomitable hunger for individual freedom and liberty was born. And yes, while it was the Indian who reluctantly released his land to us, it was also the Indian who taught us the land’s value, so that we might not squander it, using it cheaply, profligately, and indiscriminately. Public lands are the antidote to our natural inclination to use land the same way we use everything else within our reach.

Some armchair conservatives argue that our public land is a waste of resources. That it is a bottled-up missed opportunity to make even more-more money, and if only we would just blow it all up, pave it all, dam it all, cut it all right now, etc, then someone somewhere would have even more millions of dollars in his pocket, and daggone it, he really wants those extra millions on top of the millions he already has in his pocket. When all our farmland is paved, that same armchair conservative will have nowhere to grow food to feed us, and apparently he will learn to eat dollar bills (he already thinks Dollars are what we survive on, anyhow, so it’ll be an interesting test of reality meeting theory).

But the truth is it’s mentally sick to talk about how much money you can get for selling your mother, or for selling your soul, which is what our land is, take your pick. Hunger for more money than a man knows what to do with, notwithstanding. But some things are just not worth valuing with money, and no number of payments of thirty pieces of silver will ever, ever amount to anything in comparison to what is actually in hand, our public land.

Others complain that public land is communism, but what do they say about the old English and New England commons, where villagers pastured their collected cows? Were our forebears who fought at Bunker Hill fighting for communism? You know they weren’t. Sometimes sharing isn’t a bad thing, and sharing some land is probably one of the best things. If Yosemite or Sequoia National Parks were privately owned, no one from the public would be there, right?

Americans are fortunate to have in their hand millions of acres of public land that they can access, from Maine to Alaska to Hawaii and everywhere in between. Little township and county squirrel parks, big state forests and parks, and vast national parks like the Appalachian Trail and Acadia are all magical experiences available only because they are public.

It is true that LaVoy Finicum was murdered in cold blood by out of control public employees over a legitimate debate with tyrannical, unaccountable public land managers in Oregon. But that is not the fault of the public grazing land there, any more than a murder can be blamed on the gun and not the man who pulled its trigger. We need to hold accountable those who screwed over Finicum and those who murdered him, not blame the land on which it all happened. Despite some failings by public land managers, of which Finicum’s murder is a great and sad example, public land remains one of the very few things that government actually does well and right almost all of the time. Corrective action is just one new administration away, as selected by the voters.

If you want to see untrammeled natural beauty for campers and hikers, or if you want to experience bountiful hunting lands for an afternoon or a week, then look to the public lands near you or far away from you. Everything else – nearly 100% of private lands – is either dead, dying, or slated for eventual execution at the hands of development.

We need a lot more public land in America. We need more to love in life, and nothing compares to loving a whole mountain range, a river, a field or a forest. It will love you back with nurture and sustenance, too.

Hang glider leaps off of Hyner View State Park, surrounded by a couple million acres of Pennsylvania state forest and state parks

Down below Hyner View State Park is the Renova (Renovo) municipal park, with some historical artifacts from past freedom-ensuring conflicts, reminding the next generations of the sacrifices made so they can enjoy iPhones and Starbucks

Yours truly standing high up in the Flatirons above super-liberal Boulder, Colorado, in the background, demonstrating “Trump Over Boulder” in case any hikers had missed the shirt. None had missed its presence there, by the way. Lots of public land here, enough for everyone to share, even Donald Trump! (and yes, there are a lot of boulders here in the photo).

The author malingering around the Boulder, Colorado Chautauqua kiosk, silently taunting the invasive liberals gathered and passing through there. And in fact, the Trump shirt earned many double and triple-takes from fellow hikers, unused to experiencing diversity of thought. I did not bite those people, though I was tempted. Great public lands experience!

PA wildlife: damned if we do, damned if we don’t

Like every other state in the Union, Pennsylvania protects, conserves, and manages its wildlife through a combination of user-pays fees like hunting and fishing licenses on the one hand, and a helping of federal funding collected from user-self-imposed federal taxes on hunting and fishing equipment like boats, guns, ammunition, fishing rods etc on the other hand (the same people who buy the hunting and fishing licenses).

Yes, 100% of the nation’s citizenry benefits from the self-imposed taxes and fees paid by just 1% of the population: the hunters, trappers, and fishermen. Yes, you read that right: just 1% of the population is carrying 100% of the public burden.

And yes, as you are correctly about to say out loud, you and I will not see this bizarre and totally unsustainable arrangement in any other area of public policy. Not in roads, not in schools, not in airports, not in museums, not in anything else official and run for public benefit. And so, yes, it is a fact that wildlife agencies across America are perennially underfunded, and have been for so long that it’s now accepted as the way America does its wildlife business. Here in Pennsylvania, despite endless rising costs and endlessly more expensive public pensions, both houses of the PA legislature have long blocked the PA Game Commission from getting a hunting license increase in decades. So the PGC is even more behind the financial Eight Ball than most other state wildlife agencies. Hunters and wildlife managers in other states look at Pennsylvania and shake their heads. It doesn’t have to be this way, but it is.

Despite the obvious imbalance and weakness inherent in such a unique and faulty funding arrangement, for fifty years this approach worked pretty well, nationally and in Pennsylvania, with some states occasionally putting new money into holes that opened up in the regular wildlife funding support. Those states with significantly increasing human populations tend to be forced into dealing with inevitable wildlife-human conflicts more than other states, and when Mr. and Mrs. America are increasingly hitting deer with their cars, you can bet that they will demand their home state do something about it. So more money is found.

So along comes the Pennsylvania Auditor General, to investigate the management and expenditure of money at the PGC. And why not, right? The PGC is a public agency, and hunting license revenue is a public trust. So sure, go ahead, look into it, audit the agency. And so it was done, and some interesting things emerged just a bit over a week ago.

In the “Atta boy” column is the fact that there appears to be no corruption, graft, or misuse of scarce sportsmen’s dollars at the PGC. By all accounts, PGC is transparent and well run. Given how much the sportsmen are always scrutinizing the agency, we all figured as much. But it is nice to have our beliefs and trust confirmed like this. We love the PGC even more today than before the audit.

In the “Aww shucks” column is the revelation that PGC staff do not immediately deposit oil and gas royalty checks when they are received, nor does the PGC ascertain for itself if those royalty payments are accurate in the first place, instead trusting the oil and gas companies to do what is right on their own. Hmmmm….This is a potential problem area, and we are all glad the auditors found it. Anyone who knows the PGC can bet money on the fact that PGC staff are right now doing all of this payment followup with a vengeance. Look out, oil and gas companies!

But then there is the big weird issue, the biggest issue of all, where the auditors “discover” that the PGC is sitting on $72 million in the bank. And accordingly, the auditors immediately and erroneously ascribe this to bad money management. After all, they say, public money is meant to be spent. “If you got ’em, smoke ’em,” goes the ancient and totally irresponsible government approach to managing public dollars. After all, under normal budgeting culture, agencies that do not spend the money budgeted to them risk losing those dollars in the next budget cycle. Failure to spend money is correlated with a failure to implement an agency’s mission, and for senior agency managers, there is the usual ego factor; the bigger the budget, the bigger the…you know. This is the old approach to managing government funds, and it is wrong, and it certainly does not fit the PGC’s reality or targeted way of doing business.

Let’s ask you a question: If you knew your family was going to be receiving less and less money going forward, and yet your family costs would be held steady, wouldn’t you begin to bank any extra money you had, in preparation for lean times ahead? If your family is responsible, then yes, this is what you do, it is what we all do. And it is what the PGC has done, thankfully.

But as a result of the audit, this single fact is being used to beat on the agency, to coerce the PGC to adopt unsustainable policies and irresponsible money management, despite the agency sailing through ever less sustainable funding waters every day. Seems like now every elected official and every Monday morning quarterback sportsman has some variation on the foolish theme that PGC has more money than it knows what to do with. Wrong!

So the real outcome of the audit is that Pennsylvania wildlife are damned either way, because the PGC is the useful straw man whipping boy for every aspiring demagogue in Pennsylvania politics. No matter what the PGC does, our wildlife resources are going to suffer. If PGC carefully, frugally husbands its limited resources, preparing for rainy days and needy wildlife, then the agency’s critics say the agency is miserly and hoarding, and they seek to punish the agency. And on the other hand, if the PGC immediately spends every dime it has, and has no money left over to deal with yet more unfunded mandates like Chronic Wasting Disease, then critics say the agency is wasteful and ineffective, and they seek to punish the agency.

And either way, the net result is the PGC’s critics damn and condemn our wildlife. Because that is the true result of all this second-guessing and monkeying about with the PGC budget and funding streams. Plenty of elected officials use their criticism of the PGC to artificially burnish their “good government” credentials, when in fact they are demanding the worst sort of government, and a total disservice to the sportsmen and wildlife everyone enjoys.

Many years ago, sportsmen were organized enough to react strongly to political demagogues who threatened our wildlife resource (and PA’s $1.6 billion annual hunting economy) with their petty politics. This latest iteration of the politics of wildlife management indicates that we need to get back to the old days, where sportsmen were unified and forceful, even vengeful, in their expectation that their elected officials would not politicize or hurt our commonly held wildlife resource.

A rock from the basement of time

Norman McClean wrote his book “A River Runs Through It,” about his childhood in southwest Montana. Growing up hunting and fishing brought him into close contact with unusual examples of natural history in the field, including really neat geological samples.

Those rocks that he found were what his Presbyterian minister father called “rocks from the basement of time.” Meaning that they were very old, from the beginning of the world. McClean effectively connects his reader with the sense that while standing in a trout river in Montana, holding one of these ancient rocks, he was transported, and the reader along with him, into a kind of time machine and also a giant web of life and history.

This phrase “rocks from the basement of time” always stuck with me, as it is so illustrative of how such basic, simple, everyday things in our lives can yet be so important or significant. And inspiring.

Here below is one such rock from the basement of time, but from this northcentral Pennsylvania corner of the world’s basement.

This large, rounded river cobble was unearthed today in the dirt bank behind the cabin in Pine Creek Valley, about four hundred feet above the Pine Creek riverbed. This rounded river stone started out as a squared chunk of slate hundreds of millions of years ago, and was then gently rounded and sculpted by flowing water, and sediment and rocks being pushed downstream over who knows how long. Its most recent path in its long life had it deposited in the great flood that created Pine Creek as we know it today, 10,000 years ago, after the most recent ice age.

At the end of that last ice age, a huge ice dam in the Finger Lakes region melted and burst, pouring an entire inland sea down through the little creek bed that was then north-flowing Pine Creek. All that water flooding the river channel caused Pine Creek to reverse its flow, and in that process enormous amounts of both shattered rock and rounded riverbottom cobble churned its way south, settling out along the walls of the canyon, eventually far far above, almost impossibly above, the new river channel and bed.

When I think about that raging torrent of mud and rock from a hundred miles upstream, filling up the valley’s river hundreds of feet higher than its usual height, and depositing ancient large river stones far above their natural resting place, I think “Wow.”

And here at my feet is all of that incredible story, told in one pretty much otherwise unremarkable rock from the dirt bank behind the cabin. Which I now look at and think of as being part of the basement of time. And suddenly I feel totally differently about my life and everything in it.

First Super Bowl I’ve Ever Missed

This will be the first Super Bowl I have not watched or participated in some way.

Every year we have a nice party at our home. Lots of food, friends, good cheer and great company. People come, they go, they return, the kids play downstairs where they have their own TV. It has always been a fun time.

However, because the NFL has decided to become involved in anti-America politics, I am giving the NFL a wide berth this year. I have not watched even one second of one game this season, and I will not be watching the Super Bowl, either.

Instead, this Sunday I will be at the PA Farm Show Building, volunteering to cover the PA Federation of Sportsman’s Clubs booth at the Great American Outdoor Show. At the GAOS, I will be greeting fellow outdoors folk, talking up hunting, trapping, and fishing, and reminding visitors of the need for solidarity among sportsmen.

Reminder: The PFSC started the outdoor show that is now the GAOS, back in 1954. And it was I who wrote the call to boycott former show promoter Reid Exhibitions, after they refused to allow modern sporting rifles in the show, and it was PFSC leaders who spread the boycott call far and wide and started it going and which drove off the British-owned Reid Exhibitions and paved the way for the NRA to take over the show. So the PFSC has been central to the GAOS and all the good stuff that goes with it for a very long time.

Here in Pennsylvania we have an unusual arrangement that no other state has. We have a league of exceptional people, dedicated to wildlife and habitat conservation, sound policy, and full-throated Second Amendment freedom. No other group in America, much less Pennsylvania, does what the PA Federation of Sportsmen’s Clubs does at the state level. Everyone benefits from PFSC’s daily work at the Capitol: Birders, wildflower enthusiasts, hikers, and yes, hunters, trappers, and fishermen, too.

One way GAOS visitors can support the outdoor sports is by purchasing a PFSC $5 raffle ticket. Every year people win nice guns and lots of money. It is a good investment, because even if you don’t win (and I never win), you are supporting PFSC’s full-time lobbyist and part-time support staff, so that all outdoorsmen have a constant voice in politics. PFSC is the main reason Pennsylvania bears no resemblance to our surrounding states, with their crazy anti gun laws and emphasis on animal “rights.”

Sorry, NFL, aka Kaepernick and Roger Goodell, you have made yourself irrelevant to me, and by acting so aggressively against America, you have reminded me and many other Americans of what is most important. It’s not entertainment, it’s not beer commercials (Budweiser has a pro-open borders ad, so kiss that beer goodbye from our future family purchases), it’s not hotdogs or even the company of friends. What matters most is bolstering the people and the values that have always made America great. And here in Central Pennsylvania, that means keeping company with fellow outdoorsmen.

See you at the GAOS! And God bless America.

The Bob Webber Trail takes on a whole new meaning

The Bob Webber Trail up between Cammal and Slate Run in the Pine Creek Valley is a well-known northcentral Pennsylvania destination. Along with the Golden Eagle Trail and other rugged, scenic hiking trails around there, you can see white and painted trilliums in the spring, waterfalls in June, and docile timber rattlers in July and August, as well as large brook trout stranded in ever-diminishing pools of crystal clear water as the summer moves along.

Bob Webber was a retired DCNR forester, who had spent the last 40 years or so of his life perched high above Slate Run in a rustic old CCC cabin. That is the life that many of the people around here aspire to, and which I, as a little kid, once stated matter of factly would be my own quiet existence when I reached the “big boy” age of 16. Except Bob had been married for almost all of his time there. He was no hermit, as he enjoyed people, especially people who wanted to explore nature off the beaten path.

That Bob had contributed so much to the conservation and intelligent development of Pine Creek’s recreational infrastructure is a well-earned understatement. He was a quiet leader on issues central to that remote yet popular tourist and hunting/fishing destination. The valley could easily have been dammed, like Kettle Creek was. Or it could easily have been over-developed to the point where the rustic charm that draws people there today would have been long gone. Bob was central to the valley’s successful model of both recreational destination and healthy ecosystem.

A year ago, while our clan was up at camp, Bob snowshoed down to Wolfe’s General Store, the source of just about everything in Slate Run, and I snapped a photo of my young son talking with both Bob and Tom Finkbiner, one of the other long-time stalwart conservationists in the valley. Whether my boy eventually understands or values this photo many years from now will depend upon his own interest in land and water conservation, nature, hunting, trapping, and fishing, and bringing urbanites into contact with these important pastimes so they better appreciate and value natural resources.

Bob, you will be missed. Right now you are walking the high mountains with your walking stick in your hand, enjoying God’s golden light and green fields on a good trail that never ends. God bless you.

Tom Wolf & Republican legislature should agree on this, if nothing else

A version of the following essay was published by the Patriot News at the following URL: http://www.pennlive.com/opinion/2014/12/if_they_can_agree_on_nothing_e.html#incart_river

Conservation: An Area Where Democrat Tom Wolf and the Republican Legislature Should Agree

By Josh First

Land and water conservation are not luxuries, they are necessities in a world of growing demand for natural resources. As America’s population grows, the natural resources that sustain us, feed, us, cloth us, nurture us, warm us, and yes, even make toilet paper (and who can do without that), must be produced in ever greater supply.

Some of these resources are at static levels, like clean water, while others, like trees, are renewable. All are gifts that God commands us to manage wisely in Genesis.

Pennsylvania is facing some challenges in this regard, however, as the Susquehanna River shows serious signs of strain, and our world-famous forests face a devastating onslaught of invasive pests and diseases.

John Arway, executive director of the Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission, has been advocating for officially declaring the Susquehanna River an “impaired waterway” for years. The data Arway draws upon support his concerns: Dissolved oxygen so low that few animals can live in the water, one of three inter-sex (hermaphroditic) smallmouth bass populations in the country, a bass population with insufficient young to keep the species alive, the remaining bass covered in tumors and pfiesteria lesions, invasive rusty crayfish pushing out the tastier native crayfish, among many other factors. Once-abundant mayfly hatches are now non-existent.

Fishermen used to travel to Harrisburg from around the country to fish for smallmouth bass; not any more.

This past September a friend and I hunted geese out in the river, wading in our shorts. We saw none of the usual turtles, water snakes, birds, or fish that once teemed there, and the water smelled…odd. One day later, a small scratch on my leg had became infected with MRSA, and I spent four days hooked up to increasingly stronger antibiotics at Osteopathic Hospital.

In November, we canoed out to islands and hunted ducks flying south. Except that over the past ten years there are fewer and fewer ducks now flying south along the Susquehanna River. We speculate that there is nothing in it for them to feed upon, and migrating ducks must have turned their attention to more sustaining routes.

The river almost seems….dead.

Feeding the waterways are Pennsylvania’s forests, the envy of forest products producers around the world. Our state’s award-winning public lands and their surrounding mature private forestlands sustainably and renewably produce a greater volume of the widest variety of valuable hardwoods than any other state in America.

Our forest economy isn’t just about timber production, however, as hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation themselves represent large economic sectors. Our robust black bear and wild turkey populations draw hunters from around the world, but these popular species depend almost entirely on acorns from oak trees; without acorns, they would hardly exist.

The oak forests at the core of our world-famous hunting and valuable timber were once considered under the gun from overabundant deer herds, but with that problem now resolved they face an adversary that could turn them into the 21st century version of the American chestnut – sudden oak death disease.

Recall that the American chestnut, like the now-extinct passenger pigeon, once carpeted the entire east coast with unimaginably abundant white flowers and nutritious nuts that fed wildlife and humans alike, and its wood was a more available version of cypress – strong, rot-resistant, straight grained, easy to work. And then, like the once unimaginably vast swarms of passenger pigeons that had blackened the day sky until they also suddenly disappeared, the mighty chestnut was wiped out in a few short years, 100 years ago, by an imported disease.

Our oaks, ash trees, and walnut trees seem to be facing a similar doomsday right now.

Thousand cankers, emerald ash borer, lanternfly, ailanthus, mile-a-minute weed, Japanese honeysuckle, Asian bittersweet vine, and many, many other non-native invasive plants, bugs, and diseases now threaten our valuable native forests on a scale unimagined just a few years ago.

Ironically, the edges of our state and federal highways appear to be the greatest means of spreading these pests.

Today, Pennsylvania has a true balance of power between Democrat governor-elect Tom Wolf, and an overwhelmingly Republican legislature. There isn’t much policy that these two equal forces are going to agree on. But if there is one area that they should easily find common ground, it is land and water conservation.

Something is seriously wrong with the Susquehanna River, and something is about to be seriously wrong with our forests.

Whether a crushing regulatory response is the appropriate way to address these issues, or not, let’s hope that Pennsylvania state government can help fix these problems before they become catastrophes future history books write about.

Josh First is a businessman in Harrisburg