Posts Tagged → mountain

This hemlock log shows climate change

Climate change has been a normal and natural fact of life on Planet Earth since the planet was created. Volcanoes explode and the earth warms up as a result. Glaciers that build up covered entire mountain ranges underneath, then recede and create new mountain ranges, then melt again, and their flood waters created new rivers, several times. Pennsylvania’s Pine Creek in the “PA Grand Canyon” used to flow north into the Genesee River watershed, until a huge ice dam from the last glacial period melted, broke, and caused an enormous torrent of water to flood southward. In that brief moment about ten or twelve thousand years ago, naturally occurring climate change forced Pine Creek to flow south, where it has become a major tributary to the West Branch of the Susquehanna River.

Climate alarmism is quite another thing, a false thing, a made-up thing, a silly thing, a destructive thing, and it is ruining a basic scientific fact that should be easy to study and understand.

Climate alarmism is where political activists falsely claim that “scientists agree that humans are causing Planet Earth’s climate to change” and that all Americans and Europeans (not the Chinese or the Indians) must therefore make drastic changes to our lifestyles, to our diets, to our freedoms. This is a fake emergency, a fake crisis, designed to help political activists get political outcomes they can not otherwise get through the democratic voting process where informed voters choose elected officials and policy positions themselves.

To illustrate how climate change naturally occurs all on its own, I took a picture and posted it here. Below is a picture I took of a roughly 160-year-old hemlock tree that a logger I work with cut down in Clinton County, PA, a month ago. If we look at the growth rings in the base of this tree, we see clusters of rings that are very wide, where the tree grew a lot in one growing season (April – September), and we see clusters of rings where the tree grew very little in one season. What is really interesting about looking at tree growth rings is that we can easily understand the climate surrounding that tree at the time of each growth ring.

Wide growth rings are associated with both an open forest canopy and lots of sunlight reaching the tree, and also with years of plenty of rain and warm temperatures conducive to plant growth after the canopy has grown up and over.

Thin or narrow growth rings are associated with a dramatic lack of sunlight, a lack of water, and/ or colder temperatures.

As we can see from this picture, this 160-year-old tree has experienced several major climate shifts over its lifetime. Each colored box is a clump of similar growth rings, which represents a period of about ten to twenty years. See how this tree went for a decade or two subject to long stretches of either very wet and warm climate, or very dry and cold climate? And we know that this tree’s life experience was largely outside of the period where the climate alarmists say humans have had the greatest influence on climate.

This tree’s life, as we see it in its growth rings, clearly shows that northcentral Pennsylvania’s climate has naturally fluctuated on its own, with no meaningful human intervention, for a long time. The picture also shows that within periods of intense dryness, there were single years of abundant rain, and then the dryness returned for years.

Today, climate alarmists seize upon every dry spell, every rainy period, every storm, to falsely claim evidence of human-caused “climate change.” If what the climate alarmists say is true, then this poor tree has had both a schizophrenic life in a natural world where equilibrium is more the natural rule, and it also experienced a lot of human caused climate change while the planet had very few humans on it to affect the climate.

In other words, this tree shows that the climate alarmists are wrong. Really wrong. The trees don’t lie, but the political activists do lie. And that fact is alarming to me.

Hemlock log cut in July 2023, in Clinton County, PA. This tree has experienced widely varying climates over its long lifetime, especially while there were very few humans on Planet Earth. There is no such thing as human caused climate change. Environmental damage, yes, of course, but not climate change. Climate alarmism is a political claim, not a scientific claim.

PA elk & bear seasons now behind us

You can spend all year excitedly anticipating a few days here or there, and before you know it, those days arrive, they happen intensely, and then they are over like a dream.

This dream we speak of here are the various big game seasons that are such a big part of so many peoples’ lives, entire families and communities, entire businesses (I think hunting is an annual $1.6 BILLION business sector here in Pennsylvania). Thus far we have had an elk season and now the main bear season pass along. Here are some of my thoughts on these two wonderful experiences.

First, the elk hunt.

I was fortunate enough to draw a coveted PA elk tag, after applying for many years and building up a lot of preference points. The lottery drawing was announced in late August, and I immediately began planning. The general elk season is just six days long, and unless you are going to engage a guide for a few thousand dollars, you have a lot of work to do before setting foot afield with a gun. If you draw a bull tag, paying a guide is worth it.

After a tremendous amount of analysis and planning, and some September scouting, I was fortunate to hunt for elk with some good friends and a .62-caliber percussion rifle over my shoulder in Elk Zone 13. We camped out on a log landing in Sproul State Forest, with elk all around us, and each buddy scouted hard each day, looking for elk that the sole hunter (me) could get after.

Elk Zone 13 is huge, and contains a lot of vast public land. And so the elk harvest data shows that it is a bit of a Death Valley in terms of hunters actually killing an elk within it. While a lot of Pennsylvania elk hunting takes place briefly where a lot of the local elk have pet names and are used to being around people, there are a few elk zones where the opposite is the case. Zone 13 is one of those opposite cases. It is a tough place to hunt under any conditions, and under the rainy, warm, and very windy conditions we had, it was just about impossible. In the end, just one of three bull tags there was filled, and as of the fifth day of the six day season, just one of the six cow elk tags had been filled. I was not one of those people lucky enough to fill my elk tag.

And it was not a harvest failure because we didn’t hunt smart. We hunted so smart that we were bumping into elk guides and their clients at every turn. We had done our homework ahead of time, and we knew where the elk were likely to be, which is where you will find an elk guide, too.

One of the things I did as part of the analysis and planning phase was was plot all of the past elk harvest data on the large Elk Zone 13 map the PA Game Commission sent me. Once your eyes see exactly where the elk are killed every year, almost always in large clusters, over the past seven years that Elk Zone 13 has been around, you recognize where to concentrate your field scouting efforts. And then our subsequent field scouting efforts confirmed the presence of elk, including the day before the elk hunt started.

Like I said above, the weather conditions were awful for any type of big game hunting, and especially with a primitive weapon such as I carried. My effective range was 110 yards, and 75 yards was a lot more preferable. But range doesn’t matter if you can’t get an elk to stand broadside for a few seconds. I did mix it up directly with an elk herd that was hiding in a forest, and I did call one close back to me, and I did get a couple good setups on moving elk. But the seesawing winds gave away my presence each time, and the elk stormed off each time. Like I said, I had a wonderful time with good friends in a beautiful place with a fantastic gun over my shoulder. Elk or no elk in the hunting bag, I had a great time hunting elk in Pennsylvania (an especial Thank You to the many private landowners who generously granted me access to their properties to hunt elk).

Now, bear season.

Bear season ended yesterday, and the last of the bear hunters grudgingly left the cabin today. As usual, we had a large crowd gathered here, with everyone happy to catch up with chums from years past, sharing good food and good drink and good cheer. One thing all hunters eventually begin to notice is that with age comes a mellowing of the spirit. The chase is not as important as simply being present in God’s creation, often communing with Him in the largest house of prayer anywhere, the mountain forest cathedral.

And so fewer and fewer guys are coming here to hunt, and more and more guys are here to relax. And that is OK.

We who both communed with God in the mountain forest cathedral, and who also hunted, saw no bears and only a few deer. Mostly because there are no acorns in the woods, and all wildlife must go where the food is. If there is no food here, there are no bears here. Gypsy moths devastated Pennsylvania’s oak forests this past summer, and so there were no oak flowers to turn into oak acorns to fatten up buck and bear, squirrel and turkey. The woods was totally quiet this week, and it made me wonder what a squirrel migration looks like. Do hordes of mountain squirrels move en masse into suburban yards in lean years like this one? And where the heck do all the bears hibernate?

Roughly 1,450 bears were killed in PA’s early archery and muzzleloader seasons, and so far just under a thousand bears total are reported for this week’s bear rifle hunt. Usually this week’s four-day hunt results in an enormous bear kill. We are now looking at an epically low bear harvest in a state with a huge and burgeoning bear population that needs managing (Just a few days ago New Jersey issued an emergency bear hunt approval, because The People’s Republic of New Jersey is being overrun with bears, which unfortunately cannot be trained to eat liberals but whom the liberals recognize as a natural predator and are seeking to reduce out of self defense).

Another thought a lot of people are sharing today is that the early bear seasons, archery and muzzleloader, are very effective, so that come the late November bear season, there are a lot fewer bears to be had. Bears that are facing both extreme hunger AND extreme hunting pressure will den up early to get out of the storm. It seems a lot of the bears that survived the early seasons arrived in a bleak foodless November and said an early good night until March, 2023.

Next up is deer season, another dream time. And our deer patterns are also all off kilter here, so it is going to be a very interesting deer hunt in the mountains. Again, it’s no acorns, no deer. Except for that one gigantic buck I saw a couple times….stay tuned for that report. Let’s hope it makes up for the no elk and no bear reports we already filed away for 2022…

An 1884 double rifle made for tigers in India would be great bear medicine. If only a bear would appear.

This remote old mine is one of dozens that dot our mountains. It is a fine place to hunt, take a nap, or write in a notebook. A couple times I have done all three in one visit.

Camped with friends on an old log landing in the Sproul State Forest is a wonderful way to spend life’s limited time, elk or no elk in the bag.

A great way to spend a day hunting elk, with a beautiful .62 caliber rifle (not a smoothbore) made by Mark Wheland here in PA. With its 335-grain round ball, it is easily capable of cleanly taking a hearty elk.

Reflections on 2020 bear season

As if by magic or just the batting of an eyelid, the much anticipated 2020 bear season is now behind us, having concluded at dark yesterday. Sad to see our friends go; we had such a fun time! The last of our bear hunting guests have left, cleanup has commenced, preparations are under way for Thanksgiving, and there are some reflections to be had on bear season.

First, where the hell were the bears? Serious question here. We hunt in a mountainous Northcentral area that is Pennsylvania’s “Bear Central.” And despite us daily scouring a lot of remote, very rugged territory that is usually home to lots of bears, we saw neither bears nor bear poop. None. It could be the warm weather has bears hunkered down under cool overhangs in even more remote places. It could be the low acorn crop has bears going in to hibernation early, because there is no more food for them to eat to put on the extra fat they need to hibernate successfully. The truth is, no bear tracks or poops have been seen around here for months, which is remarkable. I cannot think of any year prior like this.

Second, where were all the hunters? We heard only a few shots between Saturday and Sunday, and either none or one on Monday, and for sure none on Tuesday; and very few hunting parties were on the radio on any day. This means that few large scale hunting drives were going on. Without hunters moving across the landscape, the bears don’t have to move out of their way. They can just sit still and not run the risk of exposing their rib cage to a hunter’s bullet. That means that the bears can loaf about in some remote corner, escaping the unseasonable warmth or just waiting for the wafting human scent to drift away before making their usual rounds again. Which means the few hunters who are out don’t see much action.

Third, where were all the other critters, like turkeys and deer? Like with bears, we saw very little deer or turkey poop in the woods. And although I myself saw two whopper bucks and a five-point up close, no one else saw any deer. Nor did any of us see any turkeys. Once again, the absence of these otherwise ubiquitous animals could be due to the relative absence of acorns. Which would push the wildlife far afield to find food sources.

Fourth, despite all of our hunting setbacks, did any of us care a bit? No! We missed all of our friends who could not be with us for various reasons, like fear of the CCP virus, or family emergencies requiring them to stay at home. But those of us who gathered had a lot of fun nonetheless. And with or without a bear on the game pole, we would not have missed this time together for any reason at all. We caught up on our families, our work, our homes, cars, friendships, wives, and politics (yeah, there was a lot of pro-Trump politics). Some people drank way too much alcohol, and we got some great pictures of it all, like the one guy asleep on the cold ground outside. No, we don’t post those here. We ate like kings, that is for sure, and no one lacked for food or drink.

Finally, it is possible that the new early bears seasons (archery, muzzleloader, and special junior+ senior rifle) are removing so many bears from the woods that come rifle season, very few huntable bears remain to be had. According to real-time hunting harvest data posted at the PA Game Commission website, more bears were killed in the early seasons than in the official rifle season this year. This means there are fewer bears available for the rifle hunters. It is possible that many hunters expected this, based on last year’s harvest patterns, and they stayed home or hunted alone, instead of joining the big crew at camp, like usual. As of late today, just 3,138 bears had been killed total this year. That is about a thousand fewer than expected.

Based on this raw data alone, the early bear seasons are actually backfiring. They are not removing the high surplus number of bears that are beyond Pennsylvania’s social carrying capacity. Rather, the early bear seasons are removing the easiest bears and leaving few to be hunted in the later rifle season.

And this new dynamic could be the real story in PA’s bear season: There are so many early season bear hunting opportunities for individuals that they collectively take the wind out of the sails for the regular season hunters, thereby having a boomerang effect on the entire thing and limiting it.

We won’t know what all this data really means for another few years, and by then either great or even fatal damage will have been done to Pennsylvania’s traditional bear camp culture, with its big gatherings and big drives and big camp camaraderie dying out, or we will simply all have to learn to adapt to new ways of hunting. I have to say, there is no substitute for men gathering at a camp to hunt together. The gathered hunting party is the most human of experiences; it is an institution as old as our species. Its purpose was not just making meat, but also social and sociological.

I sure hope these myriad new early bear seasons are not self-defeating, in that they do not kill that traditional bear camp culture by removing its whole purpose ahead of the game. Question for the PGC: What incentive is there to push your body hard through rugged and remote landscapes, destroying your boots, tearing your clothing, and often losing or breaking some of your gear, including damaging your gun, when the animal you are seeking has already been removed?

Below are some photos from one of our trail cameras two years ago. Just days after bear season ended, a bear was caught gloriously and most joyously rubbing its back against a young white pine tree. Almost like a pole dancer. Pretty hot hip shakes there. We haven’t seen a bear anywhere around here since May this year.

When one of our guys is finally browbeaten into washing dishes after years, it is cause for “Notify the media” acts like taking his unhappy picture. This is back in 2015. He still has to be browbeaten into washing the damned dishes

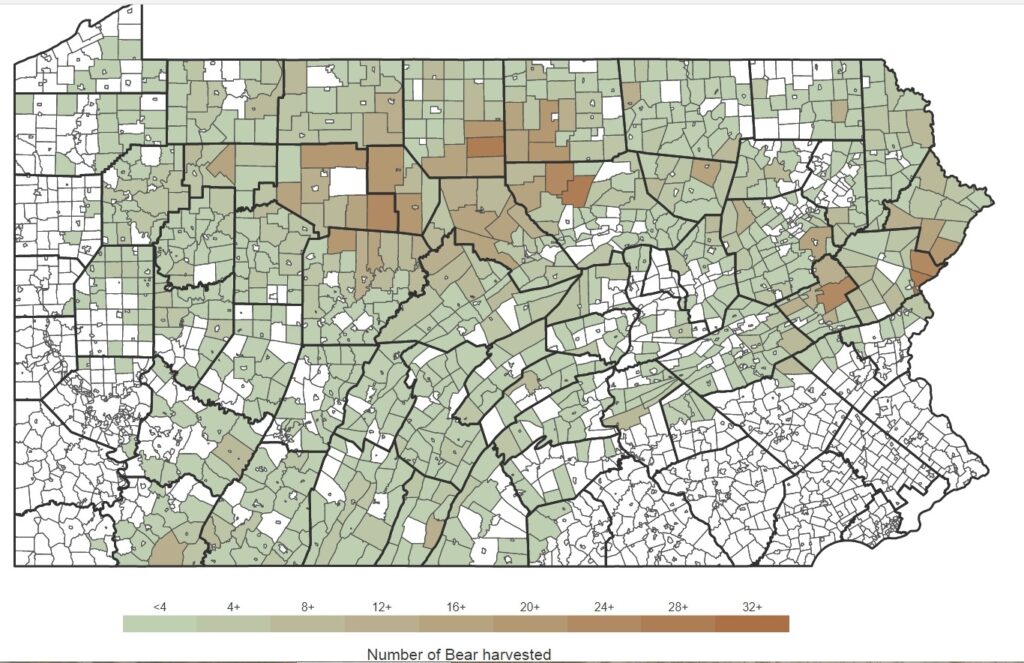

Lycoming County is the boot-looking shape in the northcentral area. Its northwestern corner is where we hunt. The darkest township there demonstrates the importance of organized hunting drives. A bunch of large hunting clubs are located in this area, and their members put on highly coordinated, obviously successful drives.

Father’s Day

Today is Father’s Day, the day we celebrate our dads, the people who helped us grow into young men and women. For thousands of years, fathers have been the protectors and providers for their families, and they have traditionally been the source of life-saving wisdom and decision making. The lessons and skills they teach their children, especially their sons, are essential for living life properly.

Thank you to my dad, for teaching me to use a chainsaw and an axe from a young age. For giving me the childhood chore of splitting and stacking firewood all summer long, so that our family would have heat and comfort all winter long. Other chores included weeding the garden and shooting pests like chipmunks, squirrels, and groundhogs, all of whom could easily do tremendous damage to the garden in just minutes. And while these chores trained me in self-reliance, hard work, and planning ahead, it was the one thing that dad would not let me do that probably shaped me the most.

Although my dad comes from a hunting family, he himself did not and still to this day does not hunt. Oh, he appreciates wild game and will eat it over everything else, given a choice. But when I started taking my BB gun on deer hunts with neighbors at age eight, my dad always told me I had to get close to the animal to shoot it. As I grew into a young Indian or frontiersman out there in the wilds of southern Centre County, I was prohibited by dad from topping my rifles with scopes. Only open sights were allowed. He said using only open sights taught me woodcraft, requiring me to get close to the wild animals I wanted to harvest, before taking their lives.

“It is only fair,” he said. “You can’t just assassinate unsuspecting wild animals from hundreds of yards away. If you hunt, you must be a real hunter. You must get close and take the animal with skill, on its own terms, where it can see, hear and smell you. That is fair.”

And so last deer season, on a steep hillside deep within the Northcentral PA state forest complex, all of those lessons and preparation came together in one quick, fleeting second. I did the Elmer Fudd thing all alone, quietly sidehilling into the wind, trying to live up to Dad’s dictum. One cautious, slow step at a time. Eyes scanning ahead, downhill, and especially uphill. Ears on high alert for any sound other than the wind in the leaves. Big bucks that are bedded down high above where the puny humans might slip, stumble, and walk, are most likely to flee to higher ground when one of us Pleistocene guys shows up too close for comfort. Deer might hear or smell us coming a long way off, or they might see us at the last second because we are being quiet and playing the wind right, but they know that within a hundred yards or so, we can kill them. So they flee uphill, and in stumbling up against gravity and slippery things underfoot they give us shot opportunities we would not otherwise have.

And so when the strange <snap> sounded out ahead of me, just over the slight rise that led into the large bowl filled with mature timber and rock outcroppings, and an odd looking animal bolted down hill almost bouncing like a fisher, I quickly backpedaled.

Anticipating where the deer would emerge about 130 yards below me, I quickly and also carefully walked straight backwards to where a natural slight funnel in the ground provided a clear enough shooting lane down through the forest to a small stream bed. Anything passing between me and the stream would be broadside at moments, providing a clear shot through heart and lungs if I took careful aim.

And sure enough, the big doe filled one of those spaces so briefly that I don’t even recall seeing her. All I do recall is how the rifle butt fit carefully into the space between the backpack strap over my shoulder and the thick wool coat sleeve, and how the open sights briefly aligned with her chest. The thumb safety had been snicked off already without thinking, and the gun cracked. I fired the gun instinctively.

Quickly raising the binoculars to my face, the doe was clearly visible way down below me, lying fully outstretched on the forest floor just above the stream bank, like in mid-leap with her front hooves and rear hooves completely extended ahead and behind, except she was not moving. She was laying still, her neck fully stretched out on her front legs like she was taking a nap. I watched her tail twitch a few times and then knew she was dead.

Sliding on my butt down to her was more challenging than climbing up to where I had been still hunting her. Northcentral PA mountainsides are the most difficult terrain for humans, in my experience. It is topped with a layer of slippery leaves, then wet twigs and branches waiting underneath to act like oil-slicked icicles, ready to throw a boot way ahead of one’s body. If the wet leaves and branches don’t make you fall down, then the rotten talus rock waiting underneath the leaves and twigs will slide, causing you to either do an extra-wide wildly gesticulating split, or fall on your butt, or fall on your back.

So I scooted downhill to the doe, tobogganning on my butt on the slick forest floor, cradling the rifle against my chest, keeping my feet out ahead of me to brake against getting too much speed and hurtling out of control.

Arriving at her body, I marveled at how she resembled a mule. Her long horse face and her huge body were anything but deer-like. Her teeth were worn down, and she must have been at least five years old. The single fawn hanging around watching me indicated an older mother no longer able to bear twins or triplets. This old lady had done her job and had given us many new deer to hunt and watch over many deer years.

Normally, in such remote and rugged conditions I will quickly bone out the deer, removing all of the good meat and putting it in a large trash bag in my backpack, leaving the carcass ungutted and relatively intact for the forest scavengers. But this doe was so big that I just had to show her off to friends, and so after putting the 2G tag on her ear, I ran a pull rope around her neck and put a stick through her slit back legs, and began the long drag out.

This hunt has stayed with me almost every day since that day. I think about it all the time, because it was so rewarding in so many ways, and emblematic of being a good hunter. Not the least of which was the careful woodcraft that led up to the moment where the smart old doe was busted in her bed and then brought to hand with one careful shot as she loped away, far away. Just as easily I could have been a hunter clothed in bucksin, using a stick bow and arrow five thousand years ago.

Thanks, Dad, for all the good lessons, the chores, the hard work, the restrictions and requirements that made me the man I am today. Without your firmly guiding hand back then, I would not be the man I am today. And what kind of man am I? I am a fully developed hu-man; a competent hunter with the skill set only a dad can teach a son, even if it takes a lifetime.

[some will want to know: Rifle is a 1991 full-stock Ruger RSI Mannlicher in .308 Winchester with open sights. Bullets in the magazine were a motley assortment of Hornady, Winchester, and Federal 150-grain soft points, any one of which will kill a deer or a bear with one good shot. Binoculars are Leupold Pro Guide HD 8×32 on a Cabela’s cross-chest harness. Boots are Danner Canadians. Coat is a Filson buffalo check virgin wool cruiser. Pants are Filson wool. Backpack is a now discontinued LL Bean hunting pack, most closely resembling the current Ridge Runner pack. Knife is a custom SREK by John R. Johnson of Perry County]

How to properly pronounce “Lancaster” and why it matters, here

“Lan—Cas–Ter.”

When I heard the radio ad with that unnatural, long, drawn out pronunciation of the county and city just south of me, the endless chasm between the syllables felt years apart, so unnatural that my internal warning system flashed “outsider alert, outsider alert.”

This ear-grating goofball advertisement played for two days before being pulled and replaced with the same voice, but subsequently correctly saying “Lancaster” as almost one long syllable.

How many calls and emails did the radio station get about this? Evidently enough to make an impression on the people in charge of advertising. Running a radio advertisement that annoys the audience is counterproductive, and you’d have to hear from a large enough segment or sample of that audience to get the message that your message was not just falling flat, but actually bothering your target audience. People cared enough to contact the radio station and voice their opinion.

Why do Central Pennsylvanians care about how their locations are pronounced?

Probably for the same reason that Perry County has communities like Newport and Duncannon and New Bloomfield housing most of the county’s 30,000 citizens, and yet those same people will tell you they are from Perry County. Not from Newport, New Bloomfield, or Duncannon. This is because the identity of the locals in Perry County, and elsewhere around the Central Pennsylvania region, is one of community, togetherness, joined together in common interests and identity. Not separated from one another, as in most other places. The larger community, like the county, is the defining characteristic for the residents. We all belong here and we belong to each other, in common and shared purpose.

I recall reading a linguistics study of Central Pennsylvania years ago, and how the authors traced the unique accent here to Swiss and German immigrants in the 1700s. And in fact, if you talk to older old order Amish and some older old order Mennonites, you will indeed hear that very distinct English spoken with some sort of heavily foreign accent. Like all languages, including British English, Southern drawl American, Ebonics in the ‘hood, and so on, this common sound is the sound shared by a commonly identifying group of people. When they hear the familiar pronunciation of their own language, they know they are communicating with someone who is “one of us.”

One of the defining characteristics of Central Pennsylvania is its pretty resilient regional identity, including political views and political engagement, religiousness, and so on. Outside forces may be at work here, altering our beautiful landscape with criminally ugly warehouses and temporarily bombarding our ears with Flatlander-foolish pronunciations of our local places, but through it all, we still hold on to our common identity, our common purpose, our common interests.

Central Pennsylvania is still one big community with common identity. This is one of the reasons that the Obama Administration targeted Lancaster County (and rural Minnesota) for simply air-drop dumping huge numbers of fresh foreign immigrants, most of whom could neither speak nor read English, but who had been carefully instructed how to vote for the “(D)” on the ballot. Politicized efforts to disrupt traditional American sense of community and togetherness, and common purposes and commonly held interests and values, are increasing, as one political party in particular attempts to destroy and re-make America into an identity-less, gender-less, Constitution-less, all-powerful big government global nerve center for everyone on the planet and every cockamamie idea that will destroy “evil” capitalism etc.

And this is why people here so strenuously resist the improper pronunciation of “Lancaster.”

This mispronunciation concretely represents the outside evil forces arrayed against our traditional identity and lifestyle. When we reject that pronunciation, we are asserting our identity and rejecting outsiders, carpetbaggers who attempt to sell us snake oil without even taking the littlest amount of time to understand our closest held thoughts and beliefs. And they fail to do that because they simply don’t care about us or our religious redneck identity; and, in fact, they look down on us.

For all you outsiders, for the record, here in Central Pennsylvania we pronounce Lancaster as one long, fast, single syllable, Lancaster. Not like actor Burt Lan-cas-ter, who, as a Hollywood actor engaged in silly dress-up and fanciful make-believe his whole life, was the ultimate alien to our deal-in-real, natural, down-home, farming and mountain dweller environment here.

So say it again, quickly, Lancaster.

No time or spaces between what your head tells you are syllables. Say it again, fast, one quick word, Lancaster.

There, you said it, and we like you already. See? You fit right in, you hillbilly, you. Here’s a gun, and a Bible. Display them prominently in your home.

Bear and Deer Seasons in the Rearview Mirror

The old joke about Pennsylvania having just two seasons rings as true today as it did fifty years ago: Road construction season in the Keystone State seems to be a nine-month-long affair everywhere we go, a testament to how not to overbuild public infrastructure, if you cannot maintain it right.

And the two-week rifle deer season brings out the passion among nearly one million hunters like an early Christmas morning for little kids (I doubt the Hanukkah bush thing ever took off). All year long people plan their hunts with friends and relatives, take off from work, spend lots of money on gear, equipment, ammunition, food, and gas, and then go off to some place so they can report back their tales of cold and wet and woe to their warmer family members at home. These deer hunts are exciting adventures on the cheap. No bungee jumping, mountain cliff climbing, jumping through flaming hoops or parachuting out of airplanes are needed to generate the thrill of a lifetime as a deer or bear in range gives you a chance to be the best human you can be.

Both bear and deer seasons flew by too fast, and I wish I could do them over, not because I have regrets, but because these moments are so rare, and so meaningful. I love being in the wild, and the cold temperatures give me impetus to keep moving.

One reflection on these seasons is how the incredible acorn crop state-wide kept bear and deer from having to leave their mountain fortresses to find food. Normally animals must move quite a bit to find the browse and nuts they need to nourish their bodies. Well, not this year. Even yesterday I was tripping over super abundant acorns lying on every trail, human or animal made.

When acorns are still lying in the middle of a trail in December, where animals walk, then you know there are a lot of nuts, because normally those low-hanging fruits would be gobbled right up weeks ago.

After still hunting and driving off the mountain I hunt on most up north, it became clear the bear and deer were holed up in two very rugged, remote, laurel-choked difficult places to hunt. Any human approach is quickly heard, seen, or smelled, giving the critters their chance to simply walk away before the clumsy human arrives. All these animals had to do was get up a couple times a day, stretch, walk three feet and eat as many acorns as they want, and then return to their hidden beds.

This made killing them very difficult, and the lower bear and deer harvests show that. God help us if Sudden Oak Death blight hits Pennsylvania, because that will spell the end of the abundant game animals we enjoy, as well as the dominant oak forests they live in.

The second reflection is how we had no snow until Friday afternoon, two days ago, and by then we had already sidehilled on goat paths, and climbed steep mountains, as much as we were going to at that late point in the season. With snow, hunting is a totally different experience: The quarry stands out against the white back ground, making them easier to spot and kill, and snow tracking shows you where they were, where they were going, and when. These are big advantages to the hunter. Only on Friday afternoon did we see all the snowy tracks up top, leading over the steep edge into Truman Run. With another two hours, we could have done a small push and killed a couple deer. But not this year. Maybe in flintlock season!

And finally, I reflect on the people and the beautiful wild places we visited.

I already miss the time I spent with my son on stand the first week. He was with me when I took a small doe with a historic rifle that had not killed since October 1902, the last time its first owner hunted and a month before the gun was essentially put into storage until now.

And then my son had a terrible case of buck fever when a huge buck walked past him well within range of his Ruger .357 Magnum rifle, and he missed, fell down, and managed to somehow eject the clip and throw the second live round into the leaves while the deer kept moseying on by. When I found my son minutes later, he was sitting in a pile of leaves where the deer had stood, throwing the leaves around and crying in a rage that we needed to get right after the deer and hunt them down. The boy was a mess. It was delightful to watch.

I miss the wonderful men I hunted with, and I miss watching other parents take their own kids out, to pass on the ancient skill set as old as humankind.

It is an unfortunate necessity to point out that powerline contractor Haverfield ruined the Opening Day of deer season for about three dozen hunters by arriving unannounced and trespassing in force to access a powerline for annual maintenance in Dauphin County. We witnessed an unparalleled arrogance, dismissiveness, and incompetence by Haverfield staff and ownership that boggles the mind. I am a small business owner, and I’d be bankrupt in three days if I behaved like that. Only the intervention of a Pennsylvania Game Commission Wildlife Conservation Officer saved the day, and that was because the Haverfield fools were going onto adjoining State Game Lands, where they also had no business being during deer season.

Kudos to PPL staff for helping us resolve this so it never happens again.

Folks, we will see you in flintlock season, just around the corner. Now it is time to trap for the little ground predators that raid the nests of ducks, geese, grouse, turkey, woodcock, and migratory songbirds. If you hate trapping, then you hate cute little ducklings, because the super overabundant raccoons, possums, skunks, fox, and coyotes I pursue eat their eggs in the nests, and they eat the baby birds when they are most vulnerable.

The Bob Webber Trail takes on a whole new meaning

The Bob Webber Trail up between Cammal and Slate Run in the Pine Creek Valley is a well-known northcentral Pennsylvania destination. Along with the Golden Eagle Trail and other rugged, scenic hiking trails around there, you can see white and painted trilliums in the spring, waterfalls in June, and docile timber rattlers in July and August, as well as large brook trout stranded in ever-diminishing pools of crystal clear water as the summer moves along.

Bob Webber was a retired DCNR forester, who had spent the last 40 years or so of his life perched high above Slate Run in a rustic old CCC cabin. That is the life that many of the people around here aspire to, and which I, as a little kid, once stated matter of factly would be my own quiet existence when I reached the “big boy” age of 16. Except Bob had been married for almost all of his time there. He was no hermit, as he enjoyed people, especially people who wanted to explore nature off the beaten path.

That Bob had contributed so much to the conservation and intelligent development of Pine Creek’s recreational infrastructure is a well-earned understatement. He was a quiet leader on issues central to that remote yet popular tourist and hunting/fishing destination. The valley could easily have been dammed, like Kettle Creek was. Or it could easily have been over-developed to the point where the rustic charm that draws people there today would have been long gone. Bob was central to the valley’s successful model of both recreational destination and healthy ecosystem.

A year ago, while our clan was up at camp, Bob snowshoed down to Wolfe’s General Store, the source of just about everything in Slate Run, and I snapped a photo of my young son talking with both Bob and Tom Finkbiner, one of the other long-time stalwart conservationists in the valley. Whether my boy eventually understands or values this photo many years from now will depend upon his own interest in land and water conservation, nature, hunting, trapping, and fishing, and bringing urbanites into contact with these important pastimes so they better appreciate and value natural resources.

Bob, you will be missed. Right now you are walking the high mountains with your walking stick in your hand, enjoying God’s golden light and green fields on a good trail that never ends. God bless you.

Remembering neat people, Part 1

A lot of neat, interesting people have died in the past year or two, or ten, if I think about it, but time flies faster than we can catch it or even snatch special moments from it. People I either knew or admired from afar who changed me in some way.

There are two men who influenced me in small but substantial ways who I have been thinking about in recent days. One of them died exactly ten years ago, and the other died just last year. Funny how I keep thinking about them.

It is time to honor them as best I can, in words.

First one was Charlie Haffner, a grizzled mountain man from central Tennessee. Charlie and I first crossed paths in 1989, when I joined the Owl Hollow Shooting Club about 45 minutes south of Nashville, where I was a graduate student at the time.

Charlie owned that shooting club.

Back before GPS, internet, or cell phones, the world was a different place than today. Dinosaurs were probably wandering around among us then, mmm hmmmmm. Heck, maybe I am a dinosaur. Anyhow, in order to find my way to the Owl Hollow club, first and foremost I had to get the club’s phone number, which I obtained from a fly fishing shop on West End Avenue. Then I had to call Charlie for directions, using a l-a-n-d l-i-n-e, and actually speaking to a person at the other end. You’d think it was Morse Code by today’s standards.

After getting Charlie on the phone, and assiduously writing down his directions from our phone conversation, I had to use the best map I could get and then drive way out in the Tennessee countryside on gravel and dirt roads. Trusting my directional instincts, which are good, and trusting the maps, which were pretty bad, and using Charlie’s directions, which were exactingly precise, I made my way through an alien landscape of small tobacco farms and Confederate flags waving from flagpoles. Yes, southcentral Tennessee back then, and maybe even today, was still living in 1865. Not an American flag to be seen out there by itself. If one appeared, it was either directly above, or, more commonly, directly below the Confederate flag. The Confederate flag shared equal or nearly equal footing with the American flag throughout that region.

Needless to say, when I had finally arrived at the big, quiet, lonesome gun range in the middle of the Tennessee back country, the fact that I played the banjo and was as redneck as redneck gets back home didn’t mean a thing right then. Buddy, I was feelin’…. Yankee, like…well, like black people once probably felt entering into a room full of Caucasians. I felt all alone out there and downright uncomfortable. And to boot, I was looking for a mountain man with a deeeeep Southern drawl, so it was bound to get better. Right?

Sure enough, I saw Charlie’s historic square-cut log cabin up the hill, and I walked up to it. Problem was, it had a door on every outside wall, so that when I knocked on one, and heard voices inside, and then heard “Over here!” coming from outside, I’d walk around to the next door, which was closed, and I would knock again, and go through the process again, and again. Yes, I knocked on three or four of those mystery doors before Charlie Haffner finally stepped out of yet one more doorway, into the sunshine, and greeted me in the most friendly and welcoming manner.

Bib overalls were meant to be worn by men like Charlie, and Charlie was meant to wear bib overalls, and I think that’s all he had on. His long, white Father Time beard flowed down and across his chest, and his long, flowing white hair was thick and distinguished like a Southern gentleman’s hair would have to be. And sure as shootin’, a flintlock pistol was tucked into the top of those bib overalls. I am not normally a shy person, and I normally enjoy trying to get the first words in on any conversation, with some humor if I can think of it fast enough. But the truth is, I was dumbfounded and just stood there in awe of the sight before me.

Being a Damned Yankee, I half expected to be shot dead on sight. But what followed is a legendary story re-told many times in my own family, as Charlie (and his kindly wife, who also had a twinkle in her eye) welcomed me into his home in the most gracious, witty, and insightful way possible.

Over the following two years, I shot as much as a full-time graduate student could shoot out there at Owl Hollow Gun Club, which is to say not as much as I wanted and probably more than I should have. Although my first interest in guns as a kid had been black powder muzzleloaders, and I had received a percussion cap .45 caliber Philadelphia derringer as a gift when I was ten, I had not really spent much time around flintlocks. Charlie rekindled that flame in me there, and it has burned ever since, as it has for tens of thousands of other people who were similarly shaped by Charlie’s re-introduction of flintlock shooting matches back in the early 1970s, there at Owl Hollow Gun Club.

Charlie died ten years ago, on July 10th, I think, and I have thought about him often ever since: His incredible warmth and humor, his amazing insights for a mountain man with little evident exposure to the outside world (now don’t go getting prejudiced about mountain folk; he and many others are plenty worldly, even if they don’t APPEAR to be so), his tolerance of differences and willingness to break with orthodoxy to make someone feel most welcome. Hollywood has done a bad number on the Southern Man image, and maybe some of that negative stereotype is deserved, but Charlie Haffner was a true Southern gentleman in every way, and I was proud to know him, to be shaped by him.

The other man who has been on my mind is Russell Means, a Pine Ridge Sioux, award-winning actor, and Indian rights activist who caught my attention in the early 1970s, and most especially as a spokesman for tribal members holed up out there after shooting it out with FBI gunslingers.

American Indians always have a respected place in the heart of true Americans, and anyone who grew up playing cowboys and Indians knows that sometimes there were bad cowboys who got their due from some righteous red men. Among little kids fifty years ago, the Indians were always tough, and sometimes they were tougher and better than the white guys. From my generation, a lot of guys carry around a little bit of wahoo Indian inside our hearts; we’d still like to think we are part Indian; it would make us better, more real Americans…

Russell Means was a good looking man, very manly and tough, and he was outspoken about the unfair depredations his people had experienced. While Means was called a radical forty years ago, I think any proud Irishman or Scottish Highlander could easily relate to his complaints, if they or their descendants stop to think about how Britain had (and still does) dispossessed and displaced them.

Russell Means played a key role in an important movie, The Last of the Mohicans. His stoic, rugged demeanor wasn’t faked, and he was so authentic in appearance and action that he easily lent palpable credibility to that artistic portrayal of 1750s frontier America by simply showing up and being there on the set. Means could have easily been the guy on the original buffalo nickel; that is how authentic he was.

Russell Means was representative of an older, better way of life that is disappearing on the Indian reservations, if that makes any sense to those who think of the Indian lifestyle that passed away as involving horses and headdresses. He was truly one of the last of the Mohicans, for all the native tribes. Although I never met you, I still miss you, and your voice, Mr. Means.

[Written 7/23/14]