Posts Tagged → field note

This day a year ago while trapping: Cat up a tree!

Cat Up a Tree!

Text and Photos by Josh First (copyrighted)

I dislike trapping in rainy conditions, because it is uncomfortable, messy, and technically difficult, due to trap sets needing constant fixing up; and I really dislike processing muddy critters. Mud-covered fur is time consuming, and usually it is not worth it in my tight schedule. So from 2018’s trapping season opening day in late October, I waited six weeks, until a brief rain lull in mid-December, to put out some carefully planned traps.

Though I was aiming mostly for canids like fox and coyote, both bobcat and fisher were a reasonable hope. I have caught bobcats in and out of season in the past, but never a fisher. These are two neat animals worth working hard for, and each of which will quite willingly enter baited cubbies where foot hold traps can get some shelter from rain and snow.

So on the Wednesday afternoon before that Saturday bobcat and fisher opener, a half-dozen footholds (cubbies and flat sets) and a few large cage traps were set in strategic places near where I had seen fisher tracks or bobcats across a 100-acre area of mixed farmland and woods in Dauphin County. Bait is used in the cage traps to pull in the inevitable and limitless possums, skunks, and raccoons, so that, hopefully, only the cool critters find the footholds. And both bobcats and fishers will enter cage traps, so they do serve double duty.

One pass-through pee post set was put in a location where I have previously caught coyotes, foxes, and raccoons. It is at a corner of a dirt farm road, a woods road, a hay field, and brushy-hedged crop field where heavy woods meets an active agricultural area. Just about every local furbearer walks the brushy area, this road, and the field edges leading to it.

Coyote pee and coyote gland lure were put on top of a two-inch-thick dry pine limb sticking up 14 inches, placed at the seam where the goldenrod meets the farm road. A few pieces of goldenrod stem on the other side created the pass-through effect, so the animal’s body would line up with the hidden trap just exactly so. About eight inches away from the post an offset MB 550 attached to an eight-foot heavy chain linked to a heavy two-prong coyote drag was bedded level atop soft goldenrod tops to protect the trap from freezing to the wet dirt underneath, then covered judiciously in waxed dirt, then finished with more soft goldenrod tops and weed tips blended on top. The trap was perfectly “blended in” and hidden from sight.

The chain was stretched out away, into the reverting goldenrod field, and well covered and camouflaged with weeds, and the rusty-brown colored steel drag itself unobtrusively hooked into the dirt. With four heavy swivels well spaced between the trap and the drag, I felt confident that whatever would step on the trap pan while passing between the weeds to smell the pee post would commit its full weight, and be safely held fast, no matter where it went afterwards. I expected the animal to head directly to the nearby brushy hedges, where the grapple and chain would immediately become entangled, thereby holding the animal for the next 24-hour trap check.

Usually predators take a couple days to fully investigate my traps, and when setting this on a late Wednesday, I anticipated catching something in one of the sets on Friday night/ early Saturday morning. Though aiming for a bobcat, fox, coyote, or fisher, the truth is I had put off trapping so long that season that I would have been happy to catch just about anything.

The next day, Thursday, I did a cursory trap circuit check in my truck, looking out the window while driving past set after set. “No…No…No…footprints all around but no step on the pan…no…no…nothing” as I went by each trap location.

Pulling up to the pee post set, my eye was immediately drawn to the pee post itself lying on the ground, though the trap bed itself did not appear disturbed. Usually the post is knocked over by the chain after an animal has stepped on the trap and fled. So I got out to check, and was not surprised to see the drag gone. Following an obvious path of bent weeds and scuffed dirt leading away towards the closest brushy forest edge, my eyes naturally looked along that edge for a hung-up drag and critter.

With my hands on my hips, I stood and kept scanning the brushy woods-field edge. I was unable to locate anything, and felt mystified about how the critter could have escaped beyond such a thick, natural entanglement area. Mystery remained until a hiss to my right reached my ear, steering my eyes in that direction.

“Why is that long-legged grey fox up in that honey locust like that?” was my first thought.

Then another thought followed the first: “Why does that grey fox look like a big cat?”

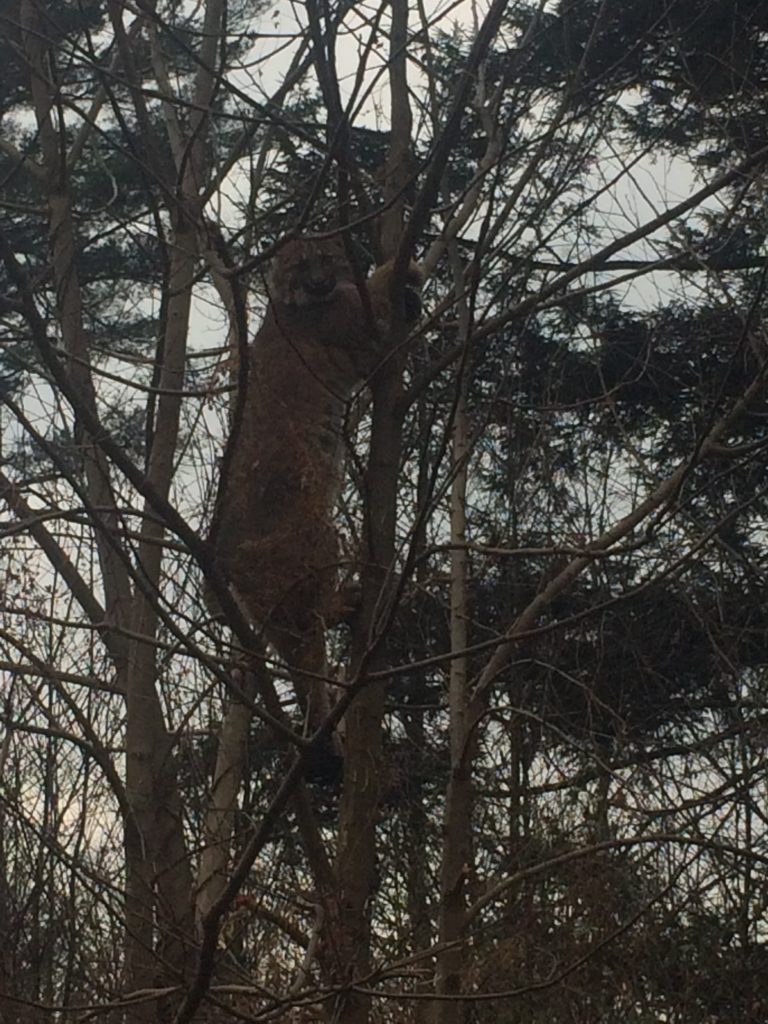

And then the bobcat came into focus. It was a nice sized young male, probably 25 pounds, about six feet up in a young honey locust, a tree that has plenty of sharp thorns and very hard wood. The drag was just touching the ground, and the chain was wound about the lowest branches.

OK, I thought, I’ll have this resolved in a few minutes. Seemed like no big deal to pull down the cat, use the catch pole to hold it steady while I released the trap from its foot and let it go unharmed.

Fast forward an hour, and each time I had tried different ways to bring it down out of the tree unharmed, the cat had moved farther up. With bobcat season two days away, by law the cat had to be released, but I was unsuccessful with each solution I tried.

Fretting and scratched by the locust thorns, I left, did some work, and returned a few hours later, hoping the cat had climbed down and was entangled in the ground brush nearby. On the ground it would be easy to release using a catch pole. Easier than up that tree!

But when I got back, the bobcat was still up the tree, and climbed yet higher as I approached it.

Time for Plan B, which is where I admit that I need help. Usually takes me a long, long time to implement Plan B, and so I called the Pennsylvania Game Commission southeastern regional office. At first the dispatcher congratulated me on catching the bobcat, but then moments later expressed his sympathy for me having to release such a fine trophy, as the season was yet to begin. He forwarded my message to a local Game Warden, who then fairly quickly met me right at the honey locust. In fact, he arrived so quickly that I could not help but wonder if he had been watching me the whole time, either chuckling at my clumsy efforts, or waiting to see what else I might do, or both.

“Thank you for coming. When my kids were little, their favorite book was Cat Up a Tree! And here it is in real life. Should we call the fire department?” I said to Game Warden Scott Frederick, half-jokingly. In that colorful book, the fire department saves the day by saving the cat stuck up in the tree, and we (and how I so liked the ‘we’ part) did indeed have a daggone cat way up in a tree. But unlike the book, we had no long ladders, or hero firemen, by the honey locust tree that day.

I asked my wife to film our escapade, but under questioning I revealed that pretty much anything could happen to anybody around this, so she said something like “No, I’m not recording two idiot men playing with matches.” I think her imagination had the warden and I emerging from the dense, high brush scratched head to toe, our clothes in ragged tatters, like some cartoon involving the Looney Tunes Tasmanian Devil. She wanted no part of it. This is why women live longer than men.

Warden Frederick tried to the untangle the chain and reach the animal, but with each new inch of loose chain, the bobcat sensed freedom and used the slack to climb ever higher. Upon reaching a tight chain again, he would stop his ascent, alternating between hissing at us and letting fly with whatever he could rustle up in his bowels. I came to learn that bobcats have an impressive amount and array of bad smells stored inside them. Neither Warden Frederick nor I smelled peachy at that point, but I gave in and laughed at him when he really got it good from the cat.

Eventually we had tried and tried every which way to get the cat down unharmed, the day waxed late, and so we decided that if the cat would not come down, then the tree had to come down.

A honey locust is a hard, tough tree, a pioneer species with twisting grain and sharp hooked thorns. Oftimes while being sawed, they don’t fall the way you think they will. In addition to its loud scary noise, a chain saw would remove too much wood too quickly to allow us to fully control which way the tree would fall, and a hand saw was too slow. So we used an axe to drop the tree, one carefully placed chop at a time. This gave us the best control over the tree’s slow descent, but it was sweaty work, and directly beneath the bobcat. So I let Warden Frederick do it.

Meanwhile, the bobcat climbed to the very top of the tree, clinging like a lookout in a ship’s crow’s nest, and swayed to the rhythm of the chop-chop-chop below.

As the tree gave way to the axe and slowly sank to the ground, the bobcat sensed its getaway approaching. But Warden Frederick was waiting with a catch pole. While I wish I had some humorous Game News Field Note material here to describe what happened next, the truth is Warden Frederick properly and quickly looped the bobcat’s shoulder and neck, under the armpit, thereby safely pinning the animal to the ground without risk to its esophagus (cats have really weak throat areas and they must be handled carefully). I got some last quick photos, threw a blanket over the bobcat to calm him down (the bobcat, not Warden Frederick), and then easily pulled the trap off of its foot.

Both of us inspected its foot and leg for damage, and seeing none, I stepped back, pulled the blanket, and the catch pole loop came off the bobcat. As many other trappers have experienced when releasing a trapped bobcat, this one sat on its haunches and hissed at us. He thought he was still stuck. Eventually he turned and fast- walked into the brush.

“Well, that’s it, I’m now officially jinxed, or ‘lynxed’,” I said to Warden Frederick. “From here on out I will catch only possums and skunks for the rest of the season.”

And in fact, for the rest of that epic rainy trapping season, such as it was, I caught a grand total of just five possums, one skunk, and one raccoon. It was my worst trapping season, numbers-wise, in many years. But in hindsight, it was also pretty rewarding to watch the Game Warden work like that. Both hard and smart, I mean. Citizens don’t get to see our public servants perform these kinds of feats very often, and with a good nature to boot. So in that sense, I had a uniquely good season. Thank you, Warden Frederick. Now I can’t wait for mountain lions to move into Pennsylvania!

[Why do I trap? I trap to save ducklings, goslings, baby songbirds, nesting grouse, woodcock, and turkeys from an endless number of ground predators like skunks, possums, raccoons, foxes and coyotes, all of which continue to pulse out from suburban sprawl habitats in artificially high numbers. These artificially high numbers of predators do tremendous damage to ground nesting birds, and basically cars and trappers are their sole adversaries. So if you are against trapping, you must hate cute little ducklings. Foothold traps do not crush bones or kill animals, they simply hold them, and as we can and did here, animals can be released from footholds totally unhurt]

If you ever want to feel like you are getting your tax money’s worth, look closely at this photo of PA Game Warden Frederick chopping at that honey locust. Except that the PA Game Commission operates on hunting license fees, timber sales, and natural gas leases! No tax money goes to the PGC, and yet they provide so many taxpayer services.

The four swivels and the long chain are visible here. The swivels prevent the chain from binding as the animal moves around, which gives the animal complete 360 degree movement. This is important so the animal does not torque its leg or hurt itself trying to get free. The long chain is needed to get hung up quickly in brush

The unharmed bobcat can be seen hissing at Scott, who has the catch pole loop around its upper body, pinning it to the ground. After taking this picture, I threw a blanket (Scott’s, not mine) over it to calm it down, inspected its leg for any damage, and when we each determined the animal was not hurt, Scott then released it. Using a catch pole on a bobcat requires getting the loop under its armpit and around the neck, so the esophagus is not damaged.

Field Notes

Field Notes are the monthly notes written by PA Game Commission wildlife conservation officers, about notable experiences and interactions they’ve had on the job, out in the field. And you know that for those folks, men and women, out in the field is truly out there in the wild. Their descriptions of encounters with people and wildlife are unique and often funny.

Field Notes are published monthly in the PGC’s Game News magazine, and for all of my hunting life (1973 until now), one person really summed up Field Notes and gave them pizzazz, making them my first-read in the magazine.

That was artist Nick Rosato, whose funny illustrations in Field Notes came to epitomize and symbolize the life and lighter side of wildlife law enforcement. Rosato’s humorous, rustically themed sketches summed up a WCO’s life of enforcing the law against sometimes recalcitrant bad guys, while maintaining an empathy usually reserved for naughty school children, when first-time offenders were involved and a slap on the wrist was needed.

Rosato died this summer, and his art will no longer grace the pages of Game News. I will miss Rosato’s humor and skill, because for most of my life he helped paint the human dimension of officers who are too often seen as gruff, grumpy, and unnecessarily strict law enforcers.

Speaking of WCOs, a couple years ago I was hunting during deer rifle season when I encountered a WCO I knew. He had a deer on the back of his vehicle and we stopped to chat and catch up with each other. Out of nowhere, I asked him to please check me, as in check my license, my gun, my ammunition.

Getting “checked” by WCOs and deputy WCOs is a pretty common experience for most Pennsylvania hunters, but the truth is, I have never been checked by anyone in my 42 years of hunting.

“Sorry, Josh, I just do not have the time. You will have to wait ’til later or until you meet another WCO out here,” he responded.

With that he smiled, waved, and drove off to follow through on his deer poaching investigation.

I think that encounter should be a Field Note, Terry. It is probably a first.

Maybe this year I will be “checked,” but perhaps having every single license and stamp available to the Pennsylvania hunter, and hunting only when and where I am supposed to hunt, somehow creates a karma field that makes WCOs avoid me.

Speaking of hunting experiences, yesterday morning Ed and I were goose hunting on the Susquehanna River. Out in the middle of the widest part, we were alone, sitting on some rocks, chatting about our families, professional work, politics and culture, religion. Our time together can best be summed up as “Duck Blind Poetry,” because it ain’t pretty, but it is soulful. Two dads together, sharing life’s experiences and challenges, makes hunting much more than killing.

While we were noting the Susquehanna River’s recent and incredible decline in animal diversity, we suddenly saw four white Great Egrets fly across our field of view, followed by three wood ducks. Intrigued, we began speculating on where they had all been hiding, when out of nowhere a mature bald eagle appeared on the horizon. It flapped its way over us and clearly was on the hunt. So that was why the other birds had quickly flown out of Dodge!

Seeing these wild animals interact with each other was another enjoyable example of how hunting is much, much more than killing.

Unfortunately, during that serene time afield, I introduced my cell phone to the Susquehanna River, and have found myself nearly shut off from communications ever since. While the phone dries off in a bath of rice, I am enjoying a sort of enforced relaxation. Please don’t think my lack of responses to calls and texts is rudeness. I am merely clumsy. Let’s not make that a Field Note.