Posts Tagged → landowner

Please do not pet the landowner

A few weeks ago, my wife looked up, startled. Her eyes were fixated on something over my right shoulder, and then she said “There are some men on the porch. Were you expecting visitors today?”

Uh, no, I was not only not expecting any visitors that day, I was not expecting any visitors the entire weekend. Because I was alone with my wife and relishing our rare private time together in a quiet out of the way dead-end location.

Just as I stood up from the table and turned towards the front door, an older guy with a greying stubble knocked. Another guy in his fifties was standing near him, and both were dressed in casual-to-ratty-on-the-crick clothes. I did not recognize either of them, and reflexively felt for the grip of “Biden’s Lung Buster” at my side.

Opening the door and stepping outside, I buried my rumbling fury under a big steaming pile of humor: “Hi boys! You can put the free beer here on the porch and help yourselves to load of firewood on the way out.”

With big smile, of course.

The two men were nice enough, and laughed at my joke. They explained that they had been fishing down in the creek that morning and had heard a gobbler up above them on the mountain. And that had set them in motion trying to figure out a way to get to the gobbler, to hunt it, without trespassing on what they acknowledged is very clearly posted private land all around the gobbler.

After what they said was a lot of driving around and walking and consulting maps, they determined the best way to attain their goal was to drive up the posted and very long gravel driveway to the remote home nestled way the hell back in the woods, and then to knock on the door and ask permission to both hunt the gobbler at present time and in the future cross over our property to access state forest land farther up the mountain.

“You two bastards are lucky as hell I didn’t come busting out here buck naked with an AR to run you off, because the angry naked old man thing is about a hundred times worse than the gun,” I half joked.

The two interlopers chuckled at the joke, and started getting the hint. After all, the land AND the driveway are all posted for a reason. Privacy is a valuable and rare thing, and because many Americans today seem to have been raised without any manners or a sense of self-preservation, big yellow posted signs, buckets of purple paint, and gates are now a necessity to preserve what shreds of privacy people have remaining to them.

But these guys had purposefully ignored all of the legal and physical barriers designed to keep them out of my private life.

“Yeah, I have had that same bird in gun range twice this week, including earlier this morning, and I have decided to let him live, because he is a rare survivor up here,” I explained, truthfully.

Wild turkeys used to be plentiful in Northcentral PA, and for the past fifteen years they are now as rare as hen’s teeth, due to a combination of factors like mature forests and craploads of nest-raiding predators.

“Well, could we at least cross over your land to get to the state land?” the second guy asked, having taken a step backwards off the porch and onto the steps.

To which I replied with bare naked contempt: “Why would we let strangers walk through our best hunting ground so they can go hunt where they want? We leave that area as a sanctuary so we can hunt it carefully, and having people walk through it would just ruin it for our hunting, to say nothing of our privacy up here. And it is remote and quiet up here…right? Guys, there are over two million acres of public land within an hour’s drive of here, and you guys need to be here, right here, on us?”

The second guy looked chagrined, and I felt only the slightest twinge of regret for having spoken so plainly.

“Well, we thought it wouldn’t harm anything if we asked,” said the first guy, who was studying his feet.

And that’s the thing. The signs around the property and at the gate on the private driveway do not say “Hunting By Written Permission Only” or anything similar about asking for permission to hunt on the land.

Rather, the myriad signs and purple paint say keep out, stay out, do not enter, do not trespass, no access, no anything, private land don’t even ask. And frankly, every square inch of private land in the valley (which is about 93% public land) is heavily posted and jealously guarded, so physically asking anyone for permission to hunt is both a fool’s errand and a deliberate theft of someone’s valuable privacy. It is an invasion of someone’s sanctuary.

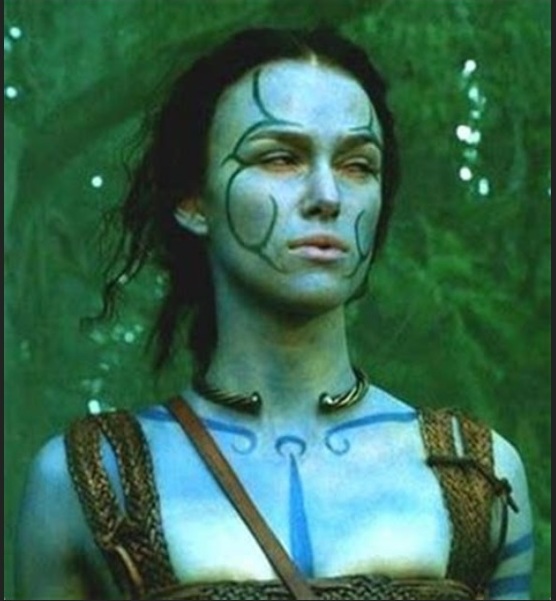

Folks, don’t try to pet the landowner. He is likely to bite, because he was sleeping comfortably in his quiet little corner when you came up to him, woke him up, and acted like petting him was the best thing he could have ever expected or wanted. When in fact all he wants is to be left alone in his quiet little corner. He never asked you to pet him and doesn’t want you to pet him. He doesn’t want to see or hear you, either.

For some odd reason, a lot of people across America believe that public land sucks to hunt on, and that private land is where all the wild game is holed up. Nothing is farther from the truth than this incorrect notion; almost all of the trophy deer and bears I have killed were on public land. If getting to a piece of public land is difficult, then you should do everything legal you can to get there, because in my extensive experience, hardly anyone else will be hunting that area. But one thing you cannot do is badger the adjoining private landowner. Sending a letter explaining yourself, or placing a friendly phone call, is the only correct way to ask permission.

PA’s must-do 21st century deer management policy

When Gern texted me on November 12th “planning to plant the entire farm with grass next Fall… 100% hay… can’t afford to feed wildlife. Going broke trying to make money,” I knew that my best deer management efforts had finally failed over the past 13 years.

Every year I work hard to make sure our deer season is as productive as possible. Because our tenant farmer pays us a per-acre rent every year, which covers the real estate taxes and some building maintenance, and for 13 years he has grown soybeans, corn and hay in various rotations across the many fields we have. Our arrangement has generally worked out well both ways, but that text message ended my sense of satisfaction.

While I do wear dirty bib overalls when I run the sawmill and also when I try to impress people who don’t know me, Gern is the actual farmer who tills (broad sense), fertilizes, plants, and harvests a very large farm property in Dauphin County, some of which I own and all of which I manage. Our property is one of many that comprise about 30,000 acres of farm land that Gern and his family cultivate in Central Pennsylvania. To say that his family works hard is the understatement of all understatements. Gern embodies AMERICA! in flesh and spirit, and to see him so utterly beaten down by mere deer is heartbreaking.

Over the years I knew that both overabundant deer and bears were taking a significant toll on our grain crops (Gern’s primary source of family income), and so I worked hard to recruit the kinds of good hunters who would help us annually whittle down the herds, so that the pressure was taken off of our crops. About five years ago I proudly photographed one of our late-summer soybean fields, at about four super healthy feet high, indicating a minimal amount of deer damage. When I passed the soybean field pictures around to other farmers and land managers, nothing but high praise returned. And so I patted myself on the back for our successful deer management, and congratulated our guest hunters, who were killing about 25-35 deer a year on our property. Our hunters were filling an impressive 50% to 65% of the roughly 54 DMAP deer management tags we hand out every year, as well as some of their buck tags and WMU 4C tags.

But, change is life’s biggest constant, and while I rested on my hunting laurels, deer hunting changed under my feet. The past few years have seen a lot of change in the hunting world. First and biggest change is that hunters in Pennsylvania and other states are aging out en masse, with fewer replacements following them. This means that a lot less pressure is being brought to bear on the deer herd. Which means a lot more deer are everywhere, which is not difficult to see if you drive anywhere in Pennsylvania in a vehicle. There are literally tons of dead deer along the side of every road and highway, everywhere in Pennsylvania. We should be measuring this at tons-of-deer-per-mile, not just the number of dead deer and damaged vehicles. Frankly this overabundant deer herd situation is out of control not just for the farmers who feed Americans, but for the people who want to safely drive their vehicles to the grocery store. Hunters are sorely needed to get this dangerous situation under control, and yet Pennsylvania’s deer management policies favor overabundant deer herds to keep older hunters less crabby.

So, because I am about to break out the spotlights and AK47 to finally manage our farm deer the way they need to be managed (and yes, PA farmers are allowed to wholesale slaughter deer in the crops) (and yes, I feel the same way about our favorite forested places in the Northern Tier), here below is the kind of deer management/ hunting policy Pennsylvania needs via the PGC, if we are going to get the out-of-control deer herd genie back into its bottle and stop hemorrhaging farmland on the altar of too many deer:

- Archery season is too long. At seven weeks long, the current archery season lets a lot of head-hunters stink up the woods, cull the very best trophy bucks, and pressure the deer enough to make them extra skittish and nocturnal before rifle season begins. Even though rifle season is our greatest deer management tool. The same can be said of bear season, which is the week before rifle season. So shorten archery season and lengthen rifle season, or make the opening week of deer season concurrent with bear season, like New York does.

- Rifle season must be longer, and why not a longer flintlock season, too? Is there something “extra special” about deer come the middle of January, that they are prematurely off limits to hunting? Most bucks begin to drop their antlers in early February. Have three weeks of rifle season and then five weeks of flintlock season until January 30th, every year. Or consider flintlock hunting year ’round, or a spring doe season in May.

- More doe tags are needed. There are too few doe tags to begin with, and most doe tags sell out and are never used. This is especially true in WMUs 5C and 5D, where despite enormous tag allocations, tags quickly become unavailable. That is because individual hunters can presently buy unlimited numbers of doe tags, for some reason having to do with the way deer were managed in the 1980s…c’mon, PGC, limit of two or three doe tags for each hunter in these high-density WMUs, and at least two doe tags in Big Woods WMUs like 2G and 4C.

- Despite good advancements in reducing the regulatory burden on deer hunters this past season, there are still too many rules and restrictions. For example, why can’t our muzzleloading guns have two barrels? Pedersoli makes the Kodiak, a fearsome double percussion rifle that would be just the ticket for reducing deer herds in high deer density WMUs where the PGC says they want more deer harvests. But presently it is not legal. Another example is the ridiculous interruptions in small game seasons as they overlap with bear and deer seasons. This bizarre on-again-off-again discontinuity of NOT hunting rabbits while others ARE hunting deer is an unnecessary holdover from the long-gone, rough-n-ready bad old poaching days of Pennsylvania wildlife management. PA is one of the very few states, if the only one at all, with these staggered small game and big game seasons. Bottom line is hunting is supposed to be fun, and burdening hunters with all kinds of minutiae is not only not fun, it is unnecessary. Other states with far more liberal political cultures have far fewer regulations than Pennsylvania, so come on PA, give fun a try.

- Artificial deer feeding with corn, alfalfa, oats etc on private land during all deer and bear seasons must end. Not only does this “I’m saving the poor starving deer” nonsense lead to spreading deadly diseases like CWD, it artificially draws deer onto sanctuary properties and away from nearby hunters. Or it is baiting, plain and simple. Feeding causes overabundant deer to avoid being hunted during hunting season, but then quickly spread out on the landscape where they eat everything out of house and home when hunting season ends. This year up north (Lycoming and Clinton counties) is a prime example. We had no acorns to speak of this Fall, and whatever fell was quickly eaten up by early November. As the weeks rolled on through hunting season, the deer began leaving their regular haunts and unnaturally herding up where artificial feed was being doled out. This removed them from being hunted, and creates a wildlife feeding arms race, where those who don’t feed wildlife run the risk of seeing none at all. So either completely outlaw artificial feeding or let everyone do it, including hunters, so they can compete with the non-hunters. And yes, people who buck hunt only, and who do not shoot does, and who put out corn and alfalfa etc. for deer during hunting season, are not really hunters. They are purposefully meddling in the hunts of other people by trying to keep them from shooting “my deer.”

- PGC must better communicate to its constituency that too many deer result in unproductive farms that then become housing developments. Because the landowner and farmer must make some money from the land, if farm land can’t grow corn, it will end up growing houses, which no real hunter wants. So real hunters want fewer deer, at numbers the land and farms can sustain.

Purple woad. Or why hunting leases

Leasing land to hunt on is a big thing these days, and there is no sign of the phenomenon decreasing. Most of it is about deer and turkey hunting.

Hunting leases have been popular for a long time in states with little public land, like Texas, but the practice is now spreading to remote areas like suburban farms around Philadelphia and Maryland. So high is the demand for quality hunting land, and for just finding a place to hunt without being bothered, and so limited is the resource becoming, that leasing is a natural step for many landowners who want to get some extra income to pay their rent or fief to the government (property taxes aka build-a-union-teacher’s-public-pension-fund).

Having been approached about leasing land I own and manage, it is something I considered and then rejected. If a landowner at all personally enjoys their own land themselves, enjoys their privacy there, enjoys the health of their land, then leasing is not for you. Bear in mind that leasing also carries some legal liability risk, and so you have to carry sufficient insurance to cover any lawsuits that might begin on your land.

Nonetheless, some private land is being leased, having been posted before that. And the reason that so many land owners are overcoming the same hurdles that I myself went through when considering land leasing, is that in some cases the money is high enough. Enough people want badly enough to have their own place that they can hunt on exclusively, that they are willing to pay real money.

Makes you wonder what kind of population pressures and open land decreases America has seen over the past fifty years to lead to this kind of change in land use. Makes me think of one anecdotal experience.

On the Sunday of Memorial Day Weekend of 2007, I drove up to Pine Creek to dig the footers for our barn. All the way up I shared the road, in both directions, with two motorcyclists headed in my same direction. That is it. In addition to my pickup, a grand total of two vehicles out for a Sunday drive in the country were on Route 44 and Rt 414.

Fast forward 13 years and my gosh, Pine Creek Valley has nonstop traffic in both directions at all hours. It does not matter what the time of day or night is, there are vehicles going in both directions. And not just oversize pickup trucks possibly associated with the gas drilling occurring around the area. Little tiny dinky tin can cars are going up and down the valley, too. There are literally people everywhere here now, in what had been the most remote, undeveloped, quietest corner of rural Pennsylvania. Even if you go bear hunting on some sidehill in the middle of nowhere up in Pine Creek Valley, you will encounter another hunting gang or two. Which for bear hunting is actually a good thing, but the point being that there are people everywhere everywhere everywhere in rural Pennsylvania.

OK, here is another brief anecdote. Ladies, skip ahead to the next paragraph. About ten years ago I was fishing on the north end of the Chesapeake Bay. When I was finished for the day, I drove back north toward home. At one point I had an urge to pee, so I began looking for a place I could pull off and pull out, without offending anyone. Yes, I have my modest moments. And you know what? The entire region between The Chesapeake Bay’s northern shores and the Pennsylvania Mason-Dixon Line, is completely developed. Like wall-to-wall one-two-three-acre residential lots on every inch of land surface. At the one place that finally looked like I was finally going to get some relief, I stepped out of the car and was immediately met with a parade of Mini Coopers and Priuses driving by on the gravel road to their wooded home lots. There was literally people everywhere, in every corner, in every place.

So what happened here?

There are more people and there is more land development, both of which leading to less nice land to hunt, fewer big private spaces for people to call their own, and so that which does exist is in much higher demand.

Enter Pennsylvania’s new No Trespassing law. AKA the “purple paint” law.

Why was this new law even needed? Because the disenfranchised, enslaved Scots-Irish refugees who originally settled the Pennsylvania frontier by dint of gumption, bravery, and hard work had a natural opposition to the notions and forms of European aristocracy that had driven them here. Such as large pieces of private land being closed off to hunting and fishing. And so these Scots-Irish settlers developed an Indian-like culture of openly flouting the marked boundaries of private properties. Especially when they hunted.

And this culture of ignoring No Trespassing signs carries forth to this very day.

Except that now it is 2020, not 1820, and there are more damned people on the landscape and a hell of a lot less land for those people to roam about on. Nice large pieces of truly private land are becoming something of a rarity in a lot of places. Heck, even the once-rural Poconos is now just an aluminum siding and brick suburb of Joizy.

So in response to our collision of frontier culture with ever more valuable privacy rights, Pennsylvania now has a new purple paint law. If you see purple paint on a tree, it is the equivalent of a No Trespassing sign. And if you do trespass and you get caught, the penalties are much tougher and more expensive than they were just a few months ago.

And you know what the real irony is of this purple paint stay-the-hell-out boundary thing? It is a lot like the blue woad that the Celtic ancestors of the Scots and Irish used to paint their bodies with before entering into battle. Except it is now the landowner who has painted himself in war paint.

Isn’t life funny.

Aggressive timber management necessary in the Northeast

When I tell some people how aggressively we try to manage standing timber (forests), they often recoil. It sounds so destructive, so environmentally wrong.

It is not environmentally damaging, but I will be the first to admit that the weeks and months after a logging operation often look like hell on the landscape: Tops everywhere, exposed dirt, skid trails, a tangled mess where an open woods had stood for the past sixty to eighty years just weeks before. No question, it is not the serene scene we all enjoyed beforehand.

This “clearcutting” gets a bad name from poor forestry practices out West and because of urban and suburban lawn aesthetics being misapplied to dynamic natural forests.

However, if we do not aggressively manage the forest, and the tree canopy above it, then we end up with tree species like black birch and red maple as the dominant trees in what should be, what otherwise would be a diverse and food-producing environment. Non-native and fire-sensitive species like ailanthus are quickly becoming a problem, as well.

When natural forest fires swept through our northeastern forests up until 100 years ago, these fire-sensitive species (black birch, red maple) were killed off, and nut trees like oaks, hickories, and chestnuts thrived. Animals like bears, deer, turkey, Allegheny woodrats, and every other critter under the sun survived on those nut crops every fall.

Without natural fire, which is obviously potentially destructive and scary, we must either set small prescribed fires, or aggressively remove the overhead tree canopy to get sufficient sunlight onto the forest floor to pop, open, and regenerate the next generation of native trees. Deer enjoy browsing young tree sprouts, so those tasty oaks, hickories, etc that lack sufficient sunlight to grow quickly usually become stunted shrubs, at best, due to constant deer nibbling. Sunlight is the key here.

And there is no way to get enough sunlight onto the forest floor and its natural seed bed without opening up the tree canopy above it. And that requires aggressive tree removal.

Northeastern forests typically have deep enough soils, sufficient rainfall, and gentle enough slopes to handle aggressive timber management. Where my disbelieving eyes have seen aggressive management go awry is out west, in the steep Rockies, where 1980s “regeneration cuts” on ancient forests had produced zero trees 25 years later. In fact, deep ravines had resulted from the flash-flooding that region is known for, and soil was being eroded into pristine waterways. So, aggressive timber management is not appropriate for all regions, all topography, or all soils.

But here in the northeast, we go out of our way to leave a huge mess behind after we log. Why? Because how things appear on their surface has nothing to do with how they perform natural functions. Those tangled tree tops provide cover for the next generation of trees and wildflowers, turtles and snakes, and help prevent soil erosion by blocking water and making it move slowly across the landscape.

Indeed, a correctly managed northeastern forest is no place for urban or suburban landscape aesthetics, which often dictate bad “select cut” methods that work against the long term health and diversity of the forest, as well as against the tax-paying landowner.

So the next time you see a forest coming down, cheer on the landowner, because they are receiving needed money to pay for the land. Cheer on the loggers and the timber buyers, the mills and manufacturing plants, and the retailers of furniture, flooring, and kitchen cabinets, because they all are part of a great chain of necessary economic activity that at its core is sustainable, renewable, natural, and quintessentially good.

A win for the little guy

Government’s role is to serve the people. America is a people with a government, not a government with a people. The people – their needs, their interests, their rights – come first in all things. Our Constitution prohibits government behavior that is arbitrary, capricious, abusive, or uncompensated taking of private property, among others.

Any American who loses sight of these limitations has fallen into the easy trap of promoting government over the people. People in both main political parties fall into this trap, because both main parties have largely lost touch with the US Constitution (and the Pennsylvania Constitution) and its daily meaning for American citizens.

Last night the Pennsylvania state senate passed HB 1565, which amended through law a procedural environmental rule issued in the last days of the former Governor Ed Rendell administration, in 2010. The rule created 150-foot buffers along streams designated High Quality and Exceptional Value, and removed that buffer land from nearly all uses. No compensation to the landowner was provided. Allowing the landowner to claim a charitable donation for public benefit was not allowed. Higher building density on the balance of the property was not allowed. The buffer land was simply taken by government fiat, by administrative dictate, totally at odds with the way American government is supposed to work.

And the appeal process afforded to landowners under the rule was onerous, extremely expensive, and lengthy. It was not real due process, but rather a series of high hurdles designed to chase away landowners from their property rights. Everything about this rule was designed to make the government’s job as easy as possible, and the private property owner’s rights and abilities as watered down as possible.

The 150-foot buffer rule represented the worst sort of government, because it did not serve the people, it quite simply took from the people. The 150-foot buffer rule was blunt force trauma in the name of environmental quality, which can easily be achieved to the same level myriad other ways. The rule was the easy way out, and it represented a throwback to the old days of the environmental movement and environmental quality management when big government, top-down, command-and-control dictates were standard fare for arresting environmental degradation.

That approach made sense when polluted American rivers were catching fire, nearly fifty years ago. Today, a scalpel and set of screwdrivers can achieve the environmental goal much better, and fairly. Supporters of the rule claimed that voting for HB 1565 was voting against environmental quality, which made no sense. Environmental quality along HQ and EV stream corridors could have easily been achieved with a similar, but innately fairer, 150-foot buffer rule. It saddens me that my fellow Americans could not see that simple fact, and instead sought to stay with a deeply flawed government process until the bitter end.

I know the people who both created and then championed the rule. Some of them are friends and acquaintances of mine. Their motives and intentions were good. I won’t say that they are bad people. Yes, they are mostly Democrats, but there were also plenty of Republicans involved in designing it and defending it, including former high level Republican government appointees.

Rather, this rule was a prime example of how simply out of touch many government decision makers have become with what American government is supposed to be, and it adds fuel to my own quest to help reintroduce the US and Pennsylvania constitutions back into policy discussions and government decision making so that we don’t have more HB 1565 moments in the future.