Posts Tagged → book

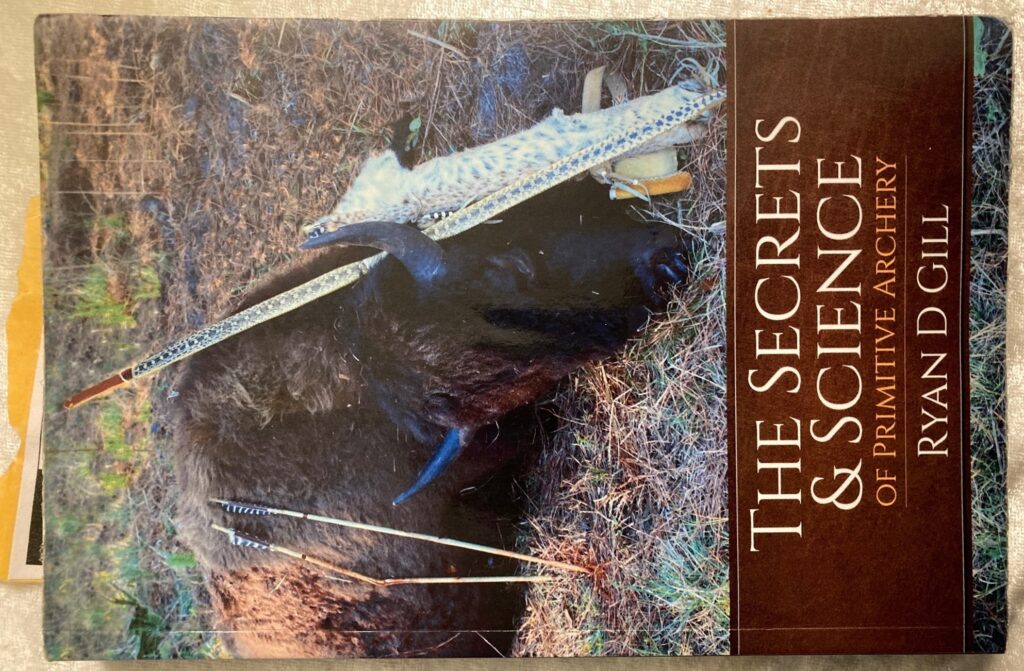

Book review: Secrets & Science of Primitive Archery

Ryan Gill’s book, The Secrets & Science of Primitive Archery, is a must-have for all stick bow hunters. You cannot find your way in the dark without a light, and this book is the illumination every traditional and self-bow hunter needs. I don’t care how long you have been hunting with your Osage orange self-bow or even a traditional bow by a small maker. If you hunt with something that does not have training wheels, then you need this book.

I must admit that I am almost ashamed it has taken me over a YEAR to review this book. Actually almost two years. Author Ryan Gill deserves much better treatment for all the hard work he put into this book. What can I say, Ryan. America has had a lot of ups and downs since 2021, and for political watchers and commenters like me, practically every day has felt like an all-hands-on-deck. All the political stuff has taken up the blog space. I am sorry, buddy. Hopefully I finally give you and the excellent book your due here.

As a traditional archery hunter since I was about fourteen, I have been enamored of bows made of a simple stick and a string. When us kids made our own bows out of saplings we cut in our woods (fifty years ago…), we would tie on a piece of baling twine and shoot arrows made of tree branches, goldenrod, whatever we could get our hands on, and practice with what we had. As the years went past, some of us were gifted compound bows, and others got simple recurves. I got a recurve, and some pretty sorry secondhand Easton aluminum arrows, to which I attached basic Bear broadheads.

If I had a nickel for every deer I collected hair from, I would have enough to buy a malted milkshake at the Lewisburg Freeze, which was fifty cents way back when, and costs five bucks now. That is to say, I never killed a deer with a bow, but missing didn’t stop me from trying.

Fast forward and I had my own kids, all of whom enjoyed shooting little fiberglass kid bows. When the boy attained the age of about seven, he demanded a “real bow,” and so off to the Eastern Traditional Archery Rendezvous we went. There we located a nice faux curly maple kid recurve with about 20 pounds of pull. Enough to skewer a squirrel or ball up a bunny in the back yard, which the boy kept after. Many years later we would go back to ETAR to get his real Big Boy bow, a reflex-deflex by the Kilted Bowyer. At 43 pounds pull weight at 26 inches, this is a true hunting machine, pretty, yes, but in all the clean simplicity a true bow should have.

But in between the little boy bows and the last big boy bow there were a lot of experiments over the years. Saplings cut, strings attached, arrows made, trials run. Like I did when I was a kid fascinated with the basic but powerful physics of archery. And this is where Ryan Gill’s fascinating book enters the picture.

Ryan Gill came to our attention by his YouTube videos. Because we were naturally looking for information about what we were doing right and doing wrong. Ryan doesn’t just cut saplings, attach a string, and shoot some crappy home made arrows. Au contraire! Ryan makes all kinds of powerful self-bows from all kinds of different woods, including Osage orange, hickory, black locust, and others, that will kill deer, bear, wild hogs, and even huge bison. And then Ryan strings the bows with real animal gut. And then he makes real cane arrows, tipped with real flint and chert heads that he himself knapped. Talking the real deal here. And through it all in his videos and his book, Ryan explains how primitive archery really worked tens of thousands of years ago, and how it can work really well for us today.

I learned a lot from this book.

Because I am a numbers guy, Ryan’s statistical analysis of his different bows, using different strings (animal and plant fiber), using different arrow shafts (river cane, wood) etc, really speaks to me. He does a great job of tabulating his data, which, when all his testing is said and done, tells us exactly where to go: Osage orange bow stave that is dried daily, using either a modern bow string or an animal gut string, and shooting properly made river cane shafts fletched with goose feathers and tipped with the proper and surprisingly small stone arrowhead, that go at least 130 feet per second, with 150 fps or better being the best and most likely to catch an unaware deer standing flat-footed.

If you are at all a traditional or aspiring primitive archery person, you need this book. This is a must-have resource that you will find nowhere else. It has an incredible amount of fascinating and directly applicable how-to information to every step and facet of primitive and traditional archery, as well as the historic and anthropological background to how primitive archery evolved. I read it twice before I felt qualified to write about it here, and I highly recommend it.

Book review: A Rebel from the Start by Avi Yemini

Like a lot of news hounds disgusted by the brazenly partisan establishment narrative activists at the “mainstream media” outlets like MSNBC, CBS, NBC, ABC, NPR, PBS, Reuters, the Associated Press, the New York Times, the Washington Post et al ad nauseum, I have spent years chasing down the few actual news sources that would give me the facts and just the facts. Sites like The Gateway Pundit, Breitbart, Zero Hedge, the Epoch Times, and podcasts by Dinesh D’Souza, Dan Bongino, and Jan Jekeliek now give me a 360 degree news and information coverage that has been sorely lacking for so long.

One of my most recent finds was Rebel News, back in 2020, when the world was melting down about Covid and hardly any news outlets were asking any questions about why the world was melting down about Covid.

I was up in the mountains, usually alone, running the sawmill and physically exposed to no one, with my main link to the outside world the very slow internet connection we had then. Then as now, the establishment media simply carried the establishment narrative and fear-mongering political message for the blatantly corrupted CDC and other federal agencies so visibly taken over by the pharmaceuticals industry. Rebel News was different, and from 2020 into 2021 its founder, Ezra Levant, really stood out by asking basic questions. He asked questions of people in power, he asked questions of people in official positions, he asked questions of police officers gleefully and violently enforcing Covid lockdowns in Canada and Australia, and he asked questions of people in the street. How refreshing! A real newsman!

Rebel News then added a few truly intrepid reporters like David Menzies, Sheila Gunn, and a confusing man named Avi Yemini. I don’t want to make this book review all about Rebel News and Ezra Levant, but the fact is that without Rebel News, the free world (ha) would know a lot, lot less about Covid tyranny than we know now. And what we know now has informed freedom loving citizens across Canada, America, Australia, and Europe to demand an end to health tyranny and a return to responsive, representative government.

While all of the Rebel News reporters have done really amazing work, one of them stood out, this earnest, tattooed, sometimes almost innocently child-like Avi Yemini fellow. He was unafraid and would wade right into the lockdown protests with his Rebel News microphone, and was often dogged by Jew haters and violent government thugs alike.

Sheila Gunn, Ezra Levant, David Menzies and other Rebel News reporters all have done great work, but none of them have the cool Australian accent, the Jewfro, or the odd name that Avi Yemini has. And so I really began to closely follow every video and interview he put out. Because Avi Yemini has a foot in about a half dozen different worlds simultaneously, I was more than intrigued. Who was this guy? Why did he remind me of the ADD prancing black knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail? Where the hell did he come from? Why was he so laid-back-open-minded on the one hand, and yet asking such pointed questions of people in power on the other hand?

His interviews along with Ezra Levant of Hitler Youth climate grifter Greta Thunberg and ultra shady Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla put Rebel News squarely in the international spotlight. He then had an amazing followup debate with Nas Daily, an Israeli Arab who is so fully integrated into the establishment that he carries all the water left in the Middle East for all the political establishment there.

Just when I thought I could not take the suspense any longer, Avi Yemini wrote a book about himself, which debuted a few months ago. Titled “A Rebel from the Start,” Avi seems to bare all in this book. I mean, I don’t think he leaves much to the imagination. Said another way, he seems to be much more honest about his childhood and his failures than anyone else I know would be. Reading the book helped me understand Avi personally, but not really politically, or ideologically. And I am unsure if that understanding will ever happen for me, anyone else, or even for Avi himself. To wit, he is from an Orthodox Jewish family, married to a woman of unclear religious beliefs but who has two Muslim kids from her first marriage. Add in Avi’s two kids and you get this big, boisterous mini riot blur of activity, full-on life engagement, and earnest questions about everything, and yet rigid ideology about nothing.

Avi Yemini is the anti-ideology news reporter. He has no ideological axe to grind. This is so rare in the news business that it is tough to get my head around.

And I think this last observation is probably the most refreshing aspect of Rebel News’ reporting: They don’t do what the establishment media does, which is daily parrot a set of talking points meant to artificially buoy up the corrupt political establishment. Rather, Rebel News staff are unafraid to ask the glaring, most obvious questions that anyone with a scintilla of care about where Western Civilization is headed (presently down the tubes and gaining speed) would be interested in. Avi Yemini is a colorful, inquisitive, fearless, insightful interlocutor and news reporter, and his book is a fascinating read for those of us who have watched his rise in prominence with awe and wonderment. I highly recommend it.

You can buy Rebel from the Start here.

Actual news reporter Avi Yemini was constantly harassed and arrested by the Australian police (who later lost all their cases against him in court), while the fake news establishment political activist in drag as a “news reporter” is carefully protected by the Australian police. Avi is a freedom hero.

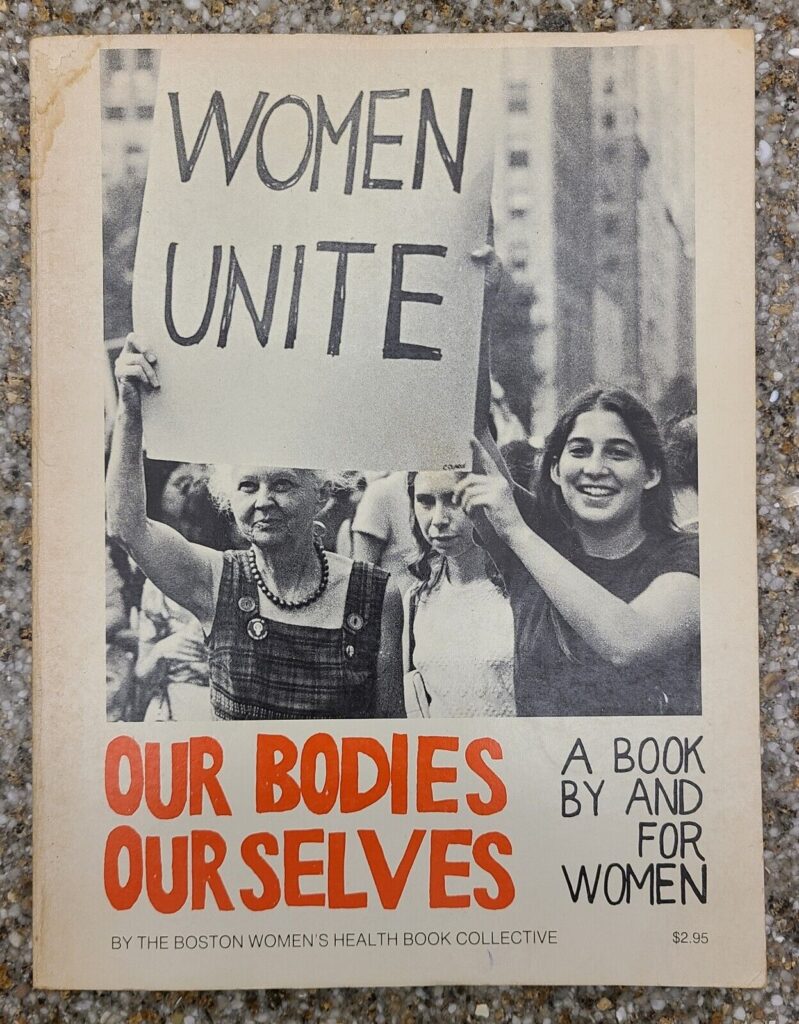

My body, my….self…?

My sense is that abortion was the issue of this week’s mid-term election. After all, all of the digital online advertising I received about Fetterman, Shapiro, and Mastriano was about that one issue. And Democrat Party poll workers confirmed their own belief that abortion would galvanize their voters. It seems to have worked, and fended off what was touted as a “red wave” of conservative response to failed governance in Washington DC.

My mind wanders back to 1972 or 1973, when I was a young kid, but old enough to become self aware. My hippie parents had the Our Bodies, Our Selves book laying out in the living room. When no adults were around I would look at this book and marvel at the array of hairy women parading their naked bodies in it. At an early age, then, I determined that naked woman was good, hairy was not good. One idea that sticks in my mind (having long ago eradicated the book’s “natural” images from my memory banks) is the novel concept that a person’s body is their own.

I think freedom-loving Americans can emphatically agree on this, that a person’s body is their own and nobody else’s. Where Americans diverge from one another is what is our body? Is it just the living, walking adult body, or does that also include young humans growing inside of it?

Reasonable people can and should debate this subject, and if pro-Life advocates want to make headway politically and culturally, then they have got to do a much better job explaining their perspective on when human life begins, why it is sacred, and how abortion-on-demand is not a my body, my self policy issue, but rather an “our bodies intertwined together” humanity issue. They must do a much better job, as this week’s election results demonstrate (assuming no election fraud occurred, which in some states is once again already obvious and in-your-face to the point of training voters to regularly accept it from one political party).

To be fair to the pro-Life anti-abortion voters, advocates, and candidates like Doug Mastriano, a lot of Americans felt like the two-year Covid1984 plandemic was one gigantic official assault on the idea of Our Bodies, Our Selves. A lot of voters this week showed up to vote against the unconstitutional government overreach, official lies, official illegalities, and government personnel self-enrichment that characterized the past two years of Covid1984. They thought other Americans felt the same.

Draconian lockdowns to the point of absurdity (lone sea kayakers being surrounded by heavily armed police boats and arrested for violating a “public health code,” sunbathers sitting totally alone on a beach, and married couples sitting alone in their car at scenic overlooks being similarly mistreated by aggressive police officers etc.), pointless and highly damaging school closures, useless mask requirements, and dangerous fake vaccine requirements that are now yielding an enormous number of vaccine-caused injuries and deaths, all and every aspect of the Covid1984 experience was one huge pile of Our Bodies, Our Selves books being symbolically burned by government staffers and leftist political activists in a joyous ceremony to mark the end of the idea that your body is yours and yours alone, and to emphasize that the government, their government, can do to you whatever it wants whenever it wants.

Conservative voters and candidates mistakenly thought that leftists would be consistent in their body sovereignty thinking, that everyone else felt the same (logically consistent) as conservatives about this disaster, and that they would vote accordingly.

And this is the confusing part of this my body, my self as a public policy issue and debate subject. On the one hand we have a lot of Americans who were and still are being severely damaged by the government’s purposefully bad handling of Covid1984, and they are pushing back. (Despite the Biden DOJ’s designation of them as “domestic terrorists” for merely speaking out in official taxpayer-funded venues.)

And on the other hand we have a lot of Americans who think that not only is the government’s brutal and useless Covid1984 overreach into your body and your body choices great public policy, but that the use of crushing government coercive force to implement it and force you to comply or be destroyed was just great, too. And yet a lot of these same people are the pro abortion Our Bodies, Our Selves believers who were animated enough to show up to vote this week.

This is confusing because it is inconsistent. Choice should be choice…right?

If you spend time reading this blog, then you already know I am not enamored of liberal/ leftist thinking, because I cannot make it make sense. And to be fair, most leftists and liberals I speak with about this are quite honest about it: They don’t care about logic, reason, or being consistent. They want their political issues the way they want them, and to hell with your criticisms.

In a democratic nation and in a Western Civilization based on logic, reason, debate, and persuasion, we have a conundrum here. Americans are talking right past each other, and not just about our bodies being sovereign from outside forces. Americans are failing to communicate with each other on a whole array of political and cultural topics. I am firmly on the side of reason, logic, and reasoned debate being at the center of our governance process, and so I stand firmly with the dreaded “conservatives.”

But I will say this to the conservatives, like governor candidate Doug Mastriano: If you are going to make the elimination or regulation of abortion your main public policy goal, then you had damned well better explain it to the public very carefully, frame it in context of the 2020-2022 Covid1984 government assault on Americans’ bodies, and you had better not do any interviews where snippets of your public statements can be used to paint you into a corner. At least half of America is not able or willing to discuss this subject, and to them only the axe-murdering abortion of a helpless and sacred child is their singular and joyous right; what the government does to their bodies the other 99% of the time is the business of the government and none of their own. They are not thinking clearly about this, and candidates must work hard to connect the abortion dot to the Covid1984 dot for future voters. Or don’t work on it, and shut the hell up about it.

And I will also say this to the liberals/ leftists: Your apparent worshiping of abortion as an act, to the point of killing the living, viable child at birth, makes you look like a primitive bloodthirsty death cult. This is not civilized behavior by people who advocate for myriad other intrusive government policies “if it saves just one child.” So long as you inhabit this childish shadowland of disconnected and strongly contrasting public policies, your fellow Americans will understandably deride you as foolish children who actually hate children.

Does this book also apply to the victims of bad government policies on Covid? If not, then there is no body sovereignty for anyone

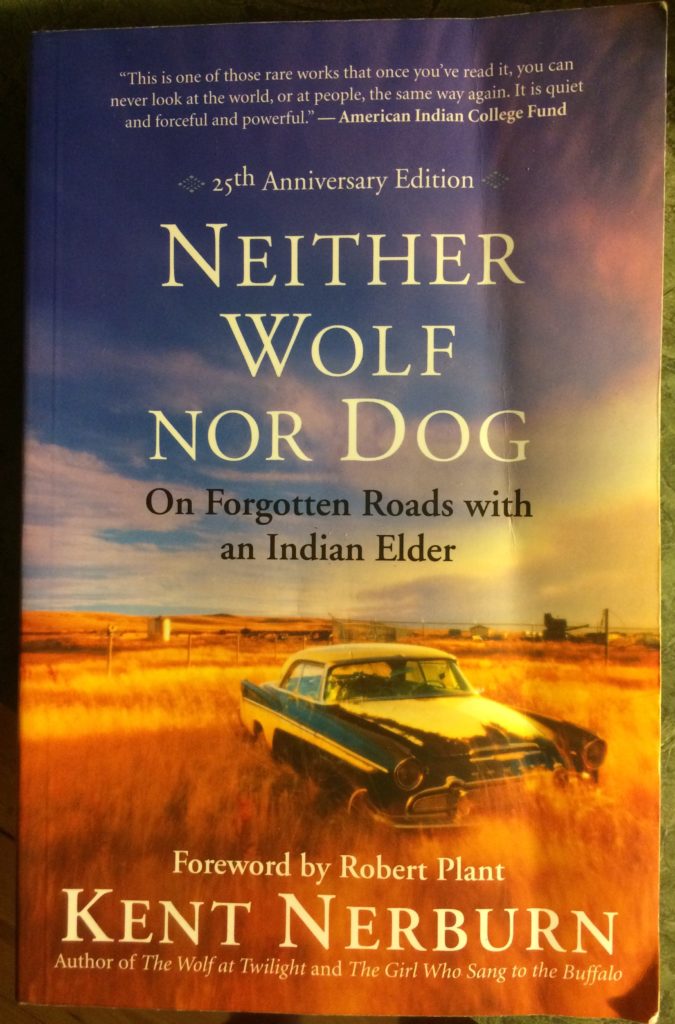

Book Review: Neither Wolf nor Dog

Given the recent road blocks by fake Indians (No, not presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren, but other white fake Indians inspired by her) in Canada, we have here a timely opportunity to look at a book about American Indians and the Caucasian people who purport to love them.

This is a Book Review of Neither Wolf nor Dog, about 1990s life on the rez, something I know a fair amount about, having seen it myself.

Kent Nerburn’s Neither Wolf nor Dog was kindly given to me as a gift by someone who knows I have a strong interest in American Indian history and welfare. And so I dutifully plowed through all 343 pages of this 1994 publication (reprinted in 2007 and 2017), a mysterious road trip set in the Dakotas. By the end of this book I felt like I, too, had been on a long, slow, arduous, winding trip. In fact, I felt sick from sitting in the back of the car.

This book does have some artistic merit. For example, the description of the lone Indian’s hands as “axe heads” at the end of his long, slender arms, actually conjures up some interesting images that ring true with some rural lifestyle body types. Here and there some creative writing exemplifies a writer trying to achieve more than racist propaganda.

At first I was intrigued by Nerburn’s first-hand narrative writing method. It sounds real enough, like this book is not fiction. But as he repeatedly decried other writers who falsely ascribe great mystical powers and innate supernatural wisdom to American Indians, Nerburn himself writes a book that is devoted to repeatedly ascribing great mystical powers and innate supernatural wisdom to American Indians. While openly mocking the contemporaneous movie Dances with Wolves for its many alleged trespasses against Indian history and culture, especially with Kevin Costner as the white liberal savior, Nerburn takes 343 pages to solidly present himself as the white liberal savior of the Lakota Sioux and of all other American Indian history, culture, and interests. A kind of keeper of the fire, he thinks. It is open hypocrisy, but for a meritorious purpose. Because his intentions are good…..

This method did not bother me at first, because I was certain that a writer so clearly violating his own red lines in the sand would surely have enough self awareness to not do it so blatantly himself. But as the pages plodded on and on, and the ‘Wise Sage Old One’, Dan, drones on and on in a preachy and accusatory voice, and with way more words than I have ever heard any Indian speak, I realized Nerburn was as one-dimensional as he appeared to be. Nerburn has just put his very white liberal guy words in the mouth of Dan the Lakota. And no un-truer words were ever spoken.

The writing problems here stem from Nerburn’s commitment to the publicly failed notion of “white guilt” and multiculturalism, that idea that everything Western and European is automatically bad, and that everything else is automatically good and legitimate, even cannibalism and violent criminal behavior.

To wit: ‘ “Forgive me.” The words passed from me like stones – hard, evil little balls of an illness that had stricken my soul, suddenly flung free, releasing me from years of torment. That was why I was here — not to help, but to earn forgiveness, to earn forgiveness for the shame in my blood.

“Forgive me,” I said again, confessing to unknown sins and transgressions , to my desire to leave, to my sense of righteousness and superiority, too my whiteness.’ (Page 135)

Multiculturalism celebrates the differences among Americans, instead of what unites them, while simultaneously trying to eradicate any sense of American-ness and painting as evil anyone here with “white” skin.

“...the shame in my blood…”? Who else carries a blood-guilt over generations that cannot be eradicated, hmmm? It’s nonsense.

Anyone trying to do something similar in say Poland, Russia, China, Zimbabwe, or Bolivia would be laughed out of polite company by the natives, who are quite proud of their own nations and histories. Only in a society as open and welcoming as America has the enticement to virtue signal at the expense of the nation been pursued and realized by people like Kent Nerburn.

For multiculturalists like Nerburn, history begins in 1509, when Europeans migrated to the New World. Neither Wolf nor Dog has history beginning in about 1889, and before that, it seems, the American West was a pastoral Eden full of peaceable Indians sitting around smoking sacred tobacco, beating drums, and occasionally having deep spiritual chats with bison before killing and eating them.

More nonsense. Indian violence, genocide, migration are ignored.

To multiculturalists, the human migration from Europe is a very bad thing, because it upset the inhabitants who had simply migrated there beforehand. Not to belittle the many crimes and grand thefts committed by the Conquistadores, the Portuguese, the Italians, the Catholic missionaries, or the US government in Washington, DC. But let’s be honest, the American Indians from the farthest reaches of the Arctic Circle to lowest temperatures around Tierra del Fuego did precisely and exactly the same violent things to each other, for far longer than the Europeans did them. And they did it without any remorse.

For example, the Cheyenne (Tsi Tsi Tas) took no adult male prisoners. Wounded enemies were summarily killed by Cheyenne warriors on the battlefield. Other Western tribes were much less merciful, and like almost all of the Eastern tribes, they made a great happy spectacle of slowly and sadistically torturing their captives to death.

The Aztecs and Mayans committed great acts of mass human butchery, to satisfy their gods’ bloodlust. Using captured slaves to build their cities and religious monuments, the great South American Indian cultures all raided, enslaved, massacred, and sacrificed one another for a long time. The Indians of North America also massacred, raided, murdered, and tortured one another for a very long time. That is, after they had all invaded, I mean migrated to the New World from Asia.

But to multiculturalists like Nerburn, none of this matters; because of “white guilt,” time and history artificially and inexplicably begin only when Europeans arrive in the New World. And so Neither Wolf nor Dog deals not in actual history, but in massive quantities of silly feelings over a very short amount of time. Sadness, shame, remorse, anger, and so on, all of it aimed at “white” people. It turns out that “white” people are greatly guilty. All of them, regardless of where or when they were born, lived, or did for a living.

If there is one theme that just repeatedly bangs the reader over the head in this book, it is that “we” “us” and “you” “white” people carry some great burden of sin, a terrible guilt, which can never be cleansed. Even if one is an Irish, Italian or Jewish American who arrived at Ellis Island by steamer in 1898 or 1910, without a buffalo nickel or Indian Head Cent in their pocket; or the descendant of one or all of these ethnicities. Pushing collective guilt of all “white” people is the primary purpose of this book. Even if your “white” skin carries the olive hues of the Mediterranean, or the pasty white of Europe’s lowest and most mistreated ethnic group, the Irish.

So in the name of being against racism, white guilt is a trans-generational racial culpability, not an individual crime committed on the Plains in 1876. It is the flip side of the white supremacist coin, and just as nonsensical.

What is wrong about this book is that it is possible for Americans to strongly support Indian treaty and land claims, and to relate to their bad feelings, without buying into the whole white liberal shame and guilt nonsense.

In real life, an animal that is neither wolf nor dog is a coyote. All of the Plains Indians regarded the coyote as the embodiment of crafty, sneaky dishonesty.

Cheyenne warrior George Bent relates first-hand one of General George Custer’s last personal encounters with Indians before he got his just desserts in a very real and up-close-and-personal encounter in 1876, was when he sought to entrap a number of Cheyenne to use as hostages in his negotiations to push the tribe onto various reservations.

Custer had invited the Cheyennes to meet and talk, supposedly, and as his troopers clumsily sprang their trap, most of the assembled Cheyenne jumped on their horses and fled. A few remained, foolishly trusting Custer to be a man of his word (they were all murdered in cold blood), but one brave rode his horse right up to Custer and waved his quirt in Custer’s face.

“You are nothing but a coyote,” said the young brave to Custer’s face, before galloping off to safety.

And I would say the same thing to Kent Nerburn: You are neither wolf nor dog, Nerburn. You are neither a strong, noble predator, the wolf, nor a useful, loyal friend, the dog. You are a coyote, Nerburn, like Custer and the government in Washington, DC. You have reduced these great Indian warriors to perpetual victim status, pathetically beating their symbolic drums and walking around with their heads down. Just like white liberals did to American Blacks – perpetual slaves, and victims, can’t help themselves, who must always be rescued by white liberals.

Talk about doing a disservice!

So there, I read this book for you. So you don’t have to.

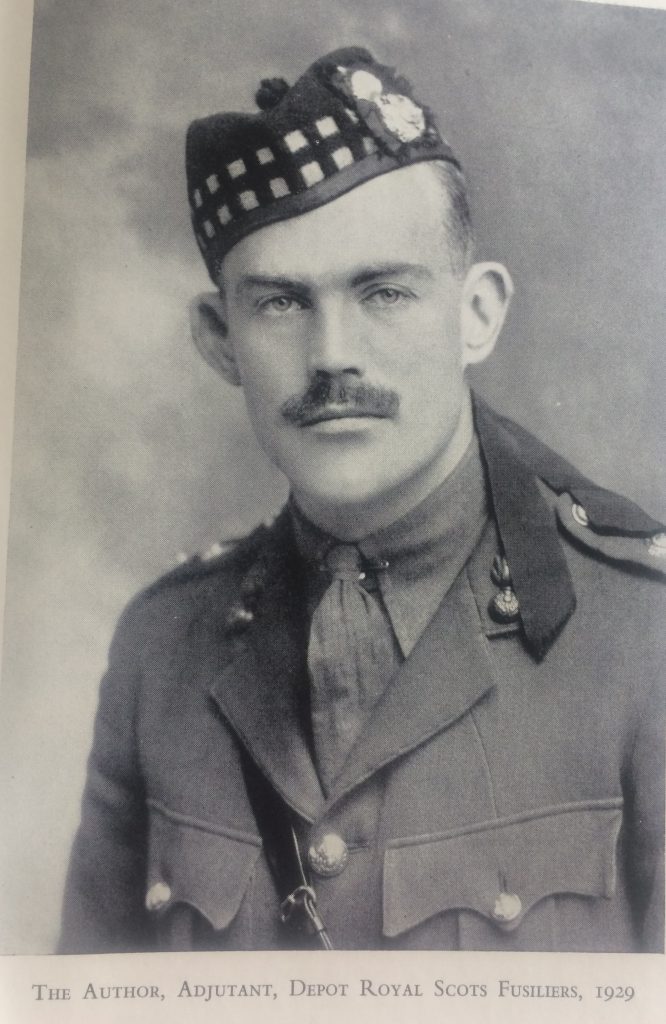

Book Review: The Uneven Road, by Lord Belhaven

The Uneven Road (1955), by Lord Belhaven

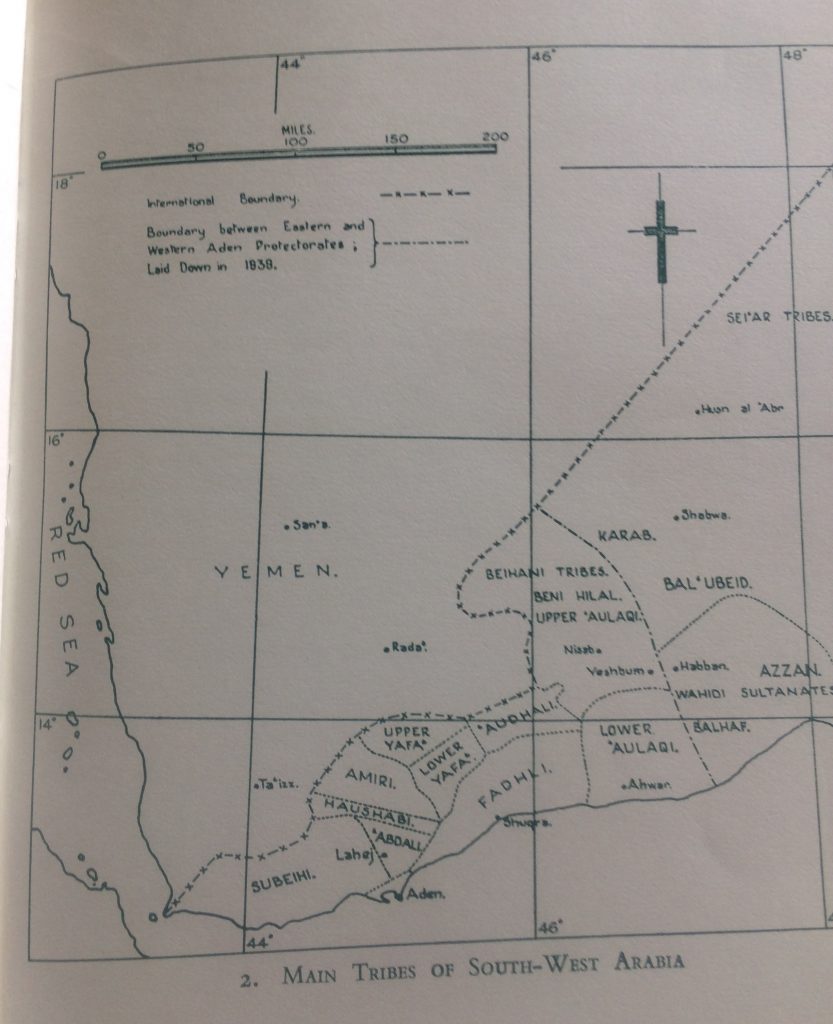

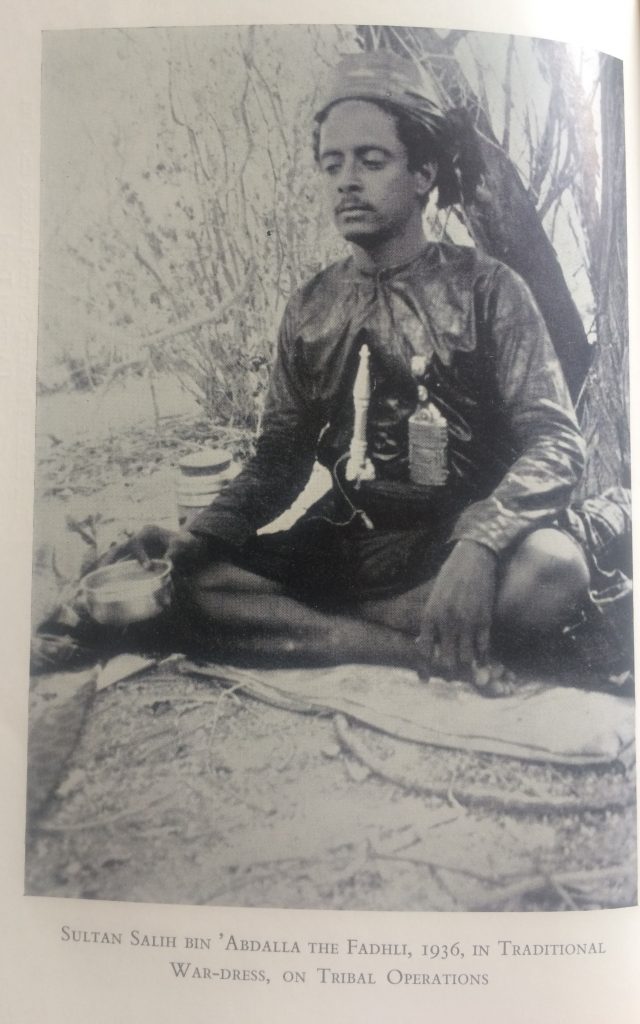

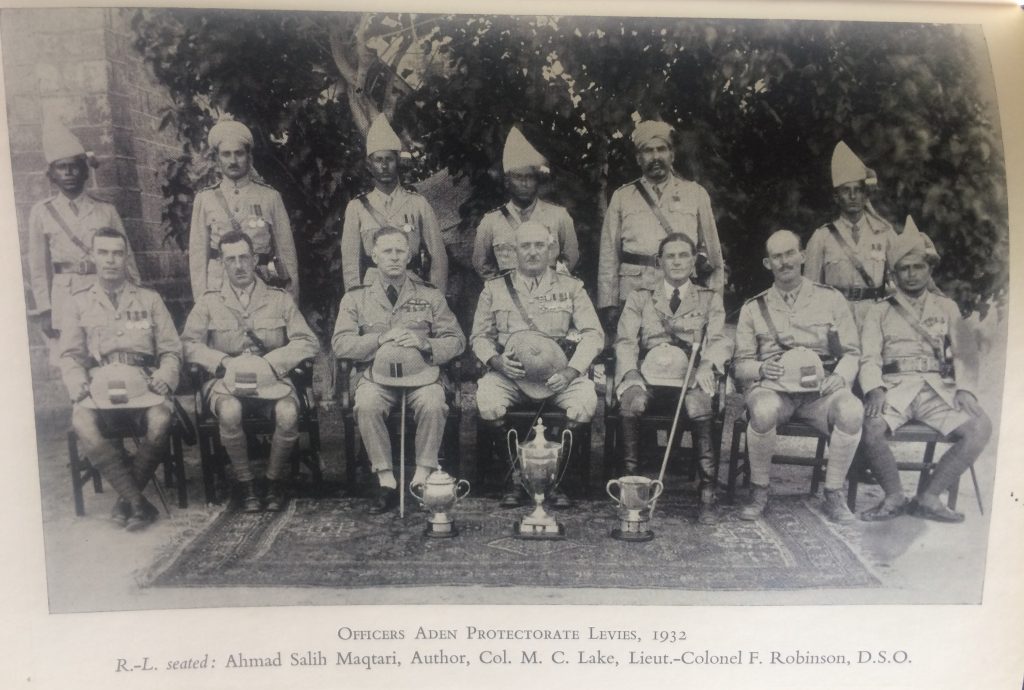

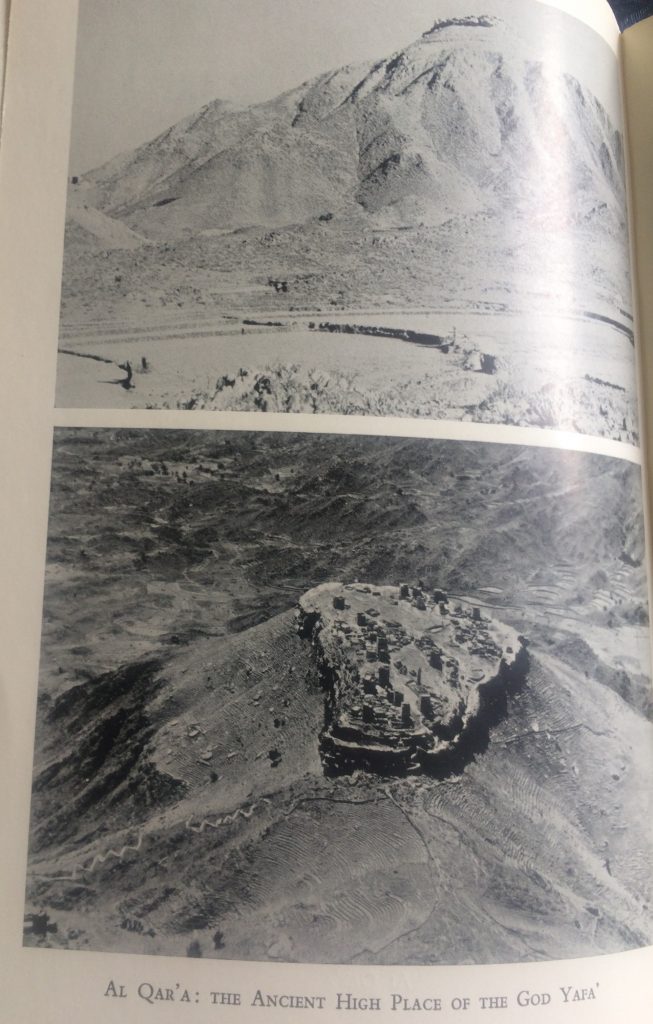

I read this fascinating book twice, and I recommend you read it at least once. Heck, just the old black and white photos of mysterious holy cities, like al Q’ara, (taken with early hand-held cameras from a bi-plane in the 1920s and 1930s) and traditional Arab tribesmen, both even today far out of reach of Westerners, are worth the five or ten bucks it’ll cost you to buy it on eBay or Amazon. For just five bucks you can get one of these fascinating and educational books, and have a most enjoyable weekend reading, and learning. Find me another great, safe, healthy mind trip for five bucks, please.

Why review a book published in 1955, about the now dead Brutish Empire? What made the British Empire so grand, so great? Setting aside the natural feelings of those locals who were subject to British rule, for better and for worse, one cannot help but marvel at the remarkable discipline, planning, administrative organization the British brought to their empire. Any nation today would be well served to get one tenth that level of service from its own government.

And why would a book published in 1955 be interesting today? For one thing, history has a tendency to repeat itself, or to repeat versions of itself — things that happened in the past seem to happen all over again. If we who are living now can harness the lessons of the past, then we can avoid the mistakes of the past, too; or at least so goes the best thinking. Certainly one must know history in order to know what happened, and how to identify when the same forces are at work once again.

In order to understand where we are today, we must look at what decisions and resulting actions got us here, and why those choices were made (come to think of it, I recently read another similarly aged but highly useful book titled Why England Slept, written in the 1940s and 1950s, then authored and published in 1962 by some then-nobody named John F. Kennedy). The Uneven Road does an excellent job of explaining much of the Middle East and East Africa through one man’s colorful and risky exploits from a military and diplomatic hot seat along the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, and then into the Italian Alps. Judging by current events, little has changed in the former.

As the title implies, the author took an uneven road in his long life, following completely neither his traditional Scottish upbringing nor his adopted British devotion to Empire. As he says in so many ways throughout the book, Lord Belhaven is a lot like his forebears, individualistic, strong, self-driven men who admired authority and convention as much as they bucked them and tried to fit into them on their own terms. Or one might say, Lord Belhaven and his ancestors tried to make convention in their own image. As an American, to me this independence streak is a highly laudable trait, even if it did damage to the already impressive careers of Belhaven and his father and grandfather.

The author is both very open-minded for his time, gleefully throwing off class and religious barriers that today seem so unbelievably feudal, especially to Americans (and familiar to those Americans who enjoyed the Downton Abbey series) with our hodge-podge zero-caste-system, but which were quite dominant in his early years. He is also representative of some persistent silly views that are also peculiar to certain groups of people where he is from, even today. To me, an American, whether I agree or not, this is all part of being a natural, well-rounded human being, and a sign of being interesting. Everyone has prejudices and sharp-edged opinions, and everyone is entitled to them. No one is perfect, our author does not claim to be perfect, nor does he engage in the vacuous virtue signaling which so sharply defines today’s Western civilization. More to the point, neither you nor I are anywhere near perfect or nearly as exciting as Lord Belhaven, and only very few people you or I have met or ever will meet are going to be nearly as interesting as Lord Belhaven.

Writing as a soldier, administrator, diplomat, lonely husband and then divorcee, and amateur historian/ethnologist/archaeologist, Belhaven is a gentleman, and also a manly man. He is the old archetypical British\Scottish aristocrat patriot, both swashbuckling and under steely self control, a thing of the past which, my gosh, we now could use much more of in our own time. He is clearly a warrior, and an effective one at that, and yet much of his book is stories about how he was not such a great warrior, or how he was charged with establishing peace in lawless places through diplomacy, and yet relied upon deadly warfare.

As he reminds us, especially with the burning of the village of Jol Madram, diplomacy without the real threat and the occasional implementation of brutal violence is simply indecisive inaction, a weakness that inevitably invites more lawlessness or aggression. For Belhaven, there is no foolish, circular “conflict resolution” without resolving the conflict to concrete terms he likes and which work for the most people. Instead of getting “triggered” and fainting into a safe space when confronted with adversity, Belhaven the man of action responds by putting his finger on the trigger of his revolver and explaining just how things are going to get back to full function, or else. In a Western world today of namby pamby political correctness and feminized men, reading this book I could not help but think How refreshing! And also, Where the hell did our masculinity go?

The author’s voice is forthright, unafraid, honest, and though a few times I may disagree with his views, I keep thinking as the pages are turned, “Now here is a man I could respect and like!” Would that Western Civilization today had many more men like Alex Hamilton, aka Lord Belhaven.

Spanning the 1920s through World War II, and published toward the end of the British Empire, The Uneven Road is one more fascinating on-the-ground report in a line of the “Hell, I was there” genre of personal adventure histories written by British military and political officers across the British Empire, upon which the sun did not truly set until the 1960s. The Uneven Road is one of the last from the frontier, and in my experience it is one of the better written and certainly the most personally reflective. In some ways it is a companion piece (maybe even a necessity) to books written by or about others who traveled, explored, dug archaeological treasures, politicked, and fought in and around the Arab Peninsula, such as Lawrence, Philby, Ingrams, Jacobs, and others.

There are many, many examples of these personal field reports and histories from the 1790s through the 1960s. Some are famous, most are obscure, some are kind of boring, and many carry an overt agenda, and yet almost all are illuminating about life among the British Empire’s boots-on-the-ground administrators and soldiers, as well as the occasionally momentous political events of the day. The fact that these personal histories exist at all, and that they are often well written, says a lot about the high caliber of the British and Scots of that time, both the writers abroad and the readership waiting back home. The Uneven Road meets or exceeds all these standards.

While other major cultural “encounters” and confrontations have been largely or absolutely settled in the same time period, in key ways that are of great interest to the modern reader, this book is about East-meets-West, a contest that has only grown sharper and more defined a full hundred-plus years after it fully got under way, as described in these pages.

Britain: A Culture of Selfless Patriotic Duty

One need not read a book to hear or know about England’s long established culture of patriotic duty and self sacrifice for king and country, but reading this book will help the interested reader gain real appreciation for both the depth of feeling most Britons had then, and for the real personal cost it then meant later on in their lives. The unbelievable battlefield losses in World War One and WW II greatly changed England’s culture, resulting in a legacy of pacifism, fear of inevitable conflict, and self-defeat we see officially operating today.

Throughout the first half of his fine book, Belhaven off and on artfully weaves an analysis full of personal anecdotes of British military culture, including how wealthy aristocracy would often take a vow of poverty (as opposed to running a family business or a valuable property) to serve in the military, for the simple satisfaction of providing patriotic service to the nation. The following quote only touches on this, but it covers enough other turf to qualify for mention here:

“One Saturday, towards the end of our last term at Sandhurst, Tony Keogh and I were both excused [from] work because of minor injuries. Tony Keogh was a dour Wellingtonian, whose ambition was to give a lifetime’s service to Waziristan on the northwest frontier of India, a country which his father had been the first to survey.” (page 40)

Waziristan of the 1920s is today several different ‘stans, including parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan. It included then as it does now all of the intolerant, violent religious fanatics who still make it such a special place. From the 1880s through the 1940s, British troop losses there were big. Can you imagine being the first person to scientifically survey a significant portion of the planet, this very rugged, remote place specifically, surrounded by such danger? And then bear a son who simply wants to pick right up where you left off? Such was the tough, brave stuff the British were made of, once.

<sigh>

And it was that same patriotic fervor and absolute selfless commitment that made such brave soldiers for World War I and then World War II, and then resulted in the pacifism of modern Britain, when few men returned home:

“Toll for the brave!” that most perfect of slow marches – how often had we marched to its slow, sharp rhythm. When I hear the tune now I can see, as I saw then, the high, shining fence of bayonets, the straight, erect lines moving forward with irresistible menace and force, the very symbol and image of war. And all with its glint of youth unafraid, unconquerable. Toll for the brave indeed; few who marched that day have pottered on as I have done for fifty years.” (Page 40)

<sigh>

His description of his surprise at winning the Sword of Honour at Sandhurst is both funny, and then sad, as his stiff-upper-lip military father refuses to acknowledge it until two years afterward, and only then sarcastically. That sword becomes a snapshot of his challenged relationship with his father and also a symbol of British culture.

Report from the Frontier: “It was impossible to be bored in Aden”

If India and Africa provided the greatest quantity of opportunity and adventure (the British defeat of France’s fleet at the Nile, the ‘Mountains of the Moon’ search by naturalist-explorers Burton and Speke for the source of the Nile, the Mahdi, the Zulu Wars, Islandlwana, Rorke’s Drift, the Boer Wars, and so on) for these far-flung representatives of Her Majesty’s Service, it was the Near East and Middle East that created the most vivid and gripping images consumed widely by the public, even today.

Think of “Lawrence of Arabia” and all the thrilling weight that phrase still carries a hundred years later. And so just a decade-plus after a charismatic young Brit, T.E. Lawrence, led the Arab revolt against Ottoman Turk rule throughout the Near and Middle East, it is primarily on and around the Arabian Peninsula that Lord Belhaven’s book takes us. It is an often militarized and occasionally one-man-army journey by foot, camel, horse, donkey, bi-plane, and boats of various type and size, including some pleasure craft of his own construction.

Based in Aden and sallying forth through abandoned ruins from hidden, unknown, lost civilizations to high mountain forts inhabited by fierce tribes, Belhaven fearlessly and luckily does his best to bring order to the fractured tribal chaos of the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, what today is known as Yemen and known then as the British Protectorate of Aden. Like most Brits of his time, Belhaven was an Arabist, an Arabophile who simply looked past the stark differences of Mohammedanism compared to his own culture of gentle mercy and forgiveness, stricken as he so clearly was by exotic Arab ways. His gunfights, in which he was sometimes greatly outnumbered, the aerial bombings, and his knife-edge nose-to-nose confrontations with cutthroat highway gangs and treacherous tribes are the stuff of legend; his fishing and hunting trips during working hours are not, though he does describe them in obvious joy and often at his own expense.

Though in a serious tone Belhaven opens up about his family life in the first third of the book, in the rest he makes it clear that he knew how to have fun and push British foreign office sensibilities beyond their traditional staid demeanor.

Belhaven gets extra credit for a dry wit and self-deprecating humor applied from several miles up. He does not take himself too seriously, or even seriously at all, at times, even as the bullets are flying and his life hangs by a thread. This bon vivant tone heartily leavens the serious life-and-death situations he describes, including shooting himself in the foot in the heat of battle, and nearly shooting his Somali hunting guide who chases a large leopard out of a cave and into Belhaven’s face, not to mention his rear line and front line experiences in World War Two.

One of the artifacts of time and place is the author’s fascination with genetics, a hot (and also destructive) topic of that era. Repeatedly marveling at the “pure” inbreeding of certain tribes along the southern Arabian Peninsula, the author relied upon simplistic, romantic, and plainly incorrect notions of genetics. But this is to be chalked up to the general and long lasting British awe and love for the colorfully fierce Arab nomads of that region. Whatever they did, no matter how backwards or weird, was very cool. Who can blame him for thinking thus? Were you or I to live out there today, we would find it just as alien and compelling as he did, and it would all be just as cool now as then.

Insights into his own family struggles with intimacy and finances, and the perhaps unrealistic lifestyle expectations accompanying title, are illuminating for those wondering how the famous British aristocracy slowly crumbled from the inside and out.

When it comes to archaeology, what is not mentioned is louder than what he might have written. Lord Belhaven apparently had an eye for long lost antiquities easily unearthed with the toe of a boot in the loose sand of some long lost civilization in the middle of the blistering desert. In a tempestuous sea of worldwide archaeological looting by British nobles, scientists and adventurers, Belhaven’s personal interest in a few old broken, abandoned things lying in the dirt was strangely singled out for criticism by a couple of bespectacled Peabody types in imperial administration back home. Belhaven makes no mention of any of this in his book, and maintains his focus on big picture civilizational development. As he should, in the tradition of the fighting naturalist-archaeologist hero; a kind of Indiana Jones.

Detailed references to carved alabaster amid the sands, and marble ruins, lost cities, dams, water works also occasionally appearing and then disappearing amidst the shifting sand dunes add an element of authentic mystery that is harnessed in the Indiana Jones and The Mummy movies. Except that Belhaven was actually there, and saw and explored those ancient mysteries with his own eyes.

Will a couple of “Aw, shucks” ruin all the “Atta Boys” in this book?

Though he does not explicitly set out to do so, the author’s plainly spoken recollections invite the reader to share the author’s unspoken pangs of loss over decreasing British influence and culture.

In 1955 the author was in good company, with his views on race (a word he uses many times with several different meanings), skin color, religion, and social class, even as he was clearly departing from those long-held views. Bigotry and class snobbery were then becoming a thing of the distant past, a change which Belhaven mostly embraces and in many ways led in his own “black sheep” personal way. Those anachronisms particular to that time period he retains were either common figures of speech, cultural crutches, or concrete functions of Caucasian minority survival in otherwise hostile foreign places.

We today may not agree with him or his use of some words, but he usually explains himself well, and so we can often understand his thinking. Understand is the key word here, and it does not mean or infer acceptance or approval. And if the reader wonders why I, myself, am insufficient in my condemnations of the author’s few lapses, may I suggest one consider the word “tolerance,” or the phrase “open minded,” or that almost extinct word “understand.” In other words, that was then, this is now, these are different times than then, and once again, everyone has opinions and views that others find “offensive” or uncomfortable. Get over it, get over yourself, learn to tolerate differences in opinion, and move on. I did, and you can, too.

In an educated and open society such as ours, everyone is entitled to an opinion, even a wrong opinion, and even a bad one. God knows, today’s self-righteous book-burning censors falsely accusing everyone else of political heresy and racism have plenty of bad and wrong opinions themselves. In the past, people have been and should continue to be able to disagree with one another without taking silly offense at the simplest of differences, and then retreating to corners and brandishing the war colors. Goodness gracious, people, put away the guillotines! Give people some space to be wrong, or to explain why they thought they were right. And that maturity is what a reader must bring with them to get the most on this trip through time.

For example, in a book full of many humorous and comical stories, anecdotes and quick turns of phrases, there are a couple references to race and genetics, captured so perfectly in The Uneven Road, that really shine a light onto the important evolutionary changes of thinking and attitude about race and skin color happening in the pivotal 1950s. Recall that Belhaven is a born aristocrat:

“I found the whole subject of breeding, as it was accounted in our curious society, absurd; if a man married the crossing-sweeper’s daughter, no one bothered to find out about her breeding; her father’s trade was enough to condemn the match. When it was discovered that he was a rich Jew, who swept crossings through eccentricity, opposition could be relaxed, particularly if he kept race-horses and was a member of the Carlton.” (P. 29)

One page later Belhaven hilariously describes how his Eton school class failed a basic introductory genetics course on mice, with the best and wildly cheered answer to the teacher’s question being a boy’s half-assertion-half-question that inbreeding causes parents to eat their young.

Fast forward sixteen years and Belhaven, now working as a British Political Agent in the Arabian Peninsula, writes: “I have sat in their gathering of Princes, in their Chief’s lamp-lit reception-room and watched them, their skins shining like polished gun metal in war-paint of oil and indigo, a dull sheen of gold and silver in their great daggers, curved with the curve of the moon; the remnant of a great nation indeed, virile, unconquered by arms or by time, handsome and courageous. And marvelling, I have remembered that these men among whom I sat married always, by long custom amounting almost to law, among their own family; so through the millennia they have achieved an extraordinary purity of breeding…for a period of five thousand years…” (P. 86, emphasis added)

And so, as much as Belhaven mocked his fellow students on their failure to grasp the essentials of healthy, necessary genetic diversity among mice and humans, he then later includes himself in their unfortunate company by endorsing the worst sort of human inbreeding, still going on even today in the Arabian Peninsula. This is the intellectual price one might pay for getting emotionally involved with something, as did Belhaven and all of his fellow Arabists. However, it remains fact that none in that time could have remotely foreseen that a surprisingly large number of parents across the Middle East would today encourage their own children to engage in suicide bombings and attacks. Talk about parents eating their young…

Just coming out of the real, actual Lawrence of Arabia time, an amazing time of high military and political adventure, and his living and working in that exact location with many of the same people, Belhaven’s near infatuation with all things Arab and Islam were then and are now understandable. His views on the Middle East were widely shared among his fellow Brits and Scots at that time. Even today many British still cling to detached, romantic notions of Arabia and Sharia-compliant beheadings and stonings, though having now painfully absorbed nearly half of the Arab world into London and having watched the other half wage sadistic war amongst themselves at home, and against Western Civilization abroad, has been shifting those old romantic notions into some other cold, hard, realizations.

Similarly, his views on Jews and Judaism range from the ground-breaking class acceptance (done with excellent humor at the expense of his fellow Brits; see above) to the old traditional British snobby disdain. He was only a little less tough on the Church of England. One must wonder what Belhaven would have written had he lived to see most American Jews and the Church of England and the current Pope all almost wholeheartedly embrace Marxism and anti-Western anarchy. If there is a resurrection of the dead, I want to be right beside Belhaven, so I can be the first to hear his colorful, insightful reaction to these unfortunate, really unbelievable facts.

One thing Belhaven did not live to see was the now-modern state of Israel, the then-nascent version of which he refuses to name in his book, but which he negatively alludes to several times. This is the old fashioned British Arabist coming through. Of the Jews of Yemen he has a brief but historically important and also humorous first hand encounter and report; but he then fails to mention their subsequent unjust inclusion among the nearly one million innocent Jewish refugees ethnically cleansed by his cool Arab friends from their ancient, very pre-Islamic communities across North Africa, the Near East, and the Middle East.

“So we came near to the end of our stay in Sa’na. Champion [Sir Reginald Champion, then Civil Secretary to Aden and later its Governor] and I called on the head of the large Jewish community in the city. Although considered by the Arabs to be an inferior race, the Jews of the Yemen were well treated by the Imam [Imam Yehia, a Shia leader who later lost the Arabian Peninsula to the Wahhabi al-Saud family, and whose spiritual descendants today are the once-again rebellious Hauthis]…Now there are no Jews left, they have all gone to Palestine, a Promised Land without either the milk of human kindness or the honey of their expectations…” (P. 104)

Hello, Lord Belhaven, reality is calling now, just as it did in 1955. The Yemenite Jews did not just casually get up and leave their homes in Yemen of 2,000 years for Israel out of a desire for better falafel or flush toilets; they were universally axe murdered and driven out of their homes by the same Muslims you so admire, the lucky survivors arriving in Israel with the shirts on their backs, their family homes and businesses stolen and occupied, their bank accounts looted, their personal property removed by force, like all the other Jews from every other Arab country at the same time. So why Belhaven ignores these facts to get in some shots on Israel is, again, likely a question of the impact of that romantic infatuation with remote alien cultures. Were he alive today, he would probably be a Christian Zionist like another famous and contemporaneous British Arabist, Col. Meinertzhagen (who when introduced in private to Adolf Hitler responded to the perfunctory ‘Heil Hitler‘ with his own ‘Heil Meinertzhagen‘).

Did Belhaven write some occasionally harsh stuff? Maybe so, certainly by today’s standards. But so what. Get over it. On balance, this book is 99.999% fascinating, illuminating, educational, and important history. Why judge and then dismiss the entire work based on a couple anachronisms from his own day?

As briefly mentioned above, one of the big challenges our younger generations are failing at is their tendency to immediately be offended by, and then harshly judge and dismiss, older generations by applying current standards. Instead of trying to understand how the previous generations thought, and why they fought way back when. Surely there must have been compelling reasons for the many momentous decisions that were made and then chiseled into stone or cast in bronze. Not everything back then is “racist,” which has become as hollow a crutch word as can be found. As old statues, symbols from important self-inflicted internal wars across America, are pulled down by screaming, infantile, anti-history mobs, one cannot help but wonder if the screamers will ever be interested in why the statue was erected in the first place. Or do they aim to simply re-write history (irrespective of the actual facts, causes and effects) to suit whatever political purpose suits them at some future time? I would rather have Belhaven’s honest accounting than a dishonest re-writing of who we are and how we got here.

In sum, whatever “Aw, shucks” Belhaven may have earned in a few spots here or there, they are far outweighed by the many “Atta Boys” he racks up over and over throughout this excellent book. For those younger folks who are actually and truly interested in understanding history, and how people’s views on race, religion, and income\ social standing changed over time in Britain and America, and how the Arabian Peninsula yet remains completely unchanged, The Uneven Road is a refreshingly honest and educational Exhibit A at the crucial time of the post-war 1950s.

Obscurity often means fascinating

Many years ago, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when it was an actual newspaper that reported much actual news, instead of having the entire paper be one editorial after another masquerading as news, which it does today, the New York Times published a series of articles based on the simple methodology of having a news reporter (another extinct species the younger generations have never seen) open the New York City phone book (‘And what, too, is that?’ the younger generations ask) and randomly place his or her finger on the page. This was done ten times over the course of a bit over a year, as I recall. Whoever’s name was there over the finger nail got a call from the finger’s news reporter, who then did a detailed report on that person’s life. As the subsequent reports showed, despite living almost entirely quietly and privately in the big anonymous city, each and every one of those randomly selected people had nonetheless led a fascinating and often deeply compelling life.

And so, here now we have similarly plucked out of historical obscurity a book long out of print and probably originally of interest to few beyond aging British soldiers and Foreign Service dignitaries. Yes, here in Lord Belhaven we have a man whom very few have heard of, and as he is an aristocrat he is presently out of favor for having violated some social construct or…thing, even though he was a reflective, self-deprecating, risk taking and self-sacrificing humble public servant who enjoyed breaking with his own social norms and elevating many downtrodden. His life was more than fascinating, it was bigger than life, as we say. It was certainly bigger than my life or anyone else’s life I know of, and I know some pretty adventurous people in military and law enforcement, as well as international hunters. And today outside of Britain and America’s special forces operating abroad, very few public officials do anything close to what Belhaven did. And given the opportunity, few today would take it. Pity.

It was people like Lord Belhaven who put the “great” in Great Britain. Given how far and wide Hollywood looks for true-to-life stories, why no one has done a movie based on this book or on Belhaven’s life is one of those mysteries that highlights how shallow Hollywood is. Because it is true that Indiana Jones was mere Hollywood fiction, whereas Lord Belhaven was for real.

Time for a new Dune movie

The 1965 book Dune was to a great extent the basis of most futuristic science fiction books and movies that followed. Star Wars is based on Dune, even beginning on a desert planet where the hero, Luke Skywalker, has been tested and hardened into a ready warrior by the harsh landscape around him, like the Fremen of Dune’s desert planet Arrakis.

“Dune” author Frank Herbert was an eclectic guy, a deep and creative thinker. One might say he was unusual, even by modern terms.

He was against racism but believed in the importance of human genetic improvement through select breeding. Focusing on the importance of tribalism, Herbert nonetheless elevated the self-reliant individual as the highest achievement a person could aim and hope for.

He was for the concretely purposeful use of mind-expanding drugs, such as religious experiences, saw warfare and killing as hardly noticeable inevitabilities in a well-ordered human universe, believed in God and the power of prayer, supported the ongoing evolution of technology, but then elevated the supremacy of human evolution and the human spirit, including personal fighting skills, over that same technology.

If his amalgamation of nearly all current religions on Planet Earth into one or two future strands of religious thought is any indication, Herbert is suggesting that all religions pretty much point us in the same direction, though some are scarier than others.

Herbert was firmly against artificial intelligence and the delegation of human decision making to machines. In Dune, it is the ‘Butlerian Jihad’ that wipes out most computers and all AI, leaving only those computers that could perform the basic elementary functions in lieu of humans, after a close call where AI and its robots nearly took out all humans. On this subject, it could be said that Herbert was prescient and, like many other sci-fi writers, ahead of his time. Even now we childishly rush into AI as if it is just a silly game, when in fact it could quickly kill every human and every other life form on Planet Earth.

In 1984 director David Lynch produced a pretty good movie that captured a lot of the book Dune. No small feat, as most great books result in terrible movies. The David Lynch movie was good because it embraced the book and did not try to dance around it. Its acting was mostly excellent, and some of the scenes are perfectly gritty. But in other ways the 1984 movie is very weak. Its special effects are almost sad, even by the standards of that time. Very 1950s.

A miniseries was attempted years later, and many Dune devotees believed it was a failure in every way. Lacking even the punch of the 1984 movie, it certainly was not what people had hoped for or imagined.

We need a new, updated Dune movie. No, we demand one. A Dune movie that is absolutely true to the book, that has the same quality actors as the 1984 version, and which has updated technology, sets, and special effects. It will have to be long, three hours, to capture the most important scenes and subtle nuances that make the Dune story so powerful.

C’mon, Hollywood, do something good for once. Give us a new Dune movie that is worthy of the name and the book.

Book Review: Lyman Cast Bullet Handbook 4th Edition, Data Rifle Handgun Calibers Molds

My apologies up front to the authors, but this is a disappointing book, sorry to say. The good news is there is an obvious need for a fifth edition that addresses the deficiencies.

Despite its title, this is not a handbook about cast bullets.

It is first and foremost a handbook about Lyman reloading products.

Second, it is a long listing of popular pistol and rifle round dimensions, as cast in an undefined lead alloy (probably linotype alloy, judging by that alloy’s popularity in the book).

Beyond that this book is a random assortment of poorly structured and brief, incomplete descriptions of elements of lead bullet casting. I hate to do this, but here are some specific criticisms:

1) It has few European cartridges and no (British, German, Swedish, Austrian, French) Black Powder Express calibers. This is a gaping hole in any case, but especially in light of the tremendous upsurge in interest in BPE rifles.

2) Nothing about paper patching, which has seen a resurgence because it works very well, and a lot of, if not most 1870s-1890s black powder guns in America and Europe shot paper patch cast lead bullets.

3) Unbelievably lame and incomplete lead alloy list, missing critical and most practical field-use characteristics for each alloy. When I purchased this book new, I was expecting some discussion of the relative merits of pure lead, 50:1, 40:1, 30:1, 20:1, 16:1, and 12:1 lead alloys, and perhaps a discussion of their different purposes i.e. thin skinned or thick skinned game, at what ranges, their hardness and weight out of the same mould relative to one another, plain base vs. gas check, etc. There are some lead alloys that are predominant or most popular (40:1, 20:1, 16:1) among reloaders, because they are very practical, cheap, easy to make, easy to cast. There is zero recognition of this simple fact here. Instead the authors treat us to their own narrow interest in very hard Linotype alloy, which of course has its use on the toughest big game, but my gosh, gentlemen, there is a whole world out there of LEAD.

4) Lots of wasted pages and space on scientific nonsense about melting lead. I have a graduate degree in statistics and economics, which indicates I can think hard and well when I have to, and I have a lot of interest in the subject of casting lead bullets (and sinkers, and jigs). And yet, I still fell asleep after the first paragraph about the physics of melting lead. This section is unreadable, as well as pointless and useless for practical lead casters.

5) Very little is written about mould types or materials i.e. relative merits of bronze vs. brass vs. iron vs. steel, or should we use the antique moulds or have new ones made, or how to care for moulds, single block vs. split block, etc. This is a huge subject as more and more mould makers have come on line all over America and Canada to meet the strong demand for custom bullet moulds, each offering their own preference of mould material.

6) Nothing about the Ideal tool, which is also becoming popular again, i.e. how do you properly store and travel with your paper patched bullets, so you can load them on-site?

7) It is pre-Internet, although an Appendix is roughly tacked on promoting certain Lyman wares and suppliers available on the Web.

8) Finally, adding insult to injury, the cover contradicts the text. The primary author describes how he ladle – pours with the spout right in the mould pour-hole. Yet the cover shows a dramatic looking stream of molten lead leaving the ladle and landing in the mould some distance below. And that right there summed it up for me: The cover shows one thing, the text describes another. I am frustrated and disappointed by this book, and so I rank it at the very bottom of reloading books. And yes, I have been shooting black powder since I was a kid, so I know of which I speak. Frankly, you can get much better, more useful, more accurate, more up-to-date information from the guys at various web pages (castboolits, nitro etc.) than you will get from this book.

How sad this is. But as noted, if the authors address these concerns, the next edition should be truly a bible on cast bullets.

Google, Facebook, COSTCO – each trying to suppress your free speech

If you think that social media sources like Google and Facebook treat everyone equally, you are wrong.

If you think that COSTCO treats everyone equally, you are wrong.

All three have been documented in recent days to be in an aggressive war against your free speech opportunities, and against your ability to access information that the owners (of Google, Facebook, and COSTCO) do not like.

The owners of all three institutions are liberals.

Liberalism went from a demand for fairness to an overarching totalitarianism in a few short decades. While many people say now and said back then that the socialist and communist roots of liberalism indicated that liberals were never interested in fairness, being open-minded, or tolerant, I grew up surrounded by liberals, and it was not until the last decade that I witnessed what looked to me like a transformation. They went from representing opposing views to crushing opposing views, terminating dissent, as soon as they had the opportunity.

For example, the gentle “peace”-loving pacifists <ahem> were on the war path at Chautauqua Institution, a place long known for providing a platform for different ideas and views. Suddenly authors like Andrew Bostom were shut out of week-long discussions where Islamic terrorists had the stage, as though they could not possibly be balanced by another opposing view. And it then dawned on me and many others that liberalism is just one more tyrannical, evil, cruel, divisive, phony movement designed to create winners and losers by any artificial means necessary.

Like all totalitarian movements, liberalism must be opposed in the name of freedom. Let people make up their own minds.

If you want to see how liberals have been shutting down your free speech opportunities this past week, visit these links:

http://www.dineshdsouza.com/news/wnd-costco-removing-dsouzas-america-shelves/

And simply use BING to search for examples of how Facebook has artificially shut down and hindered conservative Facebook pages, including our own Josh First for PA Senate.

UPDATE: How could we forget to mention that Google removed the Gates of Vienna blog without any notice to the owners, thereby violating the very terms of service that Google themselves had required. The Gates of Vienna blog is a well-known source for history and updates from around the world. But the Left, ah, the Left, they cannot tolerate dissent. So, Google, run by liberals, tried to destroy the blog. But it survived. Use BING to look up the story.