Posts Tagged → deer

Some wonderful people gone

Jokes abound about aging, and quite a few are about those friends and family members who do not age with us, but who leave us all as we continue our own trajectory. Well, I am now definitely in the “aging” category and I am increasingly surrounded by people I enjoy and love who suddenly depart from this life. Recently two people here in Pennsylvania have left us all, and moved on to the spirit world, who I would like to mention. And it’s no joke, this dying thing. No matter what age a person is when they depart this life for the next, there is nothing funny about it.

Except maybe the last day on earth of European-Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, whose wild and often debauched Marxist Bohemian lifestyle made for intriguing movies and books. While some or maybe even a lot of the facts of Frida’s life may be funny depending upon the person considering them, her actual physical departure from this planet really is funny. I think.

After Frida died relatively young from cancer, or whatever it is that eventually afflicts the heavily debauched, her friends had her corpse dressed beautifully in her most customary colorful and flamboyant way, and prepared themselves all for a formal cremation send-off party in whatever crematory was present in Mexico City at the time. Her friends gathered in the crematory room while Frida’s corpse was ceremoniously loaded into the burn chamber, and as the roaring natural gas flames came to life, they all raised their glasses and toasted Frida.

And then the room erupted in gasps, cries, and people running for the exits, because suddenly Frida’s corpse stiffly bent at the waist, sat up, and made a wicked grin as her abundant hair caught on fire and created a demonic flaming halo around her yet untouched face. She wasn’t actually gone!

Yes, this was all her body’s muscular reaction to the sudden burst of 2,000-degree heat enveloping it, but apparently if you knew Frida, you kind of didn’t expect her to just die, you know, lie still and never move again. And indeed, she had lived up to all the hype about her, even while lying quite dead in the cremation chamber. I think this true story is funny, even though I did not know Frida and was not present at her cremation.

What is not funny and yet is not unexpected is the recent departure of Jim Brett, of Lenhartsville, PA, which for our geographically challenged readers is just north of I-78 and just south of Blue Mountain in Berks County, PA. Still confused where Lenhartsville, PA, is? OK, yes, it is the equivalent of East Succotash, PA, Nowheresville, PA, etc., and it is just about next to Hawk Mountain, the internationally famous sanctuary devoted to conserving birds of prey, especially on their annual migration south. There, solved this location question for you.

Hawk Mountain started as a simple land purchase to keep the shotgunners from standing on Blue Mountain’s highest Tuscarora sandstone boulder ridgetop and mindlessly swatting down out of the sky nearly every raptor that flew by on its way to South America. And in short order, more land purchases were added to what is now called the Kittatinny Ridge migration corridor. Hawk Mountain eventually became an educational organization and a destination for birders.

In the 1930s, birds of prey (hawks, owls, eagles, kites, vultures) were considered pestilential nuisances to farmers’ chickens and the rabbits and pheasants hunters enjoyed pursuing. In time, around the 1930s, raptors gradually became understood by some Americans as an important part of a healthy and properly functioning ecosystem, just as balanced populations of wolves, bears, mountain lions, bobcats and fishers have been subsequently understood today.

Hawk Mountain is now the world’s oldest continuously functioning conservation organization, but from 1934 to 1966 it was kind of a hidden gem, a hole in the wall of Blue Mountain that only certain initiates knew about or appreciated. It became much better known and more widely appreciated and much visited after Jim Brett became its second “curator,” as the chief executive position there is uniquely called.

As its leader, Jim Brett elevated Hawk Mountain to international status, built lots of buildings, hired lots of staff, attracted a lot of visitors, raised a lot of money, and he became a leading voice in bird conservation around our little blue and green planet.

On the outside, Jim Brett was a colorful Irishman, full of naughty jokes and a singular ability to imbibe liberally (often of his own make) and then hold forth to a captivated audience about biological and ecological science. But because Jim’s mother was Jewish, he had a separate interest in Israel, which, because it sits on a physical crossroads, is a lot like Blue Mountain. Israel is a birding Mecca.

A “sh*t ton” as Jim would say of raptors, storks, and other incredible and rare bird populations migrate through Israel, and Jim made their conservation from one end of their migration to the other one of his life’s missions. His Jewish half worked well with the Israelis, and his Irish half worked very well with the surrounding populations. One of his crowning achievements was working with Yossi Leshem to resolve bird strikes on Israeli fighter jets.

By finding ways to greatly reduce large rare birds being suddenly introduced to fighter jets at 1,000 mph, Yossi Leshem & Co. were able to save the lives of said rare birds, said giant titanium war eagles, and unsaid but implied young fighter pilots. It really was one of the great wild birds-living-with-modern-humans conservation success stories.

I met Jim Brett in 1998, when I had started working at PA DCNR in Harrisburg (having fled the corrupt and destructive US EPA in Washington DC). He was giving a presentation at an environmental and conservation education conference in Harrisburg, PA, and as the DCNR director of said polysyllabic educational field, it was my duty to both speak and to listen. Jim was standing up on the stage showing ancient stone tool artifacts and explaining the nexus between primitive hunter-gatherer lifestyles and the conservation or decimation of wildlife. I was hooked immediately.

Jim and I maintained a close personal and professional relationship until Fall, 2009, when I ran in a congressional primary (I was prompted to run by the devoutly corrupt and evil Manchurian Candidate Barack Hussein Obama, then president for nine months). My expressing my long quietly held political views educated not just Jim, but a sh*t ton of my “friends” and fellow conservationists alike about my true self. Gasp. Turned out that Jim did not know how conservative I was, and I did not know how liberal Jim was, and despite my desire to remain close, Jim had a hard time with it.

After 2009, our relationship involved less and less personal time, and fewer phone calls. I still have a generous gift that Jim gave me, which I occasionally take out and look at, admire, and then put it back in its safe place.

Jim and I stayed in touch through mutual friends for many years, including those who went on his African safaris he led. I can still recall Jim describing the funeral rite for a young son of a Maasai tribal leader, which he witnessed some time in the 1980s, I think: The boy’s body was ritually washed and then slathered in lamb fat, then put in the chieftain’s hut. The entire village was then evacuated and moved to an entirely new location, where a new settlement would be constructed. After the hyenas had entered the old village and consumed the boy’s body, the entire place was torched and left to become natural ecosystem thereafter.

Jim’s bright blue eyes flashed as he told this story, as indeed one would expect from someone so in tune with the endless hidden vibrations of our magical natural world. Though I know his spirit is now soaring with the majestic raptors, I doubt Jim’s liver will ever go the way of the hyena, Frida, or any mortal flesh for that matter. His official obituaries are here and here.

A second loss is someone I knew less closely, but with whom I shared a great deal in common and with whom I filled my buck tag this season: Phil Benner of Liberty, PA.

Until he unexpectedly died of Covid several days ago, the incredibly physically fit Phil Benner was a devoted father, a devoted husband, a devoted brother, a devoted uncle, a devoted son. He was a hard working small business owner, a risk-taking entrepreneur, and a pastor who saw God and felt Him deeply in the natural world around him, including the leaves rustling in the winter tree branches, and the quiet tinklebell sound of a small mountain stream’s clear waters falling over boulders. He appreciated everything and took nothing for granted.

Not only will I miss Phil Benner, the world will miss Phil Benner, because the world needs a billion more gentle, charitable, loving, devoted, kind, tolerant, peaceful Phil Benners. His loss is huge.

Phil Benner and his son Nate with a large bodied six point buck taken in Pine Creek Valley in late November, 2023

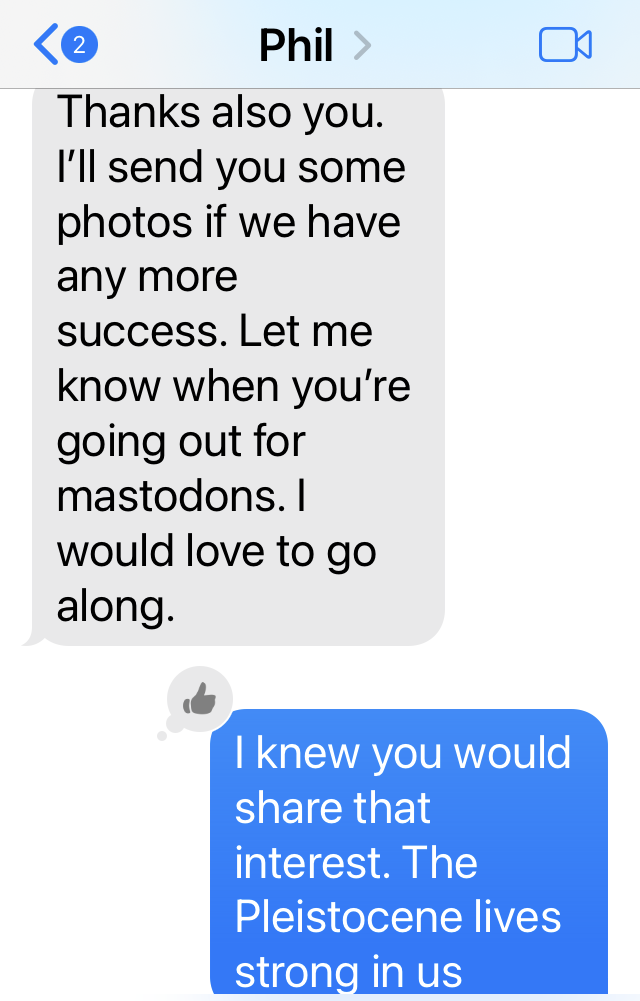

Book review: Secrets & Science of Primitive Archery

Ryan Gill’s book, The Secrets & Science of Primitive Archery, is a must-have for all stick bow hunters. You cannot find your way in the dark without a light, and this book is the illumination every traditional and self-bow hunter needs. I don’t care how long you have been hunting with your Osage orange self-bow or even a traditional bow by a small maker. If you hunt with something that does not have training wheels, then you need this book.

I must admit that I am almost ashamed it has taken me over a YEAR to review this book. Actually almost two years. Author Ryan Gill deserves much better treatment for all the hard work he put into this book. What can I say, Ryan. America has had a lot of ups and downs since 2021, and for political watchers and commenters like me, practically every day has felt like an all-hands-on-deck. All the political stuff has taken up the blog space. I am sorry, buddy. Hopefully I finally give you and the excellent book your due here.

As a traditional archery hunter since I was about fourteen, I have been enamored of bows made of a simple stick and a string. When us kids made our own bows out of saplings we cut in our woods (fifty years ago…), we would tie on a piece of baling twine and shoot arrows made of tree branches, goldenrod, whatever we could get our hands on, and practice with what we had. As the years went past, some of us were gifted compound bows, and others got simple recurves. I got a recurve, and some pretty sorry secondhand Easton aluminum arrows, to which I attached basic Bear broadheads.

If I had a nickel for every deer I collected hair from, I would have enough to buy a malted milkshake at the Lewisburg Freeze, which was fifty cents way back when, and costs five bucks now. That is to say, I never killed a deer with a bow, but missing didn’t stop me from trying.

Fast forward and I had my own kids, all of whom enjoyed shooting little fiberglass kid bows. When the boy attained the age of about seven, he demanded a “real bow,” and so off to the Eastern Traditional Archery Rendezvous we went. There we located a nice faux curly maple kid recurve with about 20 pounds of pull. Enough to skewer a squirrel or ball up a bunny in the back yard, which the boy kept after. Many years later we would go back to ETAR to get his real Big Boy bow, a reflex-deflex by the Kilted Bowyer. At 43 pounds pull weight at 26 inches, this is a true hunting machine, pretty, yes, but in all the clean simplicity a true bow should have.

But in between the little boy bows and the last big boy bow there were a lot of experiments over the years. Saplings cut, strings attached, arrows made, trials run. Like I did when I was a kid fascinated with the basic but powerful physics of archery. And this is where Ryan Gill’s fascinating book enters the picture.

Ryan Gill came to our attention by his YouTube videos. Because we were naturally looking for information about what we were doing right and doing wrong. Ryan doesn’t just cut saplings, attach a string, and shoot some crappy home made arrows. Au contraire! Ryan makes all kinds of powerful self-bows from all kinds of different woods, including Osage orange, hickory, black locust, and others, that will kill deer, bear, wild hogs, and even huge bison. And then Ryan strings the bows with real animal gut. And then he makes real cane arrows, tipped with real flint and chert heads that he himself knapped. Talking the real deal here. And through it all in his videos and his book, Ryan explains how primitive archery really worked tens of thousands of years ago, and how it can work really well for us today.

I learned a lot from this book.

Because I am a numbers guy, Ryan’s statistical analysis of his different bows, using different strings (animal and plant fiber), using different arrow shafts (river cane, wood) etc, really speaks to me. He does a great job of tabulating his data, which, when all his testing is said and done, tells us exactly where to go: Osage orange bow stave that is dried daily, using either a modern bow string or an animal gut string, and shooting properly made river cane shafts fletched with goose feathers and tipped with the proper and surprisingly small stone arrowhead, that go at least 130 feet per second, with 150 fps or better being the best and most likely to catch an unaware deer standing flat-footed.

If you are at all a traditional or aspiring primitive archery person, you need this book. This is a must-have resource that you will find nowhere else. It has an incredible amount of fascinating and directly applicable how-to information to every step and facet of primitive and traditional archery, as well as the historic and anthropological background to how primitive archery evolved. I read it twice before I felt qualified to write about it here, and I highly recommend it.

Welp…there is always the late deer season

The 2023 deer hunting season is probably going to be remembered in most parts of Pennsylvania as a strange time. For reasons already written about here previously, the deer just have not been available to the hunters in ways and numbers that hunters are accustomed to. On properties I hunt all over Central PA, deer were either invisible or invested with magical disappearing powers. Everywhere I am familiar with, the deer moved up hill, as far away from human activity as possible.

To say many hunters are frustrated is a big understatement.

All I can say to all this bad luck is that at least we have the upcoming late flintlock and archery seasons to try to make up for the low productivity of our regular season. And in at least one area designed to reduce Chronic Wasting Disease, DMAP 6396, we have a continuation of rifle season for antlerless deer only until late January. I intend to take a new rifle afield for that season in that area.

Folks, for the next ten days, practice, practice, practice with your flintlocks. My biggest challenge with flintlock hunting is the huge flash going off in my eyes. Once I get used to that, I am deadly steady with the old smoke pole. Probably takes me ten to twenty flashes to begin staying stone cold steady.

Late last year after a bunch of really lame close-range misses, I began practicing shooting my flintlock rifle with only priming powder in the pan, and nothing loaded in the barrel. Repeated trigger pulls with explosive flashes in my face helped me overcome my natural reaction of flinching and pulling my head back and away from the flame. Needs no explanation that moving your head off the gunstock is going to ruin your accuracy and aim, which means you probably won’t hit what you thought your gun was aimed at.

Ah yes, the well-earned moniker “flinchlock…”

Couple of recommendations: Go high up, because that is where most of the deer are, and try to hunt in groups, either as actual drives or as organized approaches to hunting the same area together.

Remember to go afield with a brand new sharp flint on your gun. If you take the old, dull flint that you have been practicing with this year, you stand a good chance of hearing “klunk” when you pull the trigger as the rounded flint then hits the frizzen without any sparks, and thus yields no primer ignition, and thus there is no ka-boom coming out the end of your gun barrel.

Though quite often the deer will be fascinated by the weird klunk sound, staying riveted in their spot staring intently in the direction of that odd sound. You might get a second or even a third trigger pull during this stare-down period.

Good luck, folks! Shoot straight and walk tall.

Do deer processors give you back your own deer?

Pennsylvania rifle season for deer is nearing the end of its second and concluding week. On average, Pennsylvania hunters annually kill 400,000-500,000 deer, and I would just hazard a guess that 2/3 of those carcasses are taken by the hunter to local deer processors.

Tonight, deer processors across Pennsylvania are working triple-staffed and double overtime to process the hundreds of thousands of deer being brought in by successful hunters.

A perennial question asked by both new hunters and well seasoned is “When I pick up my deer from the processor, will it actually be my deer I am getting, or will it be someone else’s deer?”

There are two certain answers to this question, and I base these on my own experience and the experiences of many friends and acquaintances.

First answer, Maybe. Depending on what you want done to your deer, you might get back 100% of your deer or you might get back 75% of your deer, with the 25% difference being parts of other people’s deer. If you just want real simple cuts, basic steaks from the backstraps and the hams, and roasts from the neck, leg, and shoulders, then you stand a better chance of getting your deer back. This is because it is almost as easy for the processor to cut your deer up into these basic cuts with a bandsaw and a boning knife as it is to grab whatever oddball cuts he has on hand to fill your order.

Second answer, when ordering sausage and hamburger, is absolutely No. This is because deer sausage, pepper sticks etc. are made from various trimmings and random pieces of deer as they are brought in from the very beginning of the archery season, based on the kind of demand that processor has experienced in the past. Additional batches of sausage are made as demand increases towards the end of archery season and into the rifle season. There is just no way that your deer can be turned into its own sausage mix. Your deer might be contributed to a big pot of deer trimmings destined for sausage, and you might be getting your portion of that sausage, but that sausage just isn’t going to be yours and yours alone. It will be a mix of various deer brought in the same time as your own.

I cannot tell you how many times I have gone through the expense of having my prize deer turned into beautiful shrink wrapped cuts at a processor, only to discover that the cardboard box I received my order in is short at least ten to fifteen pounds of venison (from a huge buck). And worse, some random pieces have been thrown in a try to make the balance, as the processor guesses it. And some of the packages have been frozen a long time. And the same cuts of meat are colored differently, as though from different animals.

The truth is that if you want to eat your deer, then you must either butcher your deer yourself, or get together with buddies and butcher all of your deer together.

Butchering a deer by yourself is much easier than most people think, especially if you are willing to cut up the backstrap and hams into basic steaks, and then grind up everything else for hamburger or sausage. In fact, I am about to take a deer I shot today over to a friend’s house where we are going to butcher it in his garage. This is going to be his first experience doing this, but I am sure it will not be his last time.

With buddies, you can pool your odd trimmings and leg meat for sausage. One or two guys or their wives run the sausage/ hamburger grinder and filler, and by the end of the weekend the sausage has been cooked/smoked, and everything is all done simultaneously. I have seen a historic hunting camp in Elk County that had the most impressive kitchen and butchery set-up, including scales for weighing both the whole deer and the various parts and cuts. This is nice so that the guy who shoots a 60-pound yearling gets his deer, and doesn’t unfairly get a bonus pay-out taken out of someone else’s 120 pound deer. Unless this is the way everyone agrees to work together: Everyone goes home with more or less the same amount.

Nothing against the deer processors, they have an important role to play. But the question asked in the beginning can only be satisfactorily answered by doing the job yourself, and I can say from long experience that butchering a deer is easy and gets faster and easier the more experienced at it you become.

Ok so how is your deer season going?

You wait all year for these two weeks of rifle season in PA, and then after a restless night the opening morning arrives. Five days in, and hardly a shot heard each day, no deer seen, hardly any sign encountered, and you are wondering what the heck is going on.

Don’t sweat it, you are not alone. You are in very good company. A lot of Pennsylvania hunters are grousing to each other tonight about not seeing any let alone many deer so far, not getting shots at deer, not even finding sign of deer, like poop or tree rubs. Not even hearing shots. Apparently Wisconsin is also seeing a real drop in their deer harvest in firearms season, too.

Something is amiss, especially in the Big Woods, no question.

Are we witnessing some mass die-off from disease, like Chronic Wasting Disease, or Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease? It is possible, but I have not yet seen any deer skeletons lying randomly in the woods. Maybe they are out there and I just haven’t found the graveyard yet. In 2005 northcentral PA had a huge deer die-off from late season snow and ice that made the mountains impassible. The deer could neither walk on the surface for weeks, nor could they dig through the compacted ice and snow to reach food. We did encounter random deer carcasses everywhere during the spring that year.

Maybe black bears ate more deer fawns than we anticipated (I witnessed a large black bear catching, killing, and eating a young deer this May, which is cool). Same can be surmised for coyotes, which are renowned deer eaters. After several years of purposefully hard harvests, there are now fewer bears in PA, by design, and theoretically less bear depredation of fawns in 2023. But there does seem to be an awful lot of coyotes. Everywhere.

Up north, we have no acorns to speak of. Late spring frosts killed our acorn flowers a couple years in a row, and gypsy moths have been terrible year after year. Any acorn flowers that survived spring frosts were eaten by the gypsy moths, whose egg masses are visible everywhere up here. So there is very little to no food in the Big Woods, and as a result, most wild animals seem to have flown the coop. Bear hunting last week was impossible. And so far this week, deer hunting has been tough.

Yesterday I was fortunate to set up in a natural funnel and catch two does transitioning from feeding areas to bedding areas. And today, with the help of friends on a small and carefully targeted drive, I filled my buck tag. Based on what I am hearing, I am incredibly lucky this year. Most hunters are struggling just to see deer tails bouncing off into the distance.

So if you are one of the PA hunters who is feeling dispirited right now about the apparent evaporation of deer this season, here is my best advice: Go hunt places you don’t normally hunt, and where you think others probably don’t hunt often, either. Steep hillsides are great locations for hiding deer. Play the wind, keeping it in your face as much as possible. Go slow, and quiet. And have a friend or two join you for a two-man push or leap-frog, or a two-man push with one stander. And then the stander becomes a pusher and the former pushers take up stands.

Remember that whitetails like to loop around behind their pursuers. If one guy is pushing and another guy is quietly lagging behind a hundred yards or more, he has a good chance of getting the deer that snuck off and went around the pusher. Again, make sure the wind is in your favor (blowing from the deer to you, not from you to the deer), and be as quiet as possible.

Switch up your game this season, because it seems that just sitting and waiting for animals to come out and present themselves broadside is not happening a whole lot in 2023. We gotta get in after them, and make our own action.

Good luck!

A simple request of PA hunters

A simple request for our Pennsylvania hunters: Be hunters, not assassins.

Relying on technology to obtain an animal whose senses you cannot defeat within fair chase distances because your hunting skills are stubby is lame. Killing animals from far outside their hearing, smell, eyesight is not hunting, it is just killing, an assassination. This is not fair chase.

If you are strictly subsistence hunting, I understand, but if you are adhering to fair chase and sporting chances, this long distance stuff ain’t sport hunting. It is ultra cheeseball. Yeah I know, this whole obsession with long range sniping and ultra accuracy that came out of our military experience in Iraq and Afghanistan is cool. But it is not hunting.

A person who is sniping wild animals at hundreds of yards has expended zero skill or effort to defeat the animal’s natural defenses. You might as well drop a hellfire on it from a drone. And yeah, there’s probably a lot of “gamers” who will claim that that also takes “skill” and is “hunting.” Stop it. You are debasing yourself with this crap. Pick up an open sighted 30-30 lever action and learn what hunting is again or for the first time. You deserve it, the animals deserve it, the sport deserves it.

Good luck out there this deer season.

Yeah, PA’s lame bear season in one picture

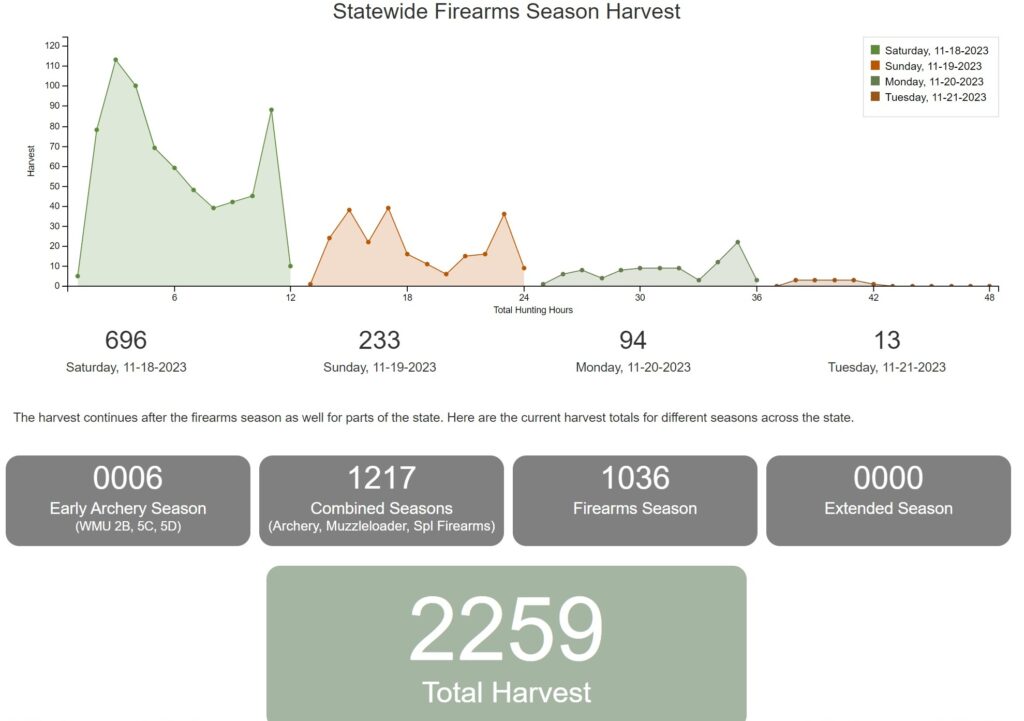

Pennsylvania is about to have one of its lowest bear harvests in decades. And like so many policies of any sort, the story of this failure is told not just by the data, but by a picture of the data (see below).

In sum, this year’s early bear seasons of archery and muzzleloader resulted in roughly 1200 bears being taken by hunters. These are predominantly individual hunters in elevated stands, not crews of drivers pushing bears to standers.

By the time the real firearms “bear season” arrives in late November, much of the steam has been bled out of the system, so to speak. The demand has been met. Many serious bear hunters have already taken their bear and they won’t be going “to camp” to participate in punishing bear drives through thick mountain laurel on steep mountains in the northcentral region. And when the most ardent hunters pull out of a camp, that loss of energy and excitement affects everyone else. We noticed many empty camps across the entire northern tier this past week.

Again, the 1,217 bears taken in the early season so far are 200 bears ahead of the roughly 1,000 bears on record for the “bear season” as of tonight, which is the end of the formal “bear season.” In other words, bear season wasn’t. It is actually producing behind the early season.

So is the early season the real bear season now?

Add a poor acorn crop to the situation, and whatever bears were roaming around in October’s early season have gone to den for the winter now in our “bear season,” or have moved southward by the time November arrives, because all of the available wild food has been eaten up. We are now in our third year of a failed acorn crop in the northern tier, and the silence of our woods shows it. No food means no wildlife. Hunters saw no poop, no deer rubs, no squirrels, no nothing. Hunters scouring rugged northern tier landscapes that are the historic high producers of bears are encountering woods devoid not just of bears, but of deer and turkey, as well.

Yesterday was a classic example of this dynamic. Our guys put on a drive across a NW Lycoming County mountaintop area that usually holds bears. I was the lone stander in the primo spot, a saddle between two hills with a stream running through. I could see far in every direction. There were no other drives happening anywhere around our guys, which is unusual. But another and much larger drive was going on behind me, and pushing toward the area we had hunted the day before. And half a mile down the forest road several long range hunters were set up looking across a canyon. If there were bears around, or even deer, the two drives would push them past the long range guys, at least.

And yet, by the time dusk arrived and our men had slid and tumbled down the mountain side to gather at the truck, no one anywhere had seen a bear or a deer, nor heard a shot. The long range guys were packing up as we were driving out, and they told us they had seen several deer on Sunday, but nothing else any other day, including that day that had so much activity.

The Pennsylvania Game Commission is a government agency, and agencies make mistakes. Sometimes the best-intended and carefully considered policies have unintended consequences. Maybe the Saturday opener (as opposed to the long-time Monday opener) to bear season is part of the failure we are seeing. Maybe it’s the acorn crop failure making a bad situation worse. Maybe it’s the early season stealing all of the thunder from the regular rifle bear season. I don’t know the entire answer why, but the numbers don’t lie, and this 2023 bear season was a flop. Yes, we will see another 100-200 bears taken in the extended season that is concurrent with deer season in some Wildlife Management Units. But overall, PA has not seen a bear harvest this low in a long time. And as I recall, last year wasn’t that great, either.

Something is wrong and something needs to change. A lot of small businesses in rural areas depend on these big bear and deer seasons to make their end-of-year financial goals. Let’s hope the PGC staff and the board are up to the task of fixing it.

Harvest results as of the last night of regular rifle bear season, 2023. Not final, but not going to change much. The early season was the best season.

PA’s 2023 bear season

After hearing just one rifle shot all day (followed by the customary follow-up shot thirty seconds later, and the coup-de-grace shot a minute later) today, at 4:20PM, I felt compelled to write about what seems to be happening this bear season. In a nutshell, this is not your pap’s or even your dad’s Pennsylvania bear season in Northcentral PA. That long-hallowed experience of buffalo plaid Woolrich coats and moldy little hunting camps built in 1948 filled with men putting on big drives across the landscape, is now a thing of the past.

Some people blame the Saturday bear season opener that started eight years ago for the demise. Others blame the early October muzzleloader and archery seasons. Either way, what many hunters are calling the death of the famed PA bear season is actually a direct result of the incredible success of PA’s decades-long bear population conservation program.

When PGC biologist Gary Alt became the steward of the PA bear program in the early 1980s, he faced a problem. Hunters, nature lovers, and simple habitat and ecosystem health required more bears across Pennsylvania. And bears were not responding to the demand. In twenty years of hard and smart work, Dr. Alt turned the situation completely around. When Dr. Alt left the PGC twenty years ago, his life’s work was one of the great wildlife conservation success stories in America. Black bears then filled habitat niches in almost every county from Philadelphia to Erie, from Honesdale to Pittsburgh, and everywhere in between.

And then, almost overnight it seemed, PA had way too many bears. Bears were showing up in cities proper, turning over trash cans in suburban back yards everywhere. And so the PGC had to try and dial back some of Dr. Alt’s success. Increasing the number of bears taken by hunters was the solution.

Now looking at harvest data resulting from a half dozen years of early muzzleloader bear season, early archery season, regular bear season, and extended bear seasons running concurrent with deer season, it is easy to see why we only heard one rifle shot all day today in what probably still is the epicenter of PA’s bear hunting. And why none of our guys encountered any bears hanging from hunting camp porches on their valley run tonight.

Early muzzleloader and archery seasons combined now account for almost half of the overall annual PA bear harvest, even before “bear season” has begun. These early season hunters are mostly single men hunting near their homes. By the time the traditional bear season arrives in late November, half the licensed bear hunters who are likely to kill a bear are already tagged out, and the rest are looking forward to the concurrent bear-deer seasons in their home hunting territories. Few hunters feel compelled to make the historic annual migration north, and why would they?

Those of us, we hardy few, who do still come to the traditional bear hunting ground up north, are faced with an already depleted bear resource, and many fewer men pushing across the landscape to break free and push those bears that remain. And yet, despite our reduced opportunity, we enjoy the crisp Fall air, the camaraderie, the laughs, and the naughty food and drink our wives would never approve of, if they only knew.

Good luck this season, boys. You’re gonna need it.

A fabulous hunting trophy

Another PA archery season over (UPDATE: No, it wasn’t over, I have not kept up with new PA archery season dates), another season I did not arrow a deer or a bear. It’s not that I could not have killed a buck with a gigantic rack, I could have, a hundred times. It is that I chose not kill him. He isn’t necessarily tame, but he has been hanging around an awful lot. It would have been easy to send an arrow or a bolt through him from a porch or an upstairs window. But in my old-er age, I must be turning soft-hearted. He even came into a ground blind I was in with a crossbow, and puttered around. I decided to admire him, instead.

Just seeing wild beauty like his brings me real pleasure. I don’t need to put his head on the wall for him to make me happy.

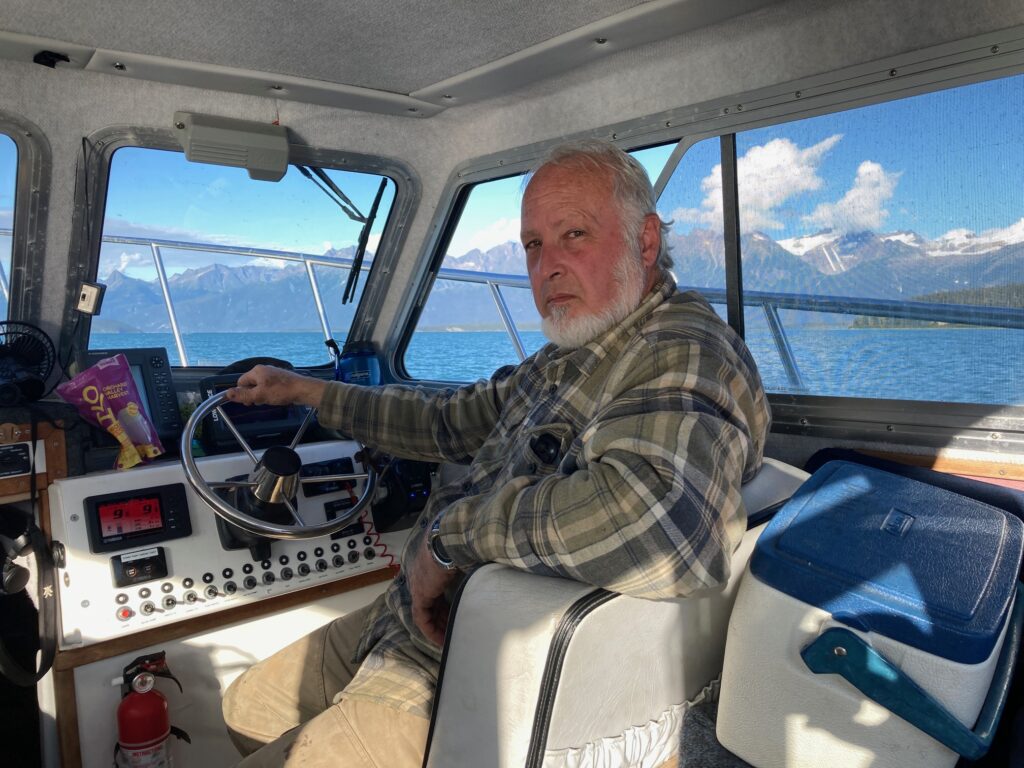

Even without killing a black bear or a wolf, I still got an amazing trophy from my Alaska hunt in September. And no, I am not referring to the beautiful stones and colorful pebbles I bring home with me as keepsakes from all around the world. Alaska streambeds were loaded with all kinds of incredible geological samples, and I could have easily filled a pickup truck bed with the easy ones. Instead, I picked up a memento of someone else’s kill, and brought that home with me.

While I was stalking a salmon stream in the northernmost part of southeast Alaska eight weeks ago, cradling a 45-70 rifle in my arms and looking for black bear feeding on spawning fish with one eye, or a wolf, and watching out for the ever-present brown bears/grizzlies with the other eye, I happened upon a scattering of big bones up against a stream bank. Bleaching white on the top side, and staining green with algae and moss on the bottom side, these bones marked a kill site. From what I could piece together, a two-year-old moose had made a stand against a pack of wolves or a large grizzly on this site, and had lost. It was right here where he had died and had been eaten.

One bone in particular caught my eye, the hip socket, sitting concave-side-up to the sky. What made this individual bone stand out so much was both how perfectly round it was, and yet how it was also framed on three sides by heavily fragmented and fractured ends of bone. Something really big had broken this heaviest of bones, and the tooth marks are still on the socket. As artists are fond of saying about something that catches all of the visuals just right, it was a study in contrasts.

I bent down, picked up the broken socket bone, brushed off the dirt and leaves, and stuffed it into my backpack among the long underwear and my PB&J sandwich. Back home in Pennsylvania, it was cleaned off, lightly bleached, and re-purposed into a pipe holder and ashtray. It is actually incredible how perfectly my tobacco pipe fits into that hip socket. Now I can use the bone as both an ashtray and a reminder of being in some of the world’s wildest country.

As soon as it dried, I sat down to enjoy a bowl of cherry cavendish, and with the light tobacco smoke swirling up around my head, I was immediately lost deeply in thought about God’s magnificent creation, the amazing wild beasts that have inspired us wee humans since our dawn here on Planet Earth, and how a hunting trophy is what you make of it. It doesn’t always have to be something you killed yourself. Sometimes it is just a small piece of the wilderness we love that serves as a symbolic touchstone and a time machine that transports us back to a place and time where all that mattered was the wind direction and the smell of Fall in the air.

Looking at this ten thousand years ago or fifty thousand, any Neolithic hunter anywhere around the planet would have felt exactly the same way. This one piece of fractured bone connects us two hunters across time, even though we never met.

A thousand overnight tragedies

Normally, the smell of rotting fish is a signal to clean out the fridge or to leave the area you are in. It’s a universally bad smell, and no one normal wants to be around it. But it was a pervasive good sign where I happened to be standing, because it was associated with the freshly dead salmon heads and remains at my feet that had not been here the previous afternoon. A thousand individual tragedies had occurred along this stream bank overnight, as bears had picked muddy bank spots to grab spawning salmon and take them uphill where they could eat them without the fear of being ambushed by humans, or bigger bears.

We had hunted and fished along a roughly seventy mile vertical stretch of southeastern Alaska for over a week, and in addition to beginning to smell a little fishy myself, I had also saturated and possibly satiated a cavernous need inside me. It is an ever-present deep, clawing need that most wilderness seekers share, be they bikers, hikers, canoers, campers, photographers, fishers or hunters. Sorry, I am not going to quote Thoreau or Muir or Roosevelt on the tonics, joys, highs, or benefits of directly experiencing wilderness. My own wilderness pleasure is gained from simply not seeing a single other human being (except my hunting/fishing partner, when I have one) anywhere near where I am hunting or fishing. That unusual moment results in me feeling like I have better than average odds of achieving my goal, because I have the whole landscape to play without intervention.

On this trip, my “public” goal was a wolf, a blacktail deer, and/or a big black bear better than 300 pounds. Hides and skulls alone were going to come home with me. Edible meat was going directly into my buddy’s freezer. All of the many salmon I caught on the trip went into either my buddy’s smoke house, into his freezer, or into my stomach. It pleases me to report back that chum (dog) salmon directly out of the ocean taste damned good. It is also a fact that chum salmon do not keep well overnight, and that even halibut turn up their noses at it. I suppose freshly caught chum can be immediately canned, but given that there are usually better alternative salmon species to eat and can, I don’t see why a person would make this choice.

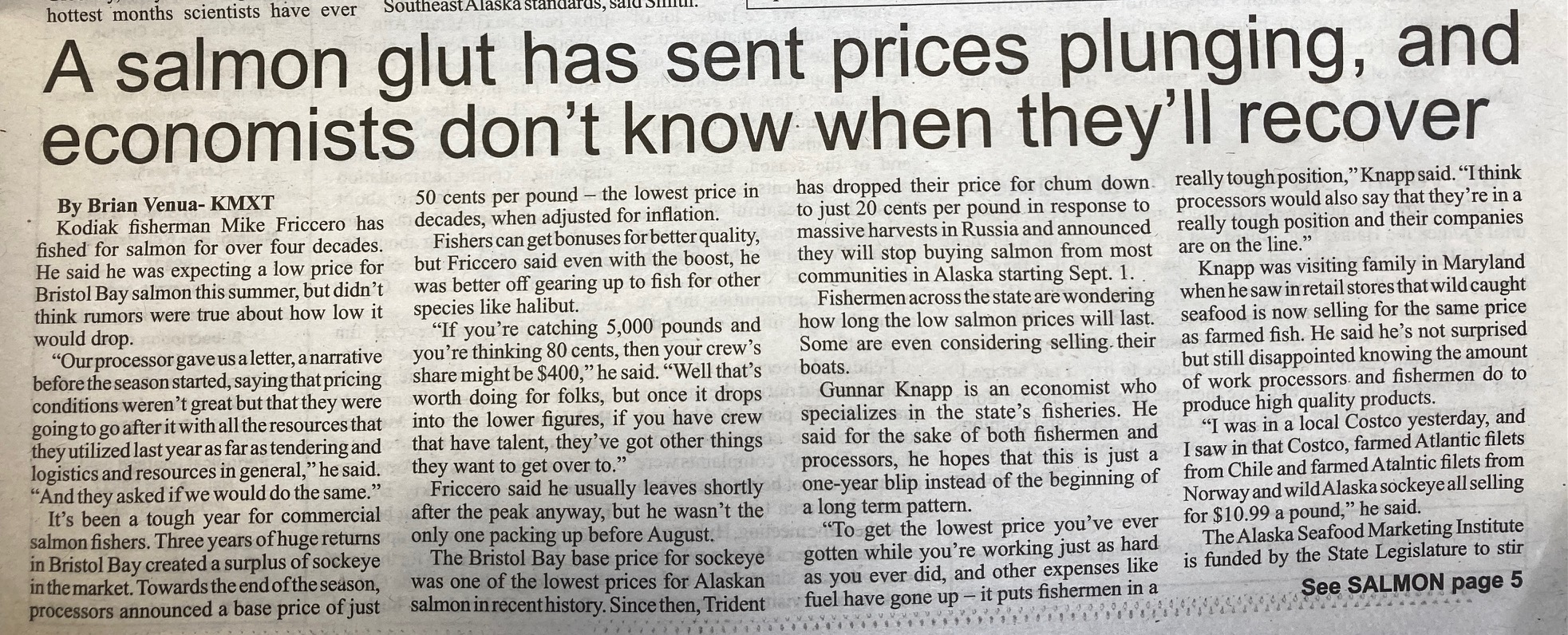

Incidentally, about those salmon: Alaska’s management of its salmon runs has been so good, so professional, so scientific, and so successful, that there is actually a glut of salmon in the streams and on the American market. Therefore, wild caught salmon prices are way down. A lot of commercial salmon boats were out netting, and the cannery we visited was in business, but with diesel fuel at about eight bucks a gallon there and salmon at eighty cents a pound, it’s hard to see how the netters will survive. But thanks to the Alaska Department of Fish & Game, the bears have plenty to eat before denning and hibernating for the long, cold Alaskan winter.

Goals are critical on a wilderness trip. Even stupidly simple ones. You have to have goals before you set out on a trip like this, or else you will wonder what the heck you were doing out there when you get back to civilization. My actual personal goal was simple: To fish and to hunt as much as I could, and this goal was easily met. On this trip, I was often able to do both hunting and fishing simultaneously: We slowly trolled salmon spoons behind the boat while glassing the shorelines for critters. A rubber dinghy towed in the backwash provided us the ship-to-shore transportation we needed. See a salmon stream that is calling your name? Go ashore and hunt it, and look for salmon-eating black bears to fill some tags; and look out for the griz. We saw a lot of griz.

Only saw wolf tracks in one very remote spot, and I passed up the one black bear I had a shot at. Only twenty feet across the salmon stream from me, he was either a genetic runt, an ancient-looking yearling, or maybe a female. Whatever kind of black bear he was, he was crabby enough to growl at me before shambling off to less crowded fishing spots. I wouldn’t shoot a bear that small in Pennsylvania, and I sure wasn’t going to fill my Alaska tag with it. Maybe I will go back for the spring bear hunt in 2024.

Despite fighting our way up into the interior of an island known to have blacktail deer, we saw none and feared the griz there more than we were willing to keep going after deer. Signs of griz were everywhere. I picked and popped high bush cranberry and high bush huckleberry while noting the increasing deer browse the farther in and higher I got. But it was a veritable jungle, and surprising a griz up here would mean my certain mauling, possibly my death, and so I decided to nicely frame my deer locking tag when I got home instead of risking life and limb to fill it. I headed back out and found Merlin asleep in the sunshine on the beach.

A loud thud on the bottom of the boat awakened me from my cramped sleeping position, and I rolled out of my sleeping bag onto the cabin floor, which was cluttered with gear and guns. Walking out onto the deck to look for the source of the thump, I saw a sea lion, a seal, and a pod of porpoises chasing salmon all around us in the early morning dimness. Mist rose from the water, and then the rosy tint of dawn’s first sunbeams lit up a nameless glacier high up in the crags across the water. I felt stoned on all this Mother Nature. Like I said, I was there just to hunt and fish, and whether or not I went home with the physically tangible results was not nearly as important as absorbing and sucking up the magic around me and filling that big, hungry, empty cavern in my soul. You just can’t have this magical experience without public lands, and some of that designated as wilderness. This, these, we had.

Alaskan salmon management has been so good that there are actually “too many” salmon, if there is such a thing

Reflected is the Chilkoot River, where we fished with the bears and a gaggle of international tourists following them up and down the river

Trolling spoons for salmon, towing our dinghy, and glassing the shoreline for critters. This is hunting and fishing at the same time

My hunting kit. A Henry 45-70 lever rifle (not crazy about the cheesy rear sight), a JRJ knife, rugged Leupold binoculars, home made dried fruit and jerky

Grizzly sow and cub eating salmon as they spawn upstream from the Chilkat River. I saw a lifetime supply of griz on this trip.