Posts Tagged → bird

Some wonderful people gone

Jokes abound about aging, and quite a few are about those friends and family members who do not age with us, but who leave us all as we continue our own trajectory. Well, I am now definitely in the “aging” category and I am increasingly surrounded by people I enjoy and love who suddenly depart from this life. Recently two people here in Pennsylvania have left us all, and moved on to the spirit world, who I would like to mention. And it’s no joke, this dying thing. No matter what age a person is when they depart this life for the next, there is nothing funny about it.

Except maybe the last day on earth of European-Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, whose wild and often debauched Marxist Bohemian lifestyle made for intriguing movies and books. While some or maybe even a lot of the facts of Frida’s life may be funny depending upon the person considering them, her actual physical departure from this planet really is funny. I think.

After Frida died relatively young from cancer, or whatever it is that eventually afflicts the heavily debauched, her friends had her corpse dressed beautifully in her most customary colorful and flamboyant way, and prepared themselves all for a formal cremation send-off party in whatever crematory was present in Mexico City at the time. Her friends gathered in the crematory room while Frida’s corpse was ceremoniously loaded into the burn chamber, and as the roaring natural gas flames came to life, they all raised their glasses and toasted Frida.

And then the room erupted in gasps, cries, and people running for the exits, because suddenly Frida’s corpse stiffly bent at the waist, sat up, and made a wicked grin as her abundant hair caught on fire and created a demonic flaming halo around her yet untouched face. She wasn’t actually gone!

Yes, this was all her body’s muscular reaction to the sudden burst of 2,000-degree heat enveloping it, but apparently if you knew Frida, you kind of didn’t expect her to just die, you know, lie still and never move again. And indeed, she had lived up to all the hype about her, even while lying quite dead in the cremation chamber. I think this true story is funny, even though I did not know Frida and was not present at her cremation.

What is not funny and yet is not unexpected is the recent departure of Jim Brett, of Lenhartsville, PA, which for our geographically challenged readers is just north of I-78 and just south of Blue Mountain in Berks County, PA. Still confused where Lenhartsville, PA, is? OK, yes, it is the equivalent of East Succotash, PA, Nowheresville, PA, etc., and it is just about next to Hawk Mountain, the internationally famous sanctuary devoted to conserving birds of prey, especially on their annual migration south. There, solved this location question for you.

Hawk Mountain started as a simple land purchase to keep the shotgunners from standing on Blue Mountain’s highest Tuscarora sandstone boulder ridgetop and mindlessly swatting down out of the sky nearly every raptor that flew by on its way to South America. And in short order, more land purchases were added to what is now called the Kittatinny Ridge migration corridor. Hawk Mountain eventually became an educational organization and a destination for birders.

In the 1930s, birds of prey (hawks, owls, eagles, kites, vultures) were considered pestilential nuisances to farmers’ chickens and the rabbits and pheasants hunters enjoyed pursuing. In time, around the 1930s, raptors gradually became understood by some Americans as an important part of a healthy and properly functioning ecosystem, just as balanced populations of wolves, bears, mountain lions, bobcats and fishers have been subsequently understood today.

Hawk Mountain is now the world’s oldest continuously functioning conservation organization, but from 1934 to 1966 it was kind of a hidden gem, a hole in the wall of Blue Mountain that only certain initiates knew about or appreciated. It became much better known and more widely appreciated and much visited after Jim Brett became its second “curator,” as the chief executive position there is uniquely called.

As its leader, Jim Brett elevated Hawk Mountain to international status, built lots of buildings, hired lots of staff, attracted a lot of visitors, raised a lot of money, and he became a leading voice in bird conservation around our little blue and green planet.

On the outside, Jim Brett was a colorful Irishman, full of naughty jokes and a singular ability to imbibe liberally (often of his own make) and then hold forth to a captivated audience about biological and ecological science. But because Jim’s mother was Jewish, he had a separate interest in Israel, which, because it sits on a physical crossroads, is a lot like Blue Mountain. Israel is a birding Mecca.

A “sh*t ton” as Jim would say of raptors, storks, and other incredible and rare bird populations migrate through Israel, and Jim made their conservation from one end of their migration to the other one of his life’s missions. His Jewish half worked well with the Israelis, and his Irish half worked very well with the surrounding populations. One of his crowning achievements was working with Yossi Leshem to resolve bird strikes on Israeli fighter jets.

By finding ways to greatly reduce large rare birds being suddenly introduced to fighter jets at 1,000 mph, Yossi Leshem & Co. were able to save the lives of said rare birds, said giant titanium war eagles, and unsaid but implied young fighter pilots. It really was one of the great wild birds-living-with-modern-humans conservation success stories.

I met Jim Brett in 1998, when I had started working at PA DCNR in Harrisburg (having fled the corrupt and destructive US EPA in Washington DC). He was giving a presentation at an environmental and conservation education conference in Harrisburg, PA, and as the DCNR director of said polysyllabic educational field, it was my duty to both speak and to listen. Jim was standing up on the stage showing ancient stone tool artifacts and explaining the nexus between primitive hunter-gatherer lifestyles and the conservation or decimation of wildlife. I was hooked immediately.

Jim and I maintained a close personal and professional relationship until Fall, 2009, when I ran in a congressional primary (I was prompted to run by the devoutly corrupt and evil Manchurian Candidate Barack Hussein Obama, then president for nine months). My expressing my long quietly held political views educated not just Jim, but a sh*t ton of my “friends” and fellow conservationists alike about my true self. Gasp. Turned out that Jim did not know how conservative I was, and I did not know how liberal Jim was, and despite my desire to remain close, Jim had a hard time with it.

After 2009, our relationship involved less and less personal time, and fewer phone calls. I still have a generous gift that Jim gave me, which I occasionally take out and look at, admire, and then put it back in its safe place.

Jim and I stayed in touch through mutual friends for many years, including those who went on his African safaris he led. I can still recall Jim describing the funeral rite for a young son of a Maasai tribal leader, which he witnessed some time in the 1980s, I think: The boy’s body was ritually washed and then slathered in lamb fat, then put in the chieftain’s hut. The entire village was then evacuated and moved to an entirely new location, where a new settlement would be constructed. After the hyenas had entered the old village and consumed the boy’s body, the entire place was torched and left to become natural ecosystem thereafter.

Jim’s bright blue eyes flashed as he told this story, as indeed one would expect from someone so in tune with the endless hidden vibrations of our magical natural world. Though I know his spirit is now soaring with the majestic raptors, I doubt Jim’s liver will ever go the way of the hyena, Frida, or any mortal flesh for that matter. His official obituaries are here and here.

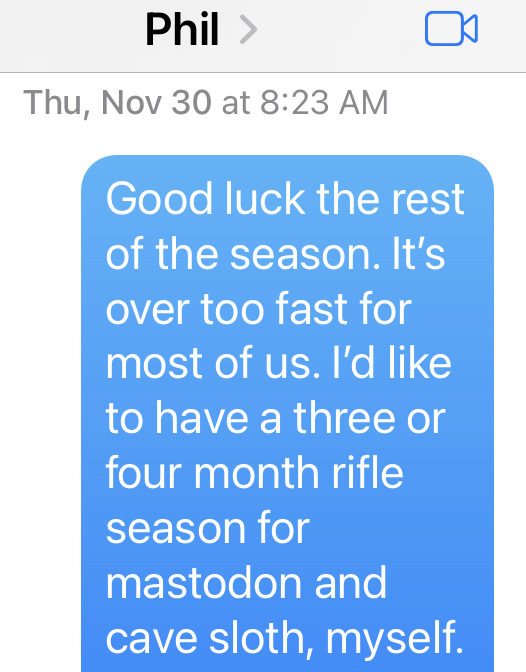

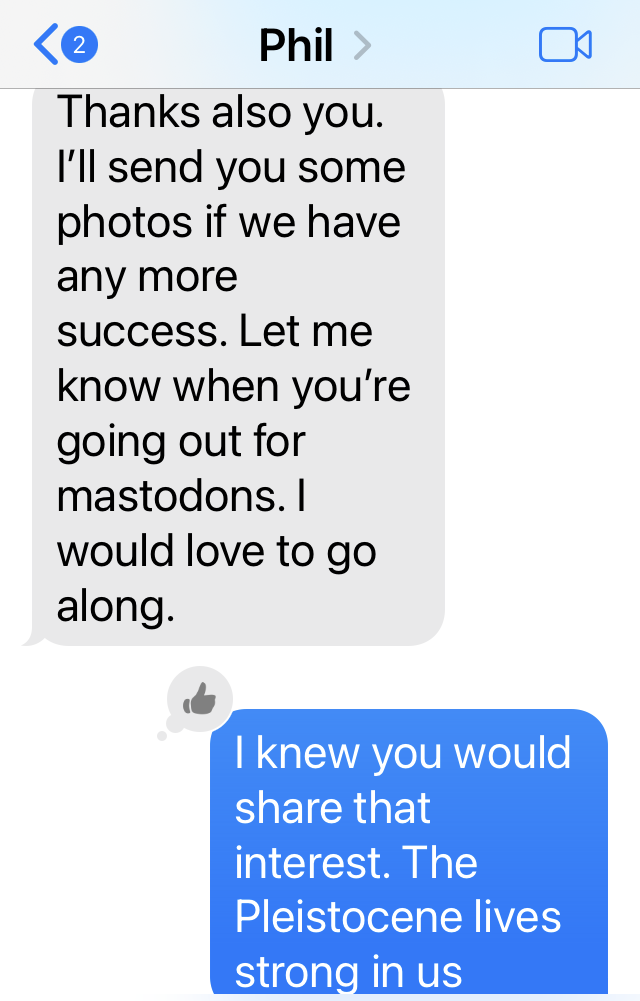

A second loss is someone I knew less closely, but with whom I shared a great deal in common and with whom I filled my buck tag this season: Phil Benner of Liberty, PA.

Until he unexpectedly died of Covid several days ago, the incredibly physically fit Phil Benner was a devoted father, a devoted husband, a devoted brother, a devoted uncle, a devoted son. He was a hard working small business owner, a risk-taking entrepreneur, and a pastor who saw God and felt Him deeply in the natural world around him, including the leaves rustling in the winter tree branches, and the quiet tinklebell sound of a small mountain stream’s clear waters falling over boulders. He appreciated everything and took nothing for granted.

Not only will I miss Phil Benner, the world will miss Phil Benner, because the world needs a billion more gentle, charitable, loving, devoted, kind, tolerant, peaceful Phil Benners. His loss is huge.

Phil Benner and his son Nate with a large bodied six point buck taken in Pine Creek Valley in late November, 2023

Midsummer report

My apologies for the long absence here. Summer is in full swing and our family has been operating at full tilt speed. Time only for doing things, and none for writing about it all, until now.

First off, our oldest kid was married on Independence Day. Held at a pretty and historic farm, it was a fantastic wedding, and we feel like we acquired a wonderful addition to our family. However, the preparation necessary for that event took up a lot of time and energy, for many months. And then there was the recovery week. And then there was the vacation week. Hence no blog posts. Full credit to my wife for all of the wedding planning.

At least I myself am back in the saddle, while other people around me are still recovering from their vacation. Not everyone does well with the surf fishing bum lifestyle, including sleeping on the beach, eating questionable food from a warm cooler that has been pawed over and drooled on by feral raccoons, and drinking fetid water. I myself thrive in this kind of environment, and so I am back to report back to our three readers.

What can I say about the wedding other than I fired our small black powder cannon seven times, for good luck. It was Independence Day, and while the venue does not allow fireworks, they did allow the cannon (it’s a cast iron, steel sleeved replica swivel gun with a 1.75″ bore). And in my speech as the bride’s father, how could I miss an opportunity to point out that Independence Day was brought to us by citizens with guns? That is a fact, is it not?

And (of course, I guess) I heard back afterwards that some of our wedding guests were offended by the cannon and also offended by my mention of the origins of American freedom – citizens with guns. You can’t make this stuff up if you tried, like it’s a Hollywood movie script caricature of spoiled rotten children who get everything that Planet Earth can provide and yet nonetheless complain about it. Something like “The food here is terrible and the portions are so small.”

Are Americans now really offended by Independence Day fireworks? Are they offended by displays of patriotism and mentioning of historical facts that unfortunately run contrary to some evil political narratives that privately owned guns are bad and our freedom was brought to Americans by a immaculately conceived federal government that descended from Heaven? Are some wedding guests now so crass that they actually complain about the bride’s father setting off his celebratory toy cannon for the enjoyment of all the normal fun-loving people in attendance?

I have a hard time believing these things, but I did get to witness this stuff. America is in big trouble when its own citizens, young and old, hate its founding and can’t give a proud father his one moment and some space to celebrate it. Jiminy crickets.

Just returned from a subsequent beach trip to a a long spit of federally managed property on the east coast. The National Park Service rangers were 99% normal, nice, intelligent Americans, thank you very much, Gage, Donald, and Stephen.

In this national park there is a problem with artificially high numbers of deer, foxes, and racoons. They have no natural predators and they are multiplying at breakneck rates and having huge negative impacts on the environment and local ecology. Vegetation shows a distinct deer browse line about four feet above the ground, and the racoons are everywhere, aggressive, and aiming to ruin your trip. I watched a red fox steal a camper’s breakfast sausage meal right off of his plate on the guy’s picnic table. We had raccoons patrolling our campsite and under our table as soon as we broke out our food. They will grab your food right out of your hand. It is a fact that raccoons are host to some nasty parasites they excrete in their poop, which was abundantly displayed all around the campsites. Raccoons are also the number one vector for rabies among wildlife.

Aside from posing health threats and incessantly badgering the humans who are trying to enjoy the park, the foxes and raccoons also eat the eggs of rare nesting shore birds. These rare birds enjoy huge swaths of cordoned off human-free dunes and beaches in the park (and also on federal and state lands out on Long Island, like Orient Point and Montauk). And yet the same exact NPS staff enforcing the human no-go dune zones policy are absolutely fine with the overabundant nest-raiding foxes and raccoons that render all the no-go zones meaningless. The staff do not support hunting or trapping these destructive pests, either to improve the park visitor experience or to protect the natural environment.

How can the rare birds successfully nest on the ground and hatch their chicks there when the artificially super overabundant egg-eating raccoons and foxes are allowed to roam at will?

Talking with various National Park Service staff about this problem resulted in exposure to various levels of education and serious/unserious mindset. Most of the NPS staff acknowledged there is a wildlife problem on site that must be addressed. Hunting the deer and trapping the foxes and raccoons is the normal and responsible way to deal with this artificial human-caused environmental problem. These are the responsible and serious ways of addressing a visitor problem on land that is owned by the US taxpayer and whose management is entrusted to taxpayer-paid bureaucrats.

However, when I mentioned the above normal solutions to a young, handsome, tall NPS Park Policeman patrolling our campground, he responded “The same can be said about humans — there are just too many humans. And your solution to the overabundant raccoon problem is not humane.” He would get rid of the humans and allow the artificially high numbers of nuisance wildlife to proliferate. With taxpayer-paid federal employees of this guy’s low caliber and high wokeness quotient, the park visitor experience is going to degrade. C’mon, NPS, you can screen your employee applicants better than this. This foolish people-hating young guy should never have a gun and a badge, much less wear an NPS uniform.

Overall the surf fishing was fun if mostly unproductive. Probably due to the high heat and ferocious sunshine. I can report that catching cownose/ bullnose rays on strong surf tackle is a hoot, but then safely decoupling that animal from the tackle is a whole other thing. They whip their barbed tails around trying to nail the fisherman, who is trying to release them back into the ocean (I learned to place something heavy on the tail while using heavy pliers to remove or break off the hook). We did witness a large shark violently feeding close to shore, and it would be a fair guess to say it was probably eating these rays, which we caught and saw in abundance on both the bay side and the ocean surf side.

So that is the mid-summer report. Fast action, lots of family, some big family celebration and lots of family movement across the beautiful American landscape for work and vacation. I hope that you the reader are also enjoying your summertime. Summer is such a glorious time to be with family and friends, to visit new places, to camp out under the stars and cook over an open fire, to think through life’s normal challenges and to spend time with people we love…and then it is over just when we are all starting to really get into it.

So make the most of your summer.

Campsite neighbor Steve, a PhD engineer ex-patriot Brit and defiant leftist, helped MAGA Maniac Josh fix my malfunctioning headlamp, demonstrating that it’s easy to be enemies when separated by keyboards and easy to be friends when living side by side

Asbury Park Brewery is a local flavor that I was happy to support. No sign anywhere of Bud Lite or Budweiser anything, thankfully

Symbol of foolish National Park Service policies seeking to protect rare shore birds by excluding people from their habitat, but allowing artificially overabundant populations of nest-raiding raccoons and foxes to roam at will.

Beach goers nonetheless entered this area because there were zero nesting birds in it and there were literally tons of foxes running around in it. Come on National Park Service, you can do much smarter than this

1,000 welcome guests

Mark Twain noted that both guests and fish start to smell bad after three days. It’s a Mark Twain joke, not meant to be taken literally, wittily observing that well-intentioned hospitality has its natural limits.

A few days ago, I had a different experience with about a thousand guests, international immigrants, migrants, actually. Undocumented visitors, and formally uninvited to America.

For about three or four hours, I sat on the porch with a large coffee on one side, a pair of binoculars around my neck, and a large, heavy book on the other side. As I sat quietly, rarely moving and never moving quickly, I watched as a myriad of neotropical songbirds flitted, hawked, pirouetted, perched, sang, and chased all around the front lawn.

The green lawn is surrounded by a large mature hardwood forest with a high canopy, making it the natural destination for brilliantly colored migratory birds from as far away as Honduras and Guatemala. Gunmetal blue, electric blue, indigo, and boring old regular blue, scarlet, orange, red, yellow, grey, green, and just about every other color combination or version in the rainbow was represented in these tiny little bodies.

Tanagers, flycatchers, orioles (Baltimore and orchard), warblers in profusion, including the mysterious Cerulean Warbler, cedar waxwings, you name it, they were all there right in front of me.

If I had trouble identifying a bird, the binoculars were slowly raised to my eyes, trained on the little bugger, and I then engaged in a promiscuous amount of voyeurism. Reaching to my left for the big Smithsonian Birds of North America book and quietly turning its well-worn pages would usually reveal what I had seen and did not know.

Oh sure, there has been an ongoing battle with a female Phoebe the past three years. She likes to make her mud-and-sticks nest on the frame ledge above the front door. Her construction methods may be fascinating, but her habits are messy. Muddy gravel splashed all over the door, the windows, the porch. Then there are the kids, the poops, and of course we cannot disturb them, so we have to go around and use the back door. Last year she prevailed and caught me at a time when I was less vigilant. Grudgingly I allowed her to sit on her completed nest above the door, and aside from the mess and the Do-Not Disturb sign there, we were rewarded with close-up photos of the cutest little hatchlings and chicks you ever did see. We got to watch them fledge, too.

This year I chased her away and I think she took up a lesser spot in the pavilion, where she alternatively gave me the hairy eye from a perch, and then bombarded the truck daily with her droppings.

Another tiny bird provided a different interaction. Whistling his own song back to him from my front row seat on the porch, I called in a scarlet tanager who perched in a young white pine about thirty feet away, and inspected my odd appearance; I was found to be definitely NOT mate-worthy.

The pleasure gleaned from this quiet, near-motionless, but nonetheless intensely active time is tough to quantify. It is a special and rare time, snuck in during a narrow window in Nature’s endless timeframe. I can say that my heart sang along with those little survivors of journeys thousands of miles long, that my spirits were lifted with each visual treat they provided by wing or by perch, or by song, and that my own singular frustrations were slowly washed away by participating in something much grander, much more important than one man’s concerns:

That deep, quiet, often nearly invisible but enormous and magical ebb and tide of living things across the planet and through our lives. Gosh, are they all magical and their processes are magical, too.

This is a feeling of smallness, completeness, an unusually peaceful sense of place and order that is much more difficult for some of us to find in everyday human life. And yet it is the “natural world.” Think about that! Does it mean that we are living un-naturally?

For hunter-gatherers of old, seeing migratory songbirds probably meant berries and fruits were on their way, and that the known but unidentified Vitamin C in them would replenish the humans’ bodies after a long and planned near-starvation winter period. That is, this incredible migration so many tens of thousands of years old must have had a deep and more specific meaning to our primordial ancestors. Food.

But for us “civilized” people, quiet time, a time and place to contemplate, reflect, and to think is food. Brain food, emotional food, necessary.

Little migratory birdies, you are welcome back to America any time, with or without identification. I hope I get to see you all many more times again in the coming years.

Bear and Deer Seasons in the Rearview Mirror

The old joke about Pennsylvania having just two seasons rings as true today as it did fifty years ago: Road construction season in the Keystone State seems to be a nine-month-long affair everywhere we go, a testament to how not to overbuild public infrastructure, if you cannot maintain it right.

And the two-week rifle deer season brings out the passion among nearly one million hunters like an early Christmas morning for little kids (I doubt the Hanukkah bush thing ever took off). All year long people plan their hunts with friends and relatives, take off from work, spend lots of money on gear, equipment, ammunition, food, and gas, and then go off to some place so they can report back their tales of cold and wet and woe to their warmer family members at home. These deer hunts are exciting adventures on the cheap. No bungee jumping, mountain cliff climbing, jumping through flaming hoops or parachuting out of airplanes are needed to generate the thrill of a lifetime as a deer or bear in range gives you a chance to be the best human you can be.

Both bear and deer seasons flew by too fast, and I wish I could do them over, not because I have regrets, but because these moments are so rare, and so meaningful. I love being in the wild, and the cold temperatures give me impetus to keep moving.

One reflection on these seasons is how the incredible acorn crop state-wide kept bear and deer from having to leave their mountain fortresses to find food. Normally animals must move quite a bit to find the browse and nuts they need to nourish their bodies. Well, not this year. Even yesterday I was tripping over super abundant acorns lying on every trail, human or animal made.

When acorns are still lying in the middle of a trail in December, where animals walk, then you know there are a lot of nuts, because normally those low-hanging fruits would be gobbled right up weeks ago.

After still hunting and driving off the mountain I hunt on most up north, it became clear the bear and deer were holed up in two very rugged, remote, laurel-choked difficult places to hunt. Any human approach is quickly heard, seen, or smelled, giving the critters their chance to simply walk away before the clumsy human arrives. All these animals had to do was get up a couple times a day, stretch, walk three feet and eat as many acorns as they want, and then return to their hidden beds.

This made killing them very difficult, and the lower bear and deer harvests show that. God help us if Sudden Oak Death blight hits Pennsylvania, because that will spell the end of the abundant game animals we enjoy, as well as the dominant oak forests they live in.

The second reflection is how we had no snow until Friday afternoon, two days ago, and by then we had already sidehilled on goat paths, and climbed steep mountains, as much as we were going to at that late point in the season. With snow, hunting is a totally different experience: The quarry stands out against the white back ground, making them easier to spot and kill, and snow tracking shows you where they were, where they were going, and when. These are big advantages to the hunter. Only on Friday afternoon did we see all the snowy tracks up top, leading over the steep edge into Truman Run. With another two hours, we could have done a small push and killed a couple deer. But not this year. Maybe in flintlock season!

And finally, I reflect on the people and the beautiful wild places we visited.

I already miss the time I spent with my son on stand the first week. He was with me when I took a small doe with a historic rifle that had not killed since October 1902, the last time its first owner hunted and a month before the gun was essentially put into storage until now.

And then my son had a terrible case of buck fever when a huge buck walked past him well within range of his Ruger .357 Magnum rifle, and he missed, fell down, and managed to somehow eject the clip and throw the second live round into the leaves while the deer kept moseying on by. When I found my son minutes later, he was sitting in a pile of leaves where the deer had stood, throwing the leaves around and crying in a rage that we needed to get right after the deer and hunt them down. The boy was a mess. It was delightful to watch.

I miss the wonderful men I hunted with, and I miss watching other parents take their own kids out, to pass on the ancient skill set as old as humankind.

It is an unfortunate necessity to point out that powerline contractor Haverfield ruined the Opening Day of deer season for about three dozen hunters by arriving unannounced and trespassing in force to access a powerline for annual maintenance in Dauphin County. We witnessed an unparalleled arrogance, dismissiveness, and incompetence by Haverfield staff and ownership that boggles the mind. I am a small business owner, and I’d be bankrupt in three days if I behaved like that. Only the intervention of a Pennsylvania Game Commission Wildlife Conservation Officer saved the day, and that was because the Haverfield fools were going onto adjoining State Game Lands, where they also had no business being during deer season.

Kudos to PPL staff for helping us resolve this so it never happens again.

Folks, we will see you in flintlock season, just around the corner. Now it is time to trap for the little ground predators that raid the nests of ducks, geese, grouse, turkey, woodcock, and migratory songbirds. If you hate trapping, then you hate cute little ducklings, because the super overabundant raccoons, possums, skunks, fox, and coyotes I pursue eat their eggs in the nests, and they eat the baby birds when they are most vulnerable.

PSA: Please Keep Pets Inside

A pet is an animal that lives in a house.

Pets that are allowed to run freely out the front or back door, to cavort, chase, defecate, and frolic off its owner’s property and in Nature’s wide open beauty, are by definition feral.

Once out of the house or off the leash, these feral animals become capable of great destruction and usually accountable to no one. They also can easily be eaten by other feral animals and by coyotes, foxes, owls, and hawks. Or hit by a car.

Cats and dogs can get into traps set for fox, raccoon, coyote, and other furbearers.

Some of these traps merely restrain the animal by the foot. They do not break bones or cut skin. But other traps, like Conibears, will crush whatever sets them off, including a cat’s body or a dog’s face. If this possibility bothers a pet owner, then think of your animal’s safety, and do not let it run on someone else’s property; keep the pet under control at all times.

Audubon International estimates that feral cats alone wreak terrible destruction upon native songbirds, already under pressure from excessive populations of raccoons, skunks, and possums, killing hundreds of millions of colorful little birds annually.

Feral dogs bite people, chase wildlife, and poop on others’ property.

In most states, a dog seen chasing wildlife is subject to immediate termination. In fact I lost my favorite pet, a large malamute, after he broke out of his one-acre pen and a local farmer witnessed him gleefully chasing deer. Months later the farmer deposited the dog’s collar and name tag in the back of our pickup truck, told my dad where the carcass was buried on the edge of his field, and walked away. I was already heartbroken, but what could we say? Our dog had broken the law.

No responsible adult allows a pet to become feral. When it happens, it means the owner no longer really cares about the animal.

If you are a pet owner, please show that you care by keeping the pet safe inside your home. Everyone will thank you for it, especially your precious animal friend.